PRE2018 4 Group9

Group members

| Member | ID number |

|---|---|

| Rob de Mooij | 1017797 |

| Ilja van Oort | 1001232 |

| Sara Tjon | 1247050 |

| Thomas Pilaet | 0999458 |

| Joris Zandeberge | 1231962 |

Problem statement

The problem of space debris is becoming bigger and bigger. This debris consists of used rocket-stages, non-operational satellites, parts that were created through collisions and anti-satellite tests. Since the 70s this problem has been getting increasing attention and big space associations like NASA and the ESA are constantly tracking this debris and preventing the creation of more. That is why most newly built satellites have built-in procedures that make sure the satellites de-orbit when they become out of order. However there has already been put a lot of material into orbit which is still creating risks for operational satellites and even more importantly the International Space Station (ISS). The ISS is constantly assessing the risks of space debris hitting it. From ground, debris down to 10 centimeter in diameter can be tracked and therefore also avoided by the ISS. The ISS’s crucial parts are protected by a dual layer wall that shield them from debris smaller than a 1 cm diameter. The biggest danger for the ISS are therefore space-debris with a diameter apr. between 1 and 10 centimeter, to which the ISS currently cannot defend itself against. Although up until current day space debris of this size has not caused any damage, a single collision with this type of space debris could be catastrophic to the ISS and the crew inhabiting it. This is becoming an increasing threat due to the increasing amount of space debris.

A number of solutions have already been proposed for the active removal of current (large) space debris (see the work of the previous groups covering this topic). However, a lot of these are still future ideas and not yet tested in practice. As long as space debris maintains and expands its undeniable presence in LEO, no spacecraft is safe from the dangers it presents. Therefore, action should be taken as soon as possible to ensure the safety of the ISS in relation to the particularly dangerous cm-sized space debris. For simplicity, we will mainly refer to this type of debris as ‘small debris’.

In recent years, research has been done on the development of space-based laser systems. These were mostly aimed at the active removal of space debris, without directly considering the immediate protection of the ISS. These laser systems are generally capable of ablating small debris in the low Earth Orbit and can have a range greatly exceeding contact-dependent removal systems. Therefore, such space-based removal systems may also have the potential to actively defend the ISS. In this report, we will investigate the feasibility of the incorporation of a defense system based on laser ablation on the ISS.

The system should be able to autonomously remediate threatening space debris before it can (critically) damage the ISS. This introduces new constraints to the existing space-based laser concepts. Most importantly, the limited time to react to space debris should be taken into consideration. An issue with the current detection and tracking systems, is the dependence on sufficient lighting (as these simply make use of a camera). Therefore, these systems can only operate during certain periods of the day. There could also be limited energy available, depending on the amount of energy used for other components of the ISS. It could also be problematic to place this new system on the ISS so that it works, but does not hinder other processes of the ISS (mass, blocking components).

Objectives

- Determine the requirements and the USE aspects related to the protection of the ISS from small debris using a laser system.

- Analyse the threat space debris poses to the ISS, based on characteristics of the debris as well as the ISS.

- Analyse the available detection, tracking and remediation systems in their ability to actively protect ISS from small space debris object.

- Combine the available systems into a single system to achieve the optimal solution.

- Implement and model the threat small debris poses to the ISS.

- Implement the chosen system in this model to test its feasibility.

Stakeholders

Space associations

- NASA (The United States)

- ROSKOSMOS (Russia)

- ESA (Europe)

- JAXA (Japan)

- CSA (Canada)

Ground control centers

These are the main control centers involved in the operation of the the ISS. They are all responsible for the proper functioning of their own modules and have continuous communication with other control centers and the ISS itself.

- NASA's Mission Control Center at Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas, serves as the primary control facility for the US segment of the ISS

- NASA's Payload Operations and Integration Center at Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, serves as the center that coordinates all payload operations in the US Segment. This center links Earth-bound researchers around the world with their experiments and astronauts aboard the International Space Station.

- Roskosmos's Mission Control Center at Korolyov, Moscow, controls the Russian Orbital Segment of the ISS, in addition to individual Soyuz and Progress missions.

- ESA's Columbus Control Center at the German Aerospace Center (DLR) in Oberpfaffenhofen, Germany, controls the European Columbus research laboratory.

- ESA's ATV Control Center, at the Toulouse Space Centre (CST) in Toulouse, France, controls flights of the unmanned European Automated Transfer Vehicle.

- JAXA's JEM Control Centre and HTV Control Centre at Tsukuba Space Center (TKSC) in Tsukuba, Japan, are responsible for operating the Japanese Experiment Module complex and all flights of the unmanned Japanese H-II Transfer Vehicle respectively.

- CSA's MSS Control at Saint-Hubert, Quebec, Canada, controls and monitors the Mobile Servicing System

Crew onboard of the ISS

Normally there are 6 people on board the ISS. Their main reponsibility is to perform experiment and repair malfunctioning parts of the ISS.

Requirements

- The method must be able to detect and track space debris of 1-10 cm within reasonable accuracy autonomously

- The method must be able to detect and track space debris within an x amount of seconds before potential impact in order to allow for action to be taken to protect the ISS (source)

- The method must be able to be operateable until at least 2030

- The method's costs must fit reasonably within the space associations budgets

- The method must be able to operate on the available energy produced by the ISS's solar panels, or the systems own solar panels

- The method must not add more dangerous space debris to the orbital environment

- The method's legislations must make sure the system can not be misused

USE aspects

User

There are two groups of users for this proposal. These are the astronauts and the ISS control centers. Currently, these two groups already work together in protecting the ISS. This specific collaboration is mostly focussed on the protecting the ISS (and the astronauts) from space debris bigger than ten centimeters. Debris of this size can be tracked (with radars) from the earth’s surface. When a piece of debris is observed and it comes to light that its orbit will bring it close to the ISS the astronauts receive a warning from the control center (in Houston). Depending on the chance of collision the astronauts either receive a yellow or red alert from the ground. The control center performs avoidance maneuvers based on these alerts and on the consequences of such maneuvers on mission objectives [1].

As said all these avoidance maneuvers are performed by mission control and the astronauts do not have to perform or activate any of these maneuvers themselves. They are however aware of when these maneuvers are happening. This would be different in the scenario for our proposal. It is very likely that in our proposal a piece of debris from one to ten centimeters could only be detected ten seconds before it would (potentially) hit the ISS. In this timeframe nor the control center nor the astronauts would be able to react in time. Therefore our system would be made autonomous. However, when our system activates and it performs defensive actions the control center and astronauts would initially have no insight in this. Therefore a feedback system is needed for them. A different system would need to be developed for both the control center(s) and the astronauts. The astronauts are focussed on performing their research and the control center is focussed on protecting the ISS among other things. Therefore, the space center would most likely want much more insight in the data gathered from an activation from our system. Whereas the might only want to be notified of its activation. As is the case now with the evasive maneuvers.

The feedback system for the control center would entail data on the detection of the debris, the effectiveness of the 'shot' and of the path of the debris after the 'shot'. Especially the latter is important since the debris might hit other satellites or pieces of debris on its (now accelerated) way down to earth. Avoiding these 'follow-up' collisions is possible however. The radars on earth have the ability to track debris above ten centimetres, as was mentioned above. If our system would have access to this data it could be able to calculate its 'shots' in a way that the piece of debris on collision course with the ISS would not hit any big pieces of debris on its now accelerated way down to earth.

Society

The main advantage of the ISS is the platform it provides for research. It's size and passengers give research institutions to perform research in zero gravity for a long-term period. The research conducted on the ISS is in fields of astrobiology, astronomy and materials science. The experiments in the ISS can be accessed and modified by the astronauts on the station on request of scientists on earth.

Concluding many research institutions on earth have a stake in the experiments conducted on the ISS. The advances are not only important for institutions in the field of astronomy, but in many more as well [2]. This means the whole of humanity gets benefit from the results of the experiments on the ISS.

The research on the ISS is located in different areas, mainly in especially allocated modules [3]. Were one of these modules to get damaged the (repair) costs would be great. The module would have to be replaced or repaired. Plus, the research inside the module could be lost or unusable. For this reason among other things research institutions (and the whole of humanity) benefits from (at least) the research modules being protected from space debris. Since, the research modules are used by institutions from different countries it would only be fair if each module is equally protected, because one cannot objectively say that for example American research is more important than say Indian research.

Enterprise

Five different space agencies are part of the ISS program, namely NASA (United States), Roscosmos (Russia), JAXA (Japan), ESA (Europe), and CSA (Canada). The ownership and use of the space station is established by intergovernmental treaties and agreements. The station is divided into two sections, a Russian and an American section [4].

All these space associations have put much money in building the station [5]. Seeing it get damaged by space debris is very undesirable for them. Therefore it would be in their interest to protect the station through for example our system. As said in the 'Society' section above it would be desirable if the whole of the ISS is equally protected and none of the space agencies is favoured by our system. Next to this it would be also desirable (if not required) if the system cannot be used maliciously. It should operate independently from interests from space agencies. The main goal should be to protect the ISS as a whole. To achieve this independent use one could say that each space agency invests the same amount of money and time in the system as the other agencies. Another option would be to have a commercial organization build the system, so that none of the space agencies should be able to claim ownership. In the end, the most important requirement would be to have the controlling group of the system be an independent organization, where employees from different space agencies work together.

Approach

The functioning of a laser system for remediation of space debris can be divided into three phases:

- Detection

- Tracking

- Remediation

In this report, the issues related to these phases as described in the problem statement will be researched and discussed. Furthermore, any other issues that emerge along the way will be identified and addressed. For each case, we will attempt to determine the most optimal solution in terms of feasibility and effectiveness of the laser system. In particular, we will focus on determining whether or not a laser remediation system could defend the ISS from small debris in a timely manner. To this end, we will first establish the characteristics of threatening space debris (such as impact velocity and density), as well as the characteristics of the ISS (such as its geometry and differences in vulnerability to space debris of its sections). In this way, we can determine the technical requirements such a remediation system must satisfy in order to actively defend the ISS from small debris. Furthermore, existing (concepts for) systems capable of executing one or more of the three phases described earlier will be identified and characterized in order to assess their ability to detect, track and ultimately fend off small space debris.

This information will then be combined in a model. By simulating incoming space debris and modeling a simplified representation of the ISS, the problem at hand can be assessed for a wide variety of conditions (in particular, debris with varying sizes and trajectories with respect to the ISS). Then, the proposed debris remediation methodology can be integrated and tested within the simulated environment. In case the proposed system cannot successfully defend the space station, suggestions will be made that could support the successful implementation of the system in the near future.

Milestones and Deliverables

Milestones

| Week | Milestone |

|---|---|

| 2 | Determined subject; defined plan |

| 3 | Find state of the art methods; finished literature search |

| 4 | Determine promising method(s) |

| 5 | Basic model |

| 6 | Final model |

| 7 | Results model, implement model in USE, finalized wiki |

| 8 | Presentation |

Deliverables:

- Wiki page

- Presentation

- Model/prototype

Planning

| Week | Task | Responsible member(s) |

|---|---|---|

| 2 |

|

|

| 3 |

|

|

| 4 |

|

|

| 5 |

What is the main purpose of the model? What kind of input and parameters are therefor relevant?

"analyze legislations and contracts on the ISS's model" "further develop the user's needs and possibly user's scenarios" "investigate how other active space-debris removal solution tackle the problem of misuse and possibly creating further threats"

|

|

| 6 |

|

|

| 7 |

|

|

| 8 |

|

|

Laser specifications

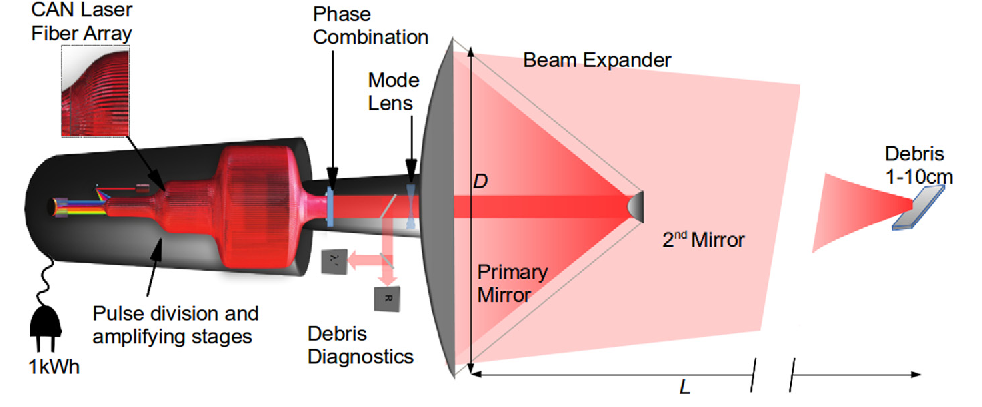

We will consider the specifications of the Coherent Amplification Network (CAN) laser, which is a novel fibre-based concept and was considered to be the laser system best fit for remediation of debris within the size range of 1-10 cm by Ebisuzaki et al. An intense beam can be produced by sending out a large sequence of laser pulses. For this specific purpose, a primary reason for choosing this laser is its high electrical efficiency. Of course, in order to fend off the debris heading towards the ISS with high relative velocities (of more than 10 km/s), a fast response and high average power is essential for successful defense. The most important specifics of the CAN laser system are as follows:

- The CAN laser system should be capable of the complete removal of debris fragments of sizes between 5 mm to 10 cm from orbit (without consideration of the time this would take).

- The laser system is capable of ablating debris at a distance of approximately 100 km from the ISS. Therefore, if we consider the relative velocity of space debris, the system generally has less than 10 seconds to fend off incoming debris.

- The proposed laser system consists of 104 fibers. Since each fiber can provide 1 mJ of laser energy, the total energy in a pulse is 10 J.

- In case the laser operates at high repetition rate (of 104 kHz), the laser can deliver average powers of about 100 kW.

- Through mechanical motion of primary and secondary mirrors, the beam can be steered and focused coarsely over a field of view of 10°.

- The response time of the CAN laser system is 3 seconds.

- Using phase control, the beam can be steered more precisely by about 0.05 mrad, with a precision of 0.01 μrad.

- Using trains of pulses, the laser system can evaluate the surface condition of the debris, allowing for optimal interaction between the beam and the debris.

However, it should be noted that many of these are conceptual in nature and haven’t been properly tested in practice yet. Since the system is still in development, further improvements could also be made in case this system proves to be insufficient for the defense of the ISS to small debris.

Energy available on the ISS

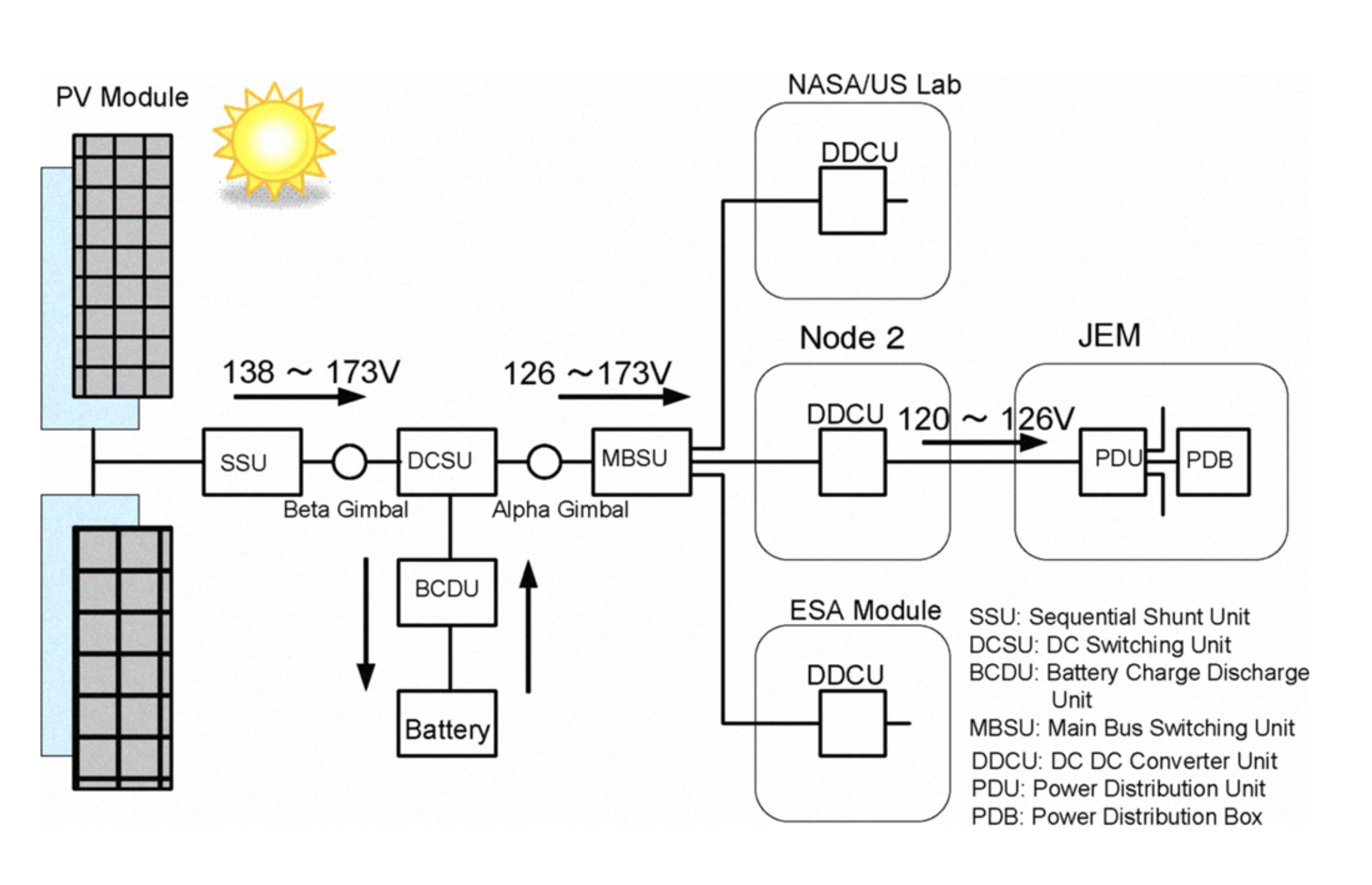

Solar wing array

Photovoltaic panels acquire most of the energy needed on the ISS. Only for the periodic propulsion the ISS uses fuel in the form of rocket propellant which is being refilled every now and then. The solar wings can generate up to 80 - 120 kW of electrical energy when sun is shining. At this point 60% of that energy is being used to charge ISS’s batteries. These batteries are used for the “eclipse” part of the ISS’s orbit, because then the solar wings produce almost no energy. The output voltage of the solar arrays is about 138V DC.

Conversion modules

First the voltage from the solar array is roughly regulated by the SSU, this makes sure the output voltage of the solar array does not have too much peaks or drops. Then the DCSU is used to switch between the input or output stages of the battery unit and the solar arrays. Then the MBSU does the switch regulating for the individual DDCU’s which convert the 173V DC to 120V DC which then will be used as power through the whole of the ISS.

Battery modules and the BCDU’s

As mentioned, the battery, is used to cover the ISS’s power usage when the solar array is not producing enough. The ISS has 24 Li-ion batteries together with 24 BCDU’s and they can have a maximum output of 158,4 kW.

Conclusion

Since the laser system would need to be operable at any time, even when the PV panels do not produce any electricity, it can only rely on the batteries maximum output of 158,4 kilowatts. Since the laser would not have to draw, when firing the laser, power for a longer period of time than approx. 1 minute . This means the capacity of the batteries would not be the bottleneck. Since the average power draw for the ISS is already 84 kilowatts, the laser can safely rely on using approx. 70 kilowatts at any point in time

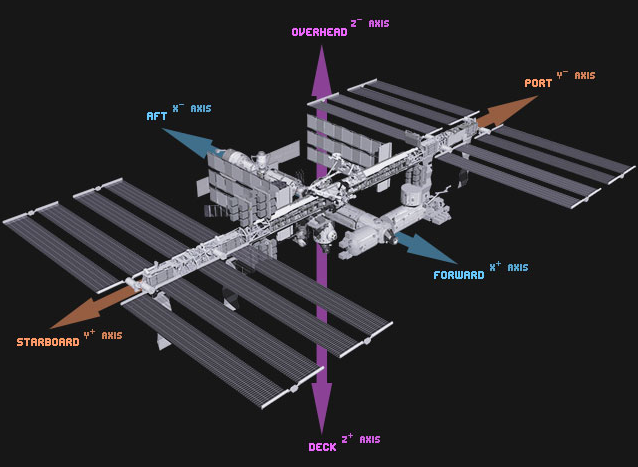

ISS and debris orientation

The total launch mass of the modules of the ISS is around 417.289 kg [2]. It consists of 14 pressurized modules, of which the habitable volume for the astronauts is 935 m3. Attached to this is the Main Truss, where the following components are attached, as is illustrated in Figure 2:

- Solar array wings can rotate, tracking the sun.

- Heat radiators rotate to stay in the shadow, radiating waste heat.

- Mobile servicing transporter travels on the rails along the Main Truss. It carries a 15-meter robotic arm.

The mean altitude on which the ISS orbits earth varies from about 330 km to 400 km, depending on the density of the atmosphere and operational circumstances. This means that the space station operates on a fairly low orbit within the low earth orbit (LEO). At this low altitude, drag makes space debris fall to the earth more, clearing the space of most space debris. However, due to the size of the ISS, it is still at risk of collisions.

The velocity needed for a stable orbit at the altitude of the ISS is about 7.7 km/s, so this is also roughly the velocity of the ISS. This means the space debris in this area will also roughly have this velocity, but this will vary more, since not all space debris is in a stable orbit. One full orbit around the earth takes about 90 minutes at this altitude. Since the orbit is not in the exact same direction as the rotation of the earth around its axis, the debris and ISS are all in a different place in their orbit and there is some unevenness in the gravitational field in the LEO, their paths can intersect in all possible direction in the orbit. The debris going in the same direction as the ISS will not have a high relative velocity to the ISS, so this will have no effect. In a head on collision, the impact velocity can go up to 16 km/s, which is roughly twice the stable orbit velocity.

When the velocity decreases, objects will fall to the earth. This means that debris in higher orbits that are slower than the stable orbit velocity will fall to the earth and possibly hit the ISS. The impact velocity of such a debris will also vary from 16 km/s to basically 0 km/s, depending on the angle. Since the debris comes from colliding satellites or other junk from space in a higher orbit, there will not be much debris going faster below the ISS and fly up against the ISS.

This means the dangerous debris impacts will occur at the front, sides (relative to its velocity) and the top (facing away from earth) of the ISS. The debris directing to the front has a relative velocity of around 10 km/s and the debris directing to the back a relative velocity of 2 km/s. Figure 3 indicates the forward direction of the ISS. The ISS has shields that can provide protection against high velocity impacts, these are especially used in the above mentioned areas. These shields can block an impact where the debris has a velocity of 4 km/s, but this damages the shield severely, leaving a crater in the shield. There are also some unprotected parts that can be hit, such as the solar panels.

It is crucial to determine where the laser system must be placed on the ISS exactly. Many aspects must be taken into account: for example, the laser must have a clear view of space, so that no parts of the ISS itself get in the way. Furthermore, the laser must be placed firmly on the space station and it must not weigh too much, which can cause imbalance of the whole. Lastly, the laser system should be placed where it can be reached by the astronauts, so that potential maintenance can be performed, such as reparations. These aspects must be considered in the design process of the laser system on the ISS.

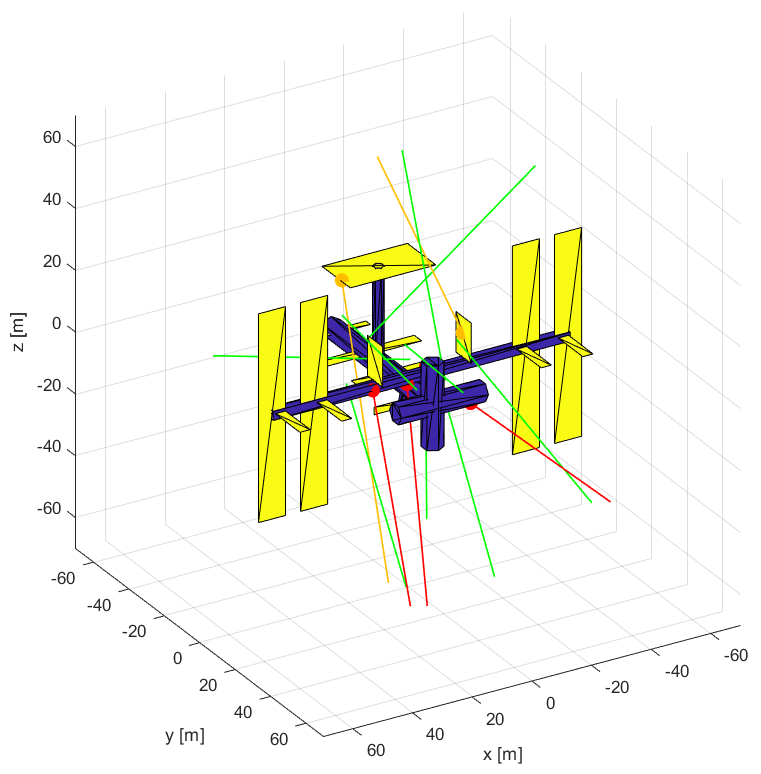

Model

A 3D model of the ISS, made by nasa [1] was heavily simplified and imported into Matlab using a python script. The model is represented as a mesh made of triangles. The debris is not visualized directly, only its path can be seen as a line. Using the Möller–Trumbore intersection algorithm [2] it can be determined if and where the debris hits the ISS. This is visualized in figure ?, where the following component can be seen:

- Yellow triangles form the body of the ISS.

- Dark blue triangles form the solar panels.

- Green lines represent the path of debris missing the ISS.

- Light blue lines represent the path of debris hitting a solar panel.

- Red lines represent the path of debris hitting the body of the ISS.

- Light blue and red circles mark the impact coordinates of the light blue and red lines respectively.

Code on GitHub: https://github.com/RobdeMooij/0LAUK0_USE_group_9

[1] https://nasa3d.arc.nasa.gov/detail/iss-6628 [2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/M%C3%B6ller%E2%80%93Trumbore_intersection_algorithm

References

[1] https://www.space.com/3-international-space-station.html

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Space_Station

[3] Ebisuzaki, T., Quinn, M. N., Wada, S., Wiktor, L., Takizawa, Y., Casolino, M., … Mourou, G. (2015). Acta Astronautica Demonstration designs for the remediation of space debris from the International Space Station. Acta Astronautica, 112, 102–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2015.03.004

[4] https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/multimedia/iss_labs_guide.html

[5] Phipps, C. R. (2014). LADROIT - A spaceborne ultraviolet laser system for space debris clearing. Acta Astronautica, 104(1), 243–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2014.08.007

Summary 25 scientific articles

- Dubanchet, V., Saussié, D., Alazard, D., Bérard, C., & Peuvédic, C. Le. (2015). Modeling and control of a space robot for active debris removal. CEAS Space Journal, 7(2), 203–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12567-015-0082-4

This paper focusses on the technical aspects of using a robotic arm on a ‘chaser’ satellite to capture large debris. This approach is considered to be the most realistic to actually be employed in the upcoming years. In the introduction, several efforts in achieving the modeling and control of such a system (in space) are outlined. In the second section, the main issues in achieving this are described. In the third and fourth section, an algorithm used to model and simulate the dynamics of this satellite and the method of controlling it are described. The resulting system is then simulated using Matlab (the code is provided in the paper).

- Flegel, S., Krisko, P., Gelhaus, J., Wiedemann, C., Möckel, M., Vörsmann, P., … Matney, M. (2010). Modeling the Space Debris Environment with MASTER2009 and ORDEM2010. Proceedings of the 38th COSPAR Scientific Assembly, (January).

This paper describes and compares two software tools (MASTER-2009 and ORDEM2010 developed by ESA and NASA respectively) used to describe debris orbiting the earth. The main goal of these tools is to estimate the object flux onto a specified target object and is therefore useful in achieving safe space travel. In MASTER, debris is simulated based on lists of known historical events responsible for scattering debris in earth’s orbit. Results are also validated using historical telescope/radar data. ORDEM is designed to reliably estimate orbital debris flux on spacecraft using telescope or radar fields-of-view. Therefore, both programs make heavy use of empirical data for their predictions. Results of the program deviate particularly in debris with a size of 1 mm to 1 cm. These bits of debris are particularly difficult to model, as the amount of measurement data is very small. Reasons for the deviation of the results for these small debris are described in the paper.

- Klinkrad, H. (2006). Space debris : models and risk analysis. Springer.

This book extensively covers space debris in general and describes the technical aspects of this debris in detail. In chapters 2 to 6, it is outlined how the space debris environment can be characterized and modelled using measurement data. Furthermore, it is explained how the future of space debris orbiting earth can be predicted and how this could be influenced by mitigation measures. Chapters 7 to 9 describe aspects of risk assessment and prevention within on-orbit shielding, collision avoidance and re-entry risk management. Chapter 10 gives an overview of the risks associated with natural meteoroids and meteorites. Lastly, chapter 11 overviews the importance of space debris research and international policy and standardization issues.

Understanding the causes and controlling its sources is essential to allow for safe space flight in the future. This can only be achieved through international cooperation. This has been done through international information exchange and international cooperation at a technical level. Furthermore, steps have already been taken in establishing space debris mitigation standards, guidelines, codes of conduct and policies by several space agencies, governmental bodies and international space operators.

- Yazdkhasti, S., & Sasiadek, J. Z. (2017). Space Robot Relative Navigation for Debris Removal. IFAC-PapersOnLine, 50(1), 7929–7934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ifacol.2017.08.767

In order for a ‘chaser’ (spacecraft capable of removing space debris) to properly navigate towards its target, it must be able to estimate the pose and motion of the target. In the introduction, several works addressing this problem are outlined. This paper presents a method to estimate the relative position, linear and angular velocity and the attitude of space debris using vision measurements (using stereo cameras). In order to estimate the relative states between spacecraft, the Multiplicative Extended Kalman Filter and Unscented Kalman Filter were applied. The methodology is described by first outlining the coordinate systems used. Afterwards, the estimation algorithm is described (in which a set of feature points tracked by a stereo camera are key). Then, the described algorithms are validated using a simulation experiment. This paper could be very interesting for our model. Perhaps we could translate the presented algorithm into a script and further build on it.

- Colmenarejo, P., Avilés, M., & di Sotto, E. (2015). Active debris removal GNC challenges over design and required ground validation. CEAS Space Journal, 7(2), 187–201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12567-015-0088-y

In this paper, proposed techniques for active debris removal (ADR) are categorized as follows:

- Contactless techniques (e.g. an ion beam), which can mostly build on existing techniques as opposed to using new ones

- Techniques requiring rigid contact (e.g. through a robotic arm), in which de-orbiting can be achieved by directly transmitting a force/torque to the debris

- Techniques requiring non-rigid contact (e.g. using flexible tentacles), which can entail intricate dynamics

A list of the proposed techniques can be retrieved from table 1 in the paper. As of yet, the most technologically advanced methods are the use of a robotic arm and capture through a tethered net.

Additionally, the main operational phases of active debris removal are outlined:

1. Ground controlled phase: In this phase, the “chaser” is brought closer to the target, usually not autonomously.

2. Fine orbit synchronization phase: The chaser moves to the (approximate) orbit of the target, which can be autonomous or partially using ground support

3. Short range phase: the final (passive) approach toward the target. Challenges here (which we could also address) are:

- Necessity to determine debris angular velocity and shape using optical observation, which most likely requires image processing techniques

- Necessity to synchronize the chaser with the angular motion of the debris

- In case of contact, necessity to de-tumble/control the resulting composite satellite

4. Terminal approach/capture

5. De-orbiting

Clearly, the fourth and fifth phase are very specific to the technique chosen for debris removal. Furthermore, the following aspects are discussed in the paper in detail:

1. Terminal approach using visual-based navigation

2. Ground validation of guidance, navigation and control systems based on hardware-in-the-loop test facilities

- Chen, S. (2011). The Space Debris Problem. Asian Perspective, 35(4), 537–558. https://doi.org/10.1353/apr.2011.0023

Near-Earth orbits are becoming congested as a result of an increase in the number of objects in space—operational satellites as well as orbital space debris. The risk of collisions between satellites and space debris is also growing. Suggested concepts for active removal of space debris: small-debris collection, ground-based lasers, trash tenders, dual-use orbit transfer vehicles, space-based lasers, and space tethers. There are two separate areas of concentration: small-debris elimination and individual large-object collection.

- Nishida, S.-I., Kawamoto, S., Okawa, Y., Terui, F., & Kitamura, S. (2009). Space debris removal system using a small satellite. Acta Astronautica, 65(1–2), 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2009.01.041

Electro-dynamic tether (EDT) technology, a possible high efficiency orbital transfer system, could provide a possible means for lowering the orbits of objects without the need for propellant.

- Ruggiero, A., Pergola, P., & Andrenucci, M. (2015). Small Electric Propulsion Platform for Active Space Debris Removal. IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science, 43(12), 4200–4209. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPS.2015.2491649

A deorbiting platform is in charge of approaching a target debris, bringing it to a lower altitude orbit and, in the case of a multiple target mission, releasing it and chasing a second one. Electric propulsion plays a key role in reducing the propellant mass consumption required for each maneuver and thus increasing the mass available to deorbit a relevant number of debris per mission.

- Huang, P., Zhang, F., Meng, Z., & Liu, Z. (2016). Adaptive control for space debris removal with uncertain kinematics, dynamics and states. Acta Astronautica, 128, 416–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2016.07.043

Tethered Space Robots are a promising solution for the space debris problem. Kinematics and dynamics parameters of the debris are unknown and parts of the states are unmeasurable according to the specifics of tether, which is a tough problem for the target retrieval/de-orbiting. Models and simulations can be used to get proposed parameters and their expected performances.

- Lampariello, R. (2013). On Grasping a Tumbling Debris Object with a Free-Flying Robot. IFAC Proceedings Volumes, 46(19), 161–166. https://doi.org/10.3182/20130902-5-DE-2040.00118

The grasping and stabilization of a tumbling, non-cooperative target satellite by means of a free-flying robot is a challenging control problem. A novel method for computing robot trajectories for grasping a tumbling target is presented. The problem is solved as a motion planning problem with nonlinear optimization. The resulting solution includes a first maneuver of the Servicer satellite which carries the robot arm, taking account of typical satellite control inputs. An analysis of the characteristics of the motion of a grasping point on a tumbling body is used to motivate this grasping method, which is argued to be useful for grasping targets of larger size.

- Klima, R., Bloemenbergen, D. (2016) Space debris removal: a game theoretical analysis https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4336/7/3/20

Space debris are a threat to operational spacecraft. Debris removal mission have been investigated by several space agencies to protect the satellites in the orbital environments. This costs a lot of money, but it has positive effect for all the satellites in the same orbital. A drawback is the agencies can all financially contribute to the debris removal or wait for others to do it. The risk of the latter is that the debris will be catastrophic. A game-theoretical analysis is presented where a realistic model of the orbit environment including all space objects are implemented. The experiments confirmed the predicted exponential growth of space debris near the Earth orbits. Active object removal are necessary.

- Liou, J.-C., Johnson, N. L. (2006). Risks in space from orbiting debris https://science.sciencemag.org/content/311/5759/340?casa_token=eKETqH8PDB4AAAAA:F0c9mUOMMHFELTaZbWngoc5wcDTKOkO0Ke0enr3v5kST6L-BQAsv6JItvTKWMiUkH2xrm2XAz7wm2Q

Since the launch of Sputnik I, an orbital debris environment has been created which has a risk on the space systems, including human space flight and robotic missions. More than 9000 orbiting objects with a total mass larger than 5 million kg are tracked by the U.S. Space Surveillance Network. Three collision have been occurred. There is a potential increase in Earth satellite population which results from the collisions of the space objects.

The current debris environment in the Low earth orbit (LEO) region is unstable and the collisions will become dominant in the future even without new launches. The collisions will happen between 900- and 1000 km over the next 200 years, which results in debris increase. Because undoubtedly new spacecraft will be launched in the future, the situation is even worse.

- Marco M. Castronuovo (2011)., Active space debris removal —A preliminary mission analysis and design, Pages 848-859, ISSN 0094-5765, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2011.04.017 .

(http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0094576511001287 )

The removal of 5 to 10 objects per year from the LEO can prevent the debris collisions from cascading. There are three orbital regions near the Earth where the collision occur and the sun-synchronous condition is the one we should target for debris removal. For this removal, a space mission has been designed with the goal to remove 5 rockets per year from this orbital environment. This space mission includes the launch of a satellite which contains de-orbiting devices. This satellite chooses an objects and grabs it with a robotic arm. A second arm puts a de-orbiting device to the object. Then the next target can be done. An active debris removal mission can de-orbit 35 large objects in 7 years and the mass budget is compatible.

- Shin-Ichiro Nishida, Satomi Kawamoto, (2011). Strategy for capturing of a tumbling space debris,Pages 113-120,ISSN 0094-5765,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2010.06.045 . (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0094576510002365 )

The capture of space debris objects are not favorable, because tracking errors lead to loading and momentum transfer occur during the capturing. Because the exact mass and inertial characteristics of the target are unknown due to unavailability or damage, it is harder to use the capture arm to capture the object. A “joint virtual depth control”algorithm for a force controlled robot arm control is used which tries to stop the rotation of the target with a brush type contactor. As a result, a new active space debris removal system is becoming more achievable.

- Vladimir Aslanov, Vadim Yudintsev, (2013). Dynamics of large space debris removal using tethered space tug, Pages 149-156, ISSN 0094-5765,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2013.05.020 . (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0094576513001811 )

Tethered systems are promising technology to reduce the space debris. This is possible in different ways: through momentum transfer or electrodynamic effects. Another way is using a tethered space tug which is attached to the space debris. Large space debris can cause a loss of control of the tethered space tug, so the problem of the removal of this large space debris is studied. The transportation system consists of a space debris and a space tug which are connected by the tether. The properties of this system on the motion of the system are studied, which includes the moments of inertia, the length and properties of tether, thruster force and initial condition of motion. The transportation process is possible when the space tug force is in the same direction as the tether and the tether is tensioned. There is minimal height of safe transportation below which the space tug can come into collision with the space debris.

- Nishida, S., & Yoshikawa, T. (2007). Capture and motion braking of space debris by a space robot. 2007 International Conference on Control, Automation and Systems. doi:10.1109/iccas.2007.4406990

(https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/4406990)

Space debris objects are generally tumbling in orbit, and so capturing and braking them involves complicated dynamical interactions between the object, the so-called "servicer" spacecraft, and its robot arm, with the possibility of strong loading occurring during the procedure. In this paper, a space debris capture strategy is described which proposes the application of joint virtual depth control to the capture robot arm. We present the results of simulations and experiments that confirm the feasibility of this technique.

- Nguyen-Huynh, T. C., & Sharf, I. (2013). Adaptive Reactionless Motion and Parameter Identification in Postcapture of Space Debris. Journal of Guidance, Control, and Dynamics, 36(2), 404-414. doi:10.2514/1.57856

(https://arc.aiaa.org/doi/10.2514/1.57856)

This paper presents a new control scheme for the problem of a space manipulator after capturing an unknown target, such as space debris. The changes in the dynamics parameters of the system, as a result of capturing an unknown target, must be accommodated because they may lead to poor performance of the trajectory control and attitude stabilization system. To address this issue in the postcapture scenario, the adaptive reactionless control algorithm to produce the arm motions with minimum disturbance to the base is proposed in this study. In addition, the online momentum-based estimation method is developed for inertia-parameter identification after the space manipulator grasps an unknown tumbling target with unknown angular momentum. This control scheme is intended for use in the transition phase from the instant of capture until the unknown parameters are identified and/or the available stabilization methods can be applied properly. To verify the validity and feasibility of the proposed concept, MSC.Adams simulation platform is employed to implement a planar base–manipulator–target model and the three-dimensional model of the Engineering Test Satellite VII system. The numerical results show that the space manipulator is able to perform reactionless motion while the inertial parameters converge to their real values.

- Kessler, D. J., & Cour-Palais, B. G. (1980). Collision Frequency of Artificial Satellites: Creation of a Debris Belt. Space Systems and Their Interactions with Earth's Space Environment, 707-736. doi:10.2514/5.9781600865459.0707.0736

(https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/JA083iA06p02637)

As the number of artificial satellites in earth orbit increases, the probability of collisions between satellites also increases. Satellite collisions would produce orbiting fragments, each of which would increase the probability of further collisions, leading to the growth of a belt of debris around the earth. This process parallels certain theories concerning the growth of the asteroid belt. The debris flux in such an earth‐orbiting belt could exceed the natural meteoroid flux, affecting future spacecraft designs. A mathematical model was used to predict the rate at which such a belt might form. Under certain conditions the belt could begin to form within this century and could be a significant problem during the next century. The possibility that numerous unobserved fragments already exist from spacecraft explosions would decrease this time interval. However, early implementation of specialized launch constraints and operational procedures could significantly delay the formation of the belt.

- Bennet, F., Conan, R., D’Orgeville, C., Murray, M., Paulin, N., Price, I., Rigaut, F., Ritchie, I., Smith, C., and Uhlendorf, K., “Adaptive optics for laser space debris removal”, in [SPIE Astronomical Telescopes+ Instrumentation], 844744–844744, International Society for Optics and Photonics (2012).

(https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258719228_Adaptive_Optics_For_Laser_Space_Debris_Removal)

Space debris in low Earth orbit below 1500km is becoming an increasing threat to satellites and spacecrafts. Radar and laser tracking are currently used to monitor the orbits of thousands of space debris and active satellites are able to use this information to manoeuvre out of the way of a predicted collision. However, many satellites are not able to manoeuvre and debris-on debris collisions are becoming a signicant contributor to the growing space debris population. The removal of the space debris from orbit is the preferred and more denitive solution. Space debris removal may be achieved through laser ablation, whereby a high power laser corrected with an adaptive optics system could, in theory, allow ablation of the debris surface and so impart a remote thrust on the targeted object. The goal of this is to avoid collisions between space debris to prevent an exponential increase in the number of space debris objects. We are developing an experiment to demonstrate the feasibility of laser ablation for space debris removal. This laser ablation demonstrator utilises a pulsed sodium laser to probe the atmosphere ahead of the space debris and the sun re ection of the space debris is used to provide atmospheric tip{tilt information. A deformable mirror is then shaped to correct an infrared laser beam on the uplink path to the debris. We present here the design and the expected performance of the system.

- Bradley, A. M., & Wein, L. M. (2009). Space debris: Assessing risk and responsibility. Advances in Space Research, 43(9), 1372-1390. doi:10.1016/j.asr.2009.02.006

(https://www.researchgate.net/publication/222563620_Space_debris_Assessing_risk_and_responsibility)

We model the orbital debris environment by a set of differential equations with parameter values that capture many of the complexities of existing three-dimensional simulation models. We compute the probability that a spacecraft gets destroyed in a collision during its operational lifetime, and then define the sustainable risk level as the maximum of this probability over all future time. Focusing on the 900- to 1000-km altitude region, which is the most congested portion of low Earth orbit, we find that – despite the initial rise in the level of fragments – the sustainable risk remains below 10-3 if there is high (>98%) compliance to the existing 25-year postmission deorbiting guideline. We quantify the damage (via the number of future destroyed operational spacecraft) generated by past and future space activities. We estimate that the 2007 FengYun 1C antisatellite weapon test represents ≈1% of the legacy damage due to space objects having a characteristic size of ⩾10 cm, and causes the same damage as failing to deorbit 2.6 spacecraft after their operational life. Although the political and economic issues are daunting, these damage estimates can be used to help determine one-time legacy fees and fees on future activities (including deorbit noncompliance), which can deter future debris generation, compensate operational spacecraft that are destroyed in future collisions, and partially fund research and development into space debris mitigation technologies. Our results need to be confirmed with a high-fidelity three-dimensional model before they can provide the basis for any major decisions made by the space community.