Mobile Robot Control 2024 Ultron:Final Report

(Group deadline: 21:00 28 June)

Introduction

High-Level System Description

(Yidan)

System Architecture

State Flow

(Liz)

Data Flow

The data flow diagram illustrates the interactions between input sources, processing modules, and output commands for the robots. There are three major input sources: the laser and odometry come from the robot sensors, and the map is uploaded by the user. The map provides the existing representation of the restaurant environment, including the table positions and order information. The laser detects obstacles in the environment. The odometry supplies information regarding the robot’s position and velocity.

The Localization module first receives the data from all three inputs to determine the robot's position relative to the map. Over time, the robot's theoretical and actual positions will eventually diverge because of accumulated errors from odometry conversions between theoretical and real movement. Therefore, it’s fundamental to ensure that the robot knows its exact position within the environment during its movement for accurate navigation. The position is then forward to both Global Navigation and Local Navigation modules.

Global Navigation uses the map to plan an optimal path from the robot’s current position to the destination through the combination of PRM and A* algorithms and updates the current target point for Local Navigation. Local Navigation uses the current position, the target point, and the laser data to adjust the robot's path dynamically, avoiding obstacles and navigating through tight spaces. It provides control commands for linear and angle velocity to guide the robot's motion.

The Stuck Detection module handles abnormal status during the local navigation. If the robot is within 0.2 meters of an obstacle according to laser data or cannot find a path to reach its target points due to an unknown static obstacle or being stuck in a local minimum, the stuck detection module is triggered. It stopped the robot and initiated a path re-planning through the Global Navigation module.

The process involves a continuous feedback loop, constantly monitoring and adjusting the robot's movements based on inputs and environments to ensure safe and efficient navigation towards its destination.

System components

Initialization

(Lu)

Localization

(Aori)

(Yidan, Hao)

Probabilistic Roadmaps Methods

A* search algorithm

The A* algorithm we implemented has two working modes: it can build a planner by obtaining connected nodes from the grid information or the PRM algorithm. Since the grid information of the map is not given in the final challenge, we use the sampling nodes and connections between nodes given by the PRM algorithm.

The idea of building a path planner based on PRM is as follows:

1. Read the coordinates of the start and end points from the configuration file. If the configuration file contains start and goal parts, overwrite the default values.

2. Get the number of nodes and connections in PRM and create a new node list and connection relationship container. Copy the node and connection information in PRM to the new node list and connection relationship container. Node ID starts from 2, and 0 and 1 will be used for the start and end points.

3. Create the start and end nodes and add them to the node list. Check the validity of the connection between the start and end points and the existing nodes, and establish a connection relationship.

4. Planner creation and initialization, set the initial cost [math]\displaystyle{ g }[/math] of each node to infinity, the heuristic cost [math]\displaystyle{ h }[/math] to the Euclidean distance from the node to the goal node, and the total cost to [math]\displaystyle{ g + h }[/math]. Create an open list to store the nodes to be processed, initially including the start node. Create another closed list to store the processed nodes.

5. Start path planning and select the node with the smallest total cost value in the open list for expansion. If the node is the target node, the path is found and the loop ends. Otherwise, add the neighbor nodes of the current node to the open list and update their initial cost value, total cost value and parent node. Remove the current node from the open list and add it to the closed list.

6. Starting from the target node, trace back to the parent node and generate a path.

7. The return value of the planner contains the node list, connection relationship, start and end nodes.In the main program, the A* algorithm is called before the while loop and after the PRM call. By adding reasonable conditional judgments and printing content, we ensure that the nodes and connection content can be read from the generated PRM image results. In order to deal with the situation where the node connection generated by a certain call to the PRM algorithm is unreasonable due to improper PRM parameters and the randomness of PRM, and then A* has no solution output, we set the corresponding judgment conditions. In this case, PRM and A* are called again. Ensure that there is an executable node list in the final pass to the local navigator.

Dynamic Window Approach

Given a target point by global navigation algorithm and positions of obstacle by laser sensor, local navigation aims to calculate an available path to avoid collision with the obstacles as well as to move towards the target point. The outputs of all local navigation algorithms shown in lectures are directly the desired velocities [math]\displaystyle{ (v, \omega) }[/math] ([math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] is linear and [math]\displaystyle{ \omega }[/math] is angular velocity) of the robot. There is no need to perform a path following task.

In exercising, we implemented both Artificial Potential Filed (APF) Algorithm and Dynamic Window Approach (DWA). At first, we chose APF as our local navigation algorithm because of its robustness and simplicity. However, during the test we found that APF is not ideal for vertex handling and the robot will oscillate when driving through a corridor, whereas DWA can generate smoother trajectories and shows great potential for dealing with complex scenarios. And DWA is designed to deal with the constraints imposed by limited velocities and accelerations, because it is derived from the motion dynamics of the mobile robot. This is well suited to the realities of Hero. Moreover, DWA contains the idea of optimal control, which can improve the efficiency of the robot. Thus, we switched to DWA.

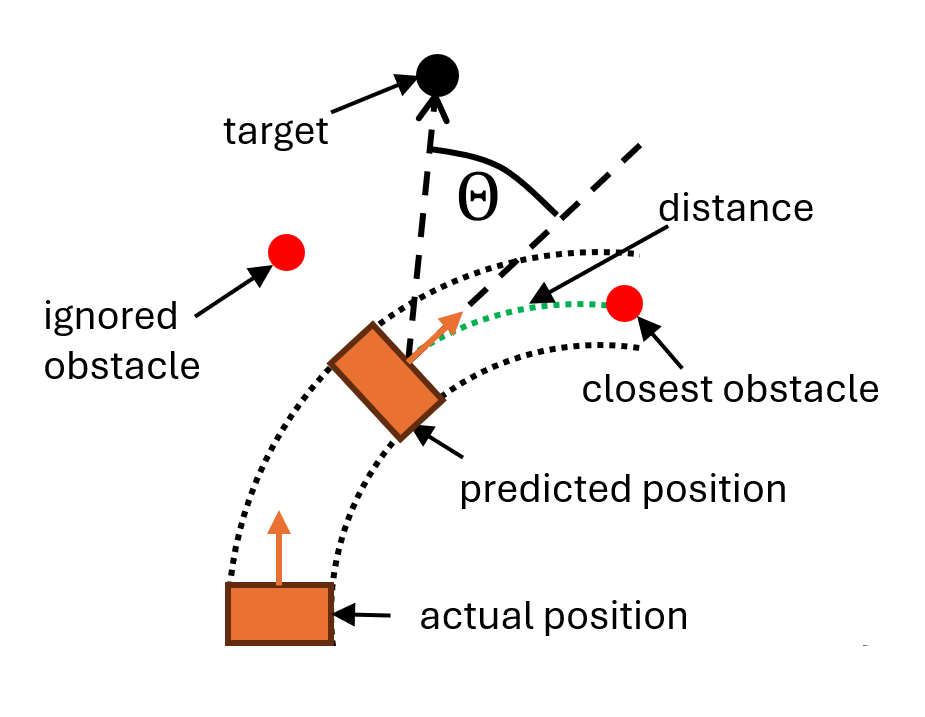

DWA performs reactive collision avoidance. When computing the next moving command, DWA considers only a short time interval, within which the robot's velocities [math]\displaystyle{ (v, \omega) }[/math] are considered to be constants. The algorithm will evaluate the results of all possible velocities and select the optimal one. Instead of using the simplified version introduced in lectures, we use the original version of this algorithm proposed by D. Fox, etc[1]. The main difference is that the original algorithm uses a more refined geometric model when calculating the distance between the obstacle and the predicted trajectory, taking both the trajectory and the robot size into account. As shown in figure on the right, the obstacles that are not on the trajectory will be ignored. And by including a safety margin, we can control the minimum distance between obstacles and Hero.

The set of all possible velocities [math]\displaystyle{ V_r }[/math] is called the search space. It is the intersection of three sets: [math]\displaystyle{ V_r = V_s\cap V_a\cap V_d }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ V_s }[/math] is the set of velocities that are limited by robot's dynamics, [math]\displaystyle{ V_a }[/math] is the set of velocities with which the robot can stop before reaching the closest obstacle and [math]\displaystyle{ V_d }[/math] is the set of velocities constrained by current velocities and acceleration.

These three sets are defined as:

[math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \begin{matrix} V_s =&\left\{v,\omega |v\in[v_{min},v_{max}]\wedge \omega\in[\omega_{min},\omega_{max}] \right\}\\ V_a =&\left \{v,\omega |v\le \sqrt{2d(v,\omega )\dot{v}_b } \wedge \omega \le \sqrt{2d(v,\omega )\dot{\omega }_b} \right \}\\ V_d =&\left \{v,\omega |v\in [v_{a}-\dot{v}\Delta t,v_{a}+\dot{v}\Delta t] \wedge \omega \in [\omega_{a}-\dot{\omega}\Delta t,\omega_{a}+\dot{\omega}\Delta t] \right \} \end{matrix} \end{align} }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \dot{v}_b }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \dot{\omega }_b }[/math] are maximum deceleration values and [math]\displaystyle{ d(v,\omega) }[/math] is the distance to the closest object; [math]\displaystyle{ v_a }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \omega_a }[/math] are actual velocities and [math]\displaystyle{ \dot{v} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \dot{\omega} }[/math] are maximum acceleration values.

[math]\displaystyle{ V_s }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ V_d }[/math] ensure that the selected reference velocities is consistent with the physical limitations of the robot. And [math]\displaystyle{ V_a }[/math] ensures that the robot does not collide, because the distance item of velocities that lead to collision will be zero, making these velocities unavailable.

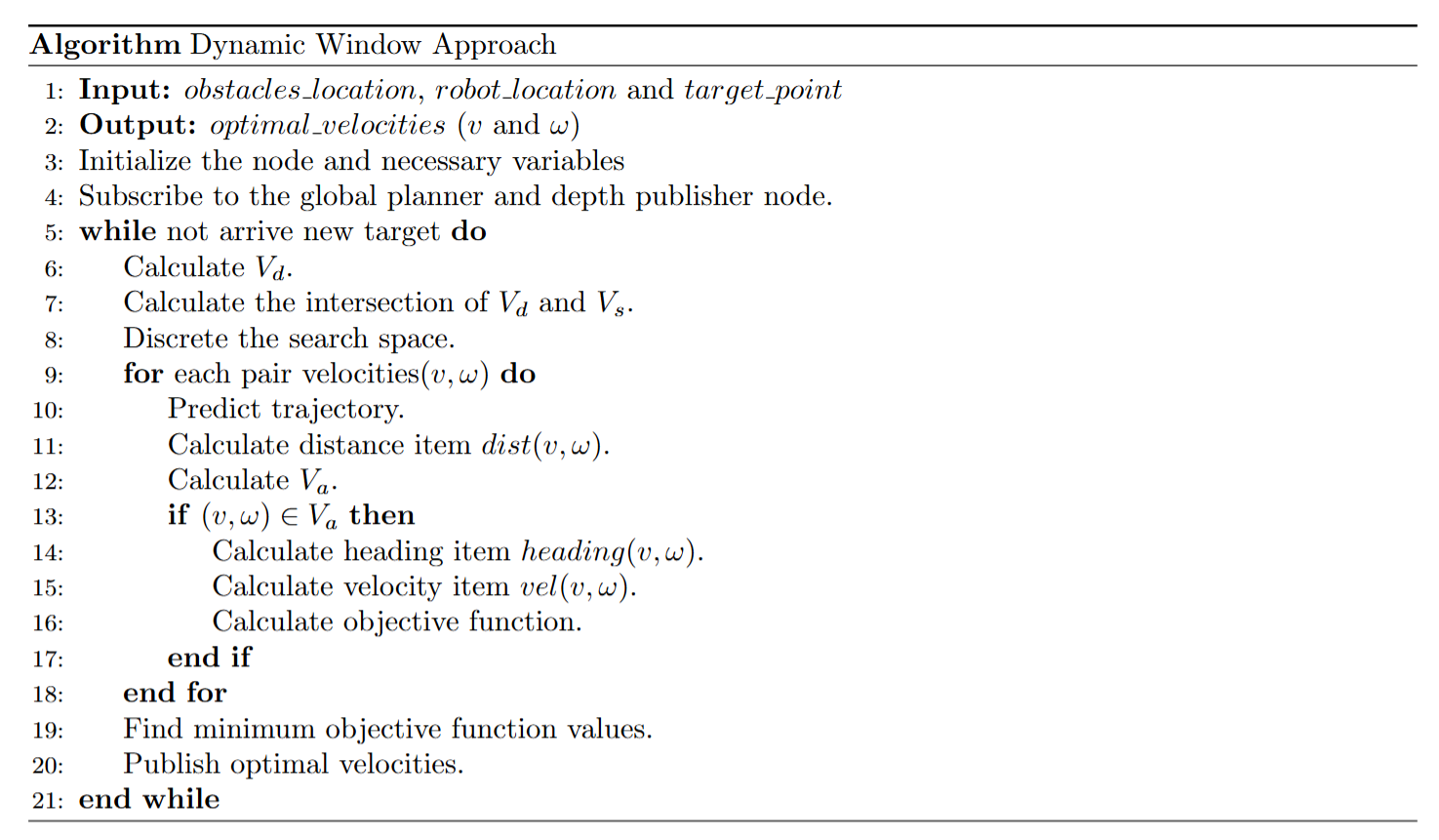

Implementation in C++

As shown in the figure on the right, the DWA is basically a discrete search to maximize the reward function. Considering the large number of parameters of DWA, we implement DWA as a class in C++ and make those parameters as class-scope private constants. There are two advantages to such an implementation.

Firstly, with the limitation of class scope and constant private variables, these parameters will not be accessible to other code, which guarantees these parameters will not be modified by other code and helps to improve code clarity.

Secondly, packaging all the parameters of DWA in a single class helps to improve the portability of the code. One can easily use this code by including a head file. And if we want to change these parameters only, we can simply re-compiler this part solely and then link it with others, instead of re-building the whole project. The reason we didn't use a file (such as JSON or XML) to configure these parameters is that we want the compiler to perform compile-time constants optimization, as these parameters should be known constant in the final challenge.

Parameter Tuning

Simulation Results

Test on Hero

Interaction

When the robot reaches the target table location, it turns in the direction of the table and performs voice interaction. This function is realized as follows. 1.Checking if the Robot is Near the Table 2.Updating the Flag and Outputting Information 3.Calculating the Target Angle 4.Rotating the Robot

Final Challenge Results

Results Analysis

(Hao)

Until the final challenge, we did not successfully integrate the localization code, so we used the backup code in the final challenge. The code only includes the local navigator of DWA and the global navigator using PRM and A*. And added the following functions: update the robot position information according to the Odometry data, determine whether it has reached the table position based on the position information, turn on the spot after reaching the table, make the robot face the table, and give a clear arrival prompt. Then return to the original direction and use the local navigator to go to the next table. Repeat the above steps for any table until you reach the end of the node list given by the global navigation.

In the first round of robot testing, we did not successfully reach the first table because the actual starting position of the robot did not match the map position specified in the config file. The actual position was to the left of the ideal specified position, which caused the first table to cross the robot's global navigation trajectory. It encountered obstacle avoidance behavior generated by local navigation at the first table, which also prevented it from getting close to the table position we specified to determine the location. The judgment condition for the table position is a one-time flag and a real-time calculation of the Euclidean distance between the current position and the specified table position. Therefore, the wrong robot starting position made the subsequent path and table position judgment invalid. The robot always believed that it had not reached one of the node lists, so it tried to return by turning at a large angle and reach the coordinate position corresponding to that node. However, since the node coordinates are in the actual table position, the robot cannot reach them, so the first attempt was not successful. The video can be checked in

In the second attempt, we adjusted the robot's starting position and gave instructions to control movement during normal program operation, but the robot did not move. We were later told by the TA that this was due to an unknown robot hardware failure. Therefore, we were given a third attempt.

In the third attempt, after rigorous distance measurement, we used the relatively correct actual robot starting coordinate position. After a period of straight tracking, we arrived near table0. When the Euclidean distance condition and the one-time flag judgment condition were met at the same time, the "arrival at the table" program was entered. The robot stopped on the spot and rotated 90 degrees to the left so that the robot faced the dining table. The robot gave an obvious arrival prompt sentence "I arrived at table zero", then stopped for 5 seconds, rotated 90 degrees to the right on the spot, and the program returned to the normal tracking state. The robot went to table 1. It was not necessary to reach table1 in the final challenge, so we blocked the flag for table1. There is also a chair as an obstacle in front of table1. The obstacle partially passes through the node list generated by global navigation. Here the DWA algorithm takes effect and helps the robot avoid the chair. The robot then continues to go to table 2。

Future Improvement

(Nan)

- ↑ D. Fox, W. Burgard and S. Thrun, "The dynamic window approach to collision avoidance," in IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 23-33, March 1997, doi: 10.1109/100.580977. keywords: {Collision avoidance;Mobile robots;Robot sensing systems;Orbital robotics;Robotics and automation;Motion control;Humans;Robot control;Motion planning;Acceleration},