PRE2018 4 Group9

Group members

| Member | ID number |

|---|---|

| Rob de Mooij | 1017797 |

| Ilja van Oort | 1001232 |

| Sara Tjon | 1247050 |

| Thomas Pilaet | 0999458 |

| Joris Zandeberge | 1231962 |

Problem statement

The problem of space debris is becoming bigger and bigger. This debris consist of used rocket-stages, non-operational satellites, parts that where created through collisions and anti-satellite tests. Since the 70-ties this problem has been getting increasing attention and big space association like NASA and the ESA are constantly tracking this debris and preventing the creation of more. That is why most newly build satellites have built-in procedures that make sure the satellites de-orbit when they become out of order. However there has already been put a lot of material into orbit which still is creating risks for operational satellites and even more importantly the International Space Station (ISS). The ISS is constantly assessing the risks of space debris hitting it. From ground debris down to 10 centimeter in diameter can be tracked and therefore also avoided by the ISS. The ISS’s crucial parts are protected by a dual layer wall that shield them from debris smaller than a 1 cm diameter. The biggest danger for the ISS are therefore space-debris with a diameter apr. between 1 and 10 centimeter. While this till current day has not caused any damage, it is becoming a increasing problem due to the increasing amount of space debris. There are already a solutions being proposed for the removal of current space debris, however a lot of them are still future ideas and not yet tested in practice.

Objectives

- Determine the requirements and the USE aspects of the possible methods through which the ISS can be protected.

- Analyzing the available methods to actively protect ISS from objects with diameters between 1-10 cm.

- Develop a promising method / Combine several aspects into a new method.

- Implement and model the chosen method to test its feasibility.

Users and their requirements

Users:

- Satellite owners (governments, space associations)

Requirements:

- re-usable

- quick to implement

- hard to abuse

- versatile (for both smaller and larger debris)

- autonomous

- durable

- affordable

USE aspects

Laser specifications

Space debris orbit

The mean altitude on which the ISS orbits earth varies from about 330 km to 400 km, depending on the density of the atmosphere and operational circumstances. This means that the space station operates on a fairly low orbit within the low earth orbit (LEO). At this low altitude, drag makes space debris fall to the earth more, clearing the space of most space debris. However, due to the size of the ISS, it is still at risk of collisions.

The velocity needed for a stable orbit at the altitude of the ISS is about 7.7 km/s, so this is also roughly the velocity of the ISS. This means the space debris in this area will also roughly have this velocity, but this will vary more, since not all space debris is in a stable orbit. One full orbit around the earth takes about 90 minutes at this altitude. Since the orbit is not in the exact same direction as the rotation of the earth around its axis, the debris and ISS are all in a different place in their orbit and there is some unevenness in the gravitational field in the LEO, their paths can intersect in all possible direction in the orbit. The debris going in the same direction as the ISS will not have a high relative velocity to the ISS, so this will have no effect. In a head on collision, the impact velocity can go up to 16 km/s, which is roughly twice the stable orbit velocity.

When the velocity decreases, objects will fall to the earth. This means that debris in higher orbits that are slower than the stable orbit velocity will fall to the earth and possibly hit the ISS. The impact velocity of such a debris will also vary from 16 km/s to basically 0 km/s, depending on the angle. Since the debris comes from colliding satellites or other junk from space in a higher orbit, there will not be much debris going faster below the ISS and fly up against the ISS.

This means the dangerous debris impacts will occur at the front, sides (relative to its velocity) and the top (facing away from earth) of the ISS. The ISS has shields that can provide protection against high velocity impacts, these are especially used in the above mentioned areas. These shields can block an impact where the debris has a velocity of 4 km/s, but this damages the shield severely, leaving a crater in the shield. The average impact velocity of the debris is 10.5 km/s and there are also some unprotected parts that can be hit, such as the solar panels.

ISS orientation and laser placement

It is crucial to determine where the laser system must be placed on the ISS exactly. Many aspects must be taken into account: for example, the laser must have a clear view of space, so that no parts of the ISS itself get in the way. Furthermore, the laser must be placed firmly on the space station and it must not weigh too much, which can cause imbalance of the whole. Lastly, the laser system should be placed where it can be reached by the astronauts, so that potential maintenance can be performed, such as reparations. These aspects must be considered in the design process of the laser system on the ISS.

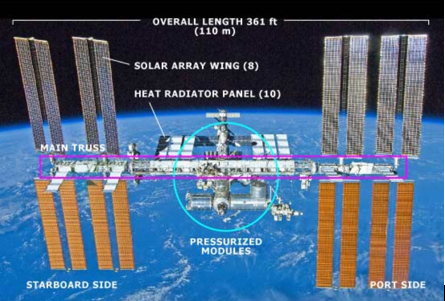

Firstly, the structure of the ISS is investigated. Most of the ISS structure consists of aluminium and its total launch mass of the modules is around 417.289 kg [2]. It consists of 14 pressurized modules, of which the habitable volume for the astronauts is 935 m3. Attached to this is the Main Truss, where the following components are attached, as is illustrated in Figure 1: [1]

- Solar array wings can rotate, tracking the sun.

- Heat radiators rotate to stay in the shadow, radiating waste heat.

- Mobile servicing transporter travels on the rails along the Main Truss. It carries a 15-meter robotic arm.

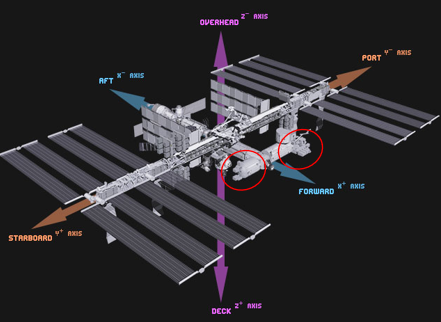

There are two types of operational modes: backward and forward modes. In the backward direction 180 ± 15 degrees, the relative velocity of the debris relative to the ISS is less than 2 km/s and the flux is around 10-7 m-2 yr-1. Thus in this direction, rapid tracking and removal of the debris is not that necessary. In a forward direction, for example (50 ± 15) degrees relative to the direction in which the ISS moves, the relative velocity of the debris is higher (around 10 km/s), and the flux is larger, namely 2•10-6 m-2 yr-1, which makes the removal of small debris possible [3]. So, it is more efficient to focus on the debris which comes from the forward direction, because in this direction the debris can be detected and removed more easily than in the backward direction. Figure 2 indicates the forward direction of the ISS.

Considering the fact that a laser has a field of view of 30 degrees, one laser is not enough to protect the full pressurized human habitable modules of the ISS. If two laser systems are placed on the two red circled areas area, a part of the pressurized human habitable modules, the field of view is larger and there is more balance due to the symmetry than when only a single laser is placed. The placement of these lasers is then on the front of the ISS. Furthermore, they are close to the entrance and exit of the ISS, so the astronauts can easily reach the laser system to perform operations on it, in case repairs are necessary. Lastly, the lasers have a clear view of the space when used here. The mass of one laser is around 2500 kg [5] so two lasers would be 5000 kg, which is negligible compared to the total mass of the ISS, so it is expected that the placement of the laser will not influence the centre of mass and the balance of the ISS.

References

[1] https://www.space.com/3-international-space-station.html

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Space_Station

[3] Ebisuzaki, T., Quinn, M. N., Wada, S., Wiktor, L., Takizawa, Y., Casolino, M., … Mourou, G. (2015). Acta Astronautica Demonstration designs for the remediation of space debris from the International Space Station. Acta Astronautica, 112, 102–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2015.03.004

[4] https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/multimedia/iss_labs_guide.html

[5] Phipps, C. R. (2014). LADROIT - A spaceborne ultraviolet laser system for space debris clearing. Acta Astronautica, 104(1), 243–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2014.08.007

Approach, milestone and deliverables

Approach:

Reading papers to get a good picture of the current problem and the state-of-the-art technology

Analyzing and comparing possible methods for space debris removal by looking at their pros and cons

Further development of a (combination of) promising technique(s) with a model or prototype.

Milestones:

Week 2: Determined subject; defined plan

Week 3: Find state of the art methods; finished literature search

Week 4: Determine promising method(s)

Week 5: Basic model

Week 6: Final model

Week 7: Results model, implement model in USE, finalized wiki

Week 8: Presentation

Deliverables

- Wiki page

- Presentation

- Model/prototype

Planning

| Week | Task | Responsible member(s) |

|---|---|---|

| 2 |

|

|

| 3 |

|

|

| 4 |

|

|

| 5 |

|

|

| 6 |

|

|

| 7 |

|

|

| 8 |

|

|

Defense techniques

Laser

The first defense technique used to remove space debris is to use laser pulses. The operation is executed in three stages:

1. Passive detecting of cm-size debris with a super-wide field of view (FOV) camera: this is possible via reflected sunlight in the twilight part of the orbit. The Earth is in night and the satellite and debris are sunlit. For the ISS, this is about 5 minutes at every orbit of 90 minutes. The amount of photons that is reflected by the debris can be determined using the EUSO telescope. A linear track trigger algorithm can be used for detection of small high velocity debris objects by tracking its movement. From this the minimum detectable debris size can be calculated, as the maximum detection distance. Now the debris tracking system is evoked.

2. Active tracking by a narrow FOV telescope: with the EUSO there is an accuracy of 0.08 degrees of the pixel size and we must track the debris within this accuracy. Used are a combined pulsed laser and a telescope consistent with the determination of accuracy of the detection. Laser pulses are sent to the debris object. By analysing the number of photons reflected by the debris, a three dimensional position of the debris is determined.

3. Velocity modification by laser ablation: space debris that is smaller than 10 cm can be decelerated by the laser impulses, which results in re-entry in the Earth’s atmosphere. The effects of debris spin or orientation with respect to the laser pulse direction are not considered, but with high repetition laser pulses, the angular velocity and orientation can fastly be determined.

There are some design factors of the laser system which should be considered when operating on-board the ISS. Important is the high electrical efficiency of the laser system. Also, a fast response and good power are necessary. According to the authors, the CAN laser system best realizes these factors.

Ultimately, the range of detection/removal can be up to 100 km from the ISS orbit. Laser impulse control can also be used to modify the rotation rate of large debris objects like satellites or rockets.

Orbital debris spotter

An orbital debris spotter is a possible solution for the more detailed detection of small space debris. The concept for the orbital debris detection sensor is to create a light sheet with a light source like a low power laser and a conic mirror. When an orbital debris objects goes through the laser sheet, the object will reflect, scatter, transmit and/or absorb the light. Part of the scattered light is detected by a CCD camera with a wide angle lens. In this way debris that passes the spacecraft is detected near real-time, with the range of a few meters.

The orbital debris spotter would also be used to prevent collisions of space debris objects with the ISS. By using satellites near the ISS equipped with this technology, these could signal the ISS once they detect a threatening object, allowing the space station to safely avoid (or, destroy) the object.

Fishing

For a new mission, called RemoveDebris, a 1-cubic-meter spacecraft is launched to the space station. Soon, a spacecraft may be able to use a net, a harpoon or a drag sail to capture space debris objects. It is mentioned that the use of an electrodynamic tether failed in 2017 because the tether could not unroll and deploy.

- Net capture: a CubeSat will be released that will deploy and inflate a balloon of 1 meter to make itself into a target. After drifting 6 meters away, a 5-meter-wide net will be launched at the target. The masses on the edges of the net will wrap carefully around the target. Spools will tighten the neck of the net to prevent the CubeSat from escaping. The target will be placed in the orbit so it can burn up in the atmosphere of the Earth.

- Harpoon Capture: the spacecraft will use a long arm to hold a stationary target. When the target is placed at a distance of 1.5 meters, a small harpoon is fired that consists of a miniature projectile with a trailing tether. The tether allows the spacecraft to reel in its target.

- Drag Sail: the test with the drag sail is to prevent the spacecraft from becoming space debris itself. On the end of a mast, a drag sail is raised that extends to 1 meter, so the sail does not entangle the spacecraft. A motor raises carbon fiber booms that open the sails membrane, which is around 10 square meters. This drag sail makes the spacecraft leave the orbit fast and makes an end to the mission.

Tether-net capture

The use of tether-nets to capture space debris is a promising strategie for the Active Debris Removal mission, especially for large debris. The concept is as follows: a net is shot out deploy and envelope space debris, and then it is pulled by the “chaser” with a tether to control the de-orbiting and eventually releases the debris into the atmosphere of the Earth. The tethered square net contains several masses to the net perimeter at the corner, which wraps around the debris to be captured. An alternative method without the use of the corner masses, is to use tether-net modules where pressurized gas is used to capture the debris. A single launch could result in the de-orbiting of several objects. The tether-net solution is considered useful to capture space debris of different shapes, sizes and motions.

Summary 25 scientific articles

- Dubanchet, V., Saussié, D., Alazard, D., Bérard, C., & Peuvédic, C. Le. (2015). Modeling and control of a space robot for active debris removal. CEAS Space Journal, 7(2), 203–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12567-015-0082-4

This paper focusses on the technical aspects of using a robotic arm on a ‘chaser’ satellite to capture large debris. This approach is considered to be the most realistic to actually be employed in the upcoming years. In the introduction, several efforts in achieving the modeling and control of such a system (in space) are outlined. In the second section, the main issues in achieving this are described. In the third and fourth section, an algorithm used to model and simulate the dynamics of this satellite and the method of controlling it are described. The resulting system is then simulated using Matlab (the code is provided in the paper).

- Flegel, S., Krisko, P., Gelhaus, J., Wiedemann, C., Möckel, M., Vörsmann, P., … Matney, M. (2010). Modeling the Space Debris Environment with MASTER2009 and ORDEM2010. Proceedings of the 38th COSPAR Scientific Assembly, (January).

This paper describes and compares two software tools (MASTER-2009 and ORDEM2010 developed by ESA and NASA respectively) used to describe debris orbiting the earth. The main goal of these tools is to estimate the object flux onto a specified target object and is therefore useful in achieving safe space travel. In MASTER, debris is simulated based on lists of known historical events responsible for scattering debris in earth’s orbit. Results are also validated using historical telescope/radar data. ORDEM is designed to reliably estimate orbital debris flux on spacecraft using telescope or radar fields-of-view. Therefore, both programs make heavy use of empirical data for their predictions. Results of the program deviate particularly in debris with a size of 1 mm to 1 cm. These bits of debris are particularly difficult to model, as the amount of measurement data is very small. Reasons for the deviation of the results for these small debris are described in the paper.

- Klinkrad, H. (2006). Space debris : models and risk analysis. Springer.

This book extensively covers space debris in general and describes the technical aspects of this debris in detail. In chapters 2 to 6, it is outlined how the space debris environment can be characterized and modelled using measurement data. Furthermore, it is explained how the future of space debris orbiting earth can be predicted and how this could be influenced by mitigation measures. Chapters 7 to 9 describe aspects of risk assessment and prevention within on-orbit shielding, collision avoidance and re-entry risk management. Chapter 10 gives an overview of the risks associated with natural meteoroids and meteorites. Lastly, chapter 11 overviews the importance of space debris research and international policy and standardization issues.

Understanding the causes and controlling its sources is essential to allow for safe space flight in the future. This can only be achieved through international cooperation. This has been done through international information exchange and international cooperation at a technical level. Furthermore, steps have already been taken in establishing space debris mitigation standards, guidelines, codes of conduct and policies by several space agencies, governmental bodies and international space operators.

- Yazdkhasti, S., & Sasiadek, J. Z. (2017). Space Robot Relative Navigation for Debris Removal. IFAC-PapersOnLine, 50(1), 7929–7934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ifacol.2017.08.767

In order for a ‘chaser’ (spacecraft capable of removing space debris) to properly navigate towards its target, it must be able to estimate the pose and motion of the target. In the introduction, several works addressing this problem are outlined. This paper presents a method to estimate the relative position, linear and angular velocity and the attitude of space debris using vision measurements (using stereo cameras). In order to estimate the relative states between spacecraft, the Multiplicative Extended Kalman Filter and Unscented Kalman Filter were applied. The methodology is described by first outlining the coordinate systems used. Afterwards, the estimation algorithm is described (in which a set of feature points tracked by a stereo camera are key). Then, the described algorithms are validated using a simulation experiment. This paper could be very interesting for our model. Perhaps we could translate the presented algorithm into a script and further build on it.

- Colmenarejo, P., Avilés, M., & di Sotto, E. (2015). Active debris removal GNC challenges over design and required ground validation. CEAS Space Journal, 7(2), 187–201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12567-015-0088-y

In this paper, proposed techniques for active debris removal (ADR) are categorized as follows:

- Contactless techniques (e.g. an ion beam), which can mostly build on existing techniques as opposed to using new ones

- Techniques requiring rigid contact (e.g. through a robotic arm), in which de-orbiting can be achieved by directly transmitting a force/torque to the debris

- Techniques requiring non-rigid contact (e.g. using flexible tentacles), which can entail intricate dynamics

A list of the proposed techniques can be retrieved from table 1 in the paper. As of yet, the most technologically advanced methods are the use of a robotic arm and capture through a tethered net.

Additionally, the main operational phases of active debris removal are outlined:

1. Ground controlled phase: In this phase, the “chaser” is brought closer to the target, usually not autonomously.

2. Fine orbit synchronization phase: The chaser moves to the (approximate) orbit of the target, which can be autonomous or partially using ground support

3. Short range phase: the final (passive) approach toward the target. Challenges here (which we could also address) are:

- Necessity to determine debris angular velocity and shape using optical observation, which most likely requires image processing techniques

- Necessity to synchronize the chaser with the angular motion of the debris

- In case of contact, necessity to de-tumble/control the resulting composite satellite

4. Terminal approach/capture

5. De-orbiting

Clearly, the fourth and fifth phase are very specific to the technique chosen for debris removal. Furthermore, the following aspects are discussed in the paper in detail:

1. Terminal approach using visual-based navigation

2. Ground validation of guidance, navigation and control systems based on hardware-in-the-loop test facilities

- Chen, S. (2011). The Space Debris Problem. Asian Perspective, 35(4), 537–558. https://doi.org/10.1353/apr.2011.0023

Near-Earth orbits are becoming congested as a result of an increase in the number of objects in space—operational satellites as well as orbital space debris. The risk of collisions between satellites and space debris is also growing. Suggested concepts for active removal of space debris: small-debris collection, ground-based lasers, trash tenders, dual-use orbit transfer vehicles, space-based lasers, and space tethers. There are two separate areas of concentration: small-debris elimination and individual large-object collection.

- Nishida, S.-I., Kawamoto, S., Okawa, Y., Terui, F., & Kitamura, S. (2009). Space debris removal system using a small satellite. Acta Astronautica, 65(1–2), 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2009.01.041

Electro-dynamic tether (EDT) technology, a possible high efficiency orbital transfer system, could provide a possible means for lowering the orbits of objects without the need for propellant.

- Ruggiero, A., Pergola, P., & Andrenucci, M. (2015). Small Electric Propulsion Platform for Active Space Debris Removal. IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science, 43(12), 4200–4209. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPS.2015.2491649

A deorbiting platform is in charge of approaching a target debris, bringing it to a lower altitude orbit and, in the case of a multiple target mission, releasing it and chasing a second one. Electric propulsion plays a key role in reducing the propellant mass consumption required for each maneuver and thus increasing the mass available to deorbit a relevant number of debris per mission.

- Huang, P., Zhang, F., Meng, Z., & Liu, Z. (2016). Adaptive control for space debris removal with uncertain kinematics, dynamics and states. Acta Astronautica, 128, 416–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2016.07.043

Tethered Space Robots are a promising solution for the space debris problem. Kinematics and dynamics parameters of the debris are unknown and parts of the states are unmeasurable according to the specifics of tether, which is a tough problem for the target retrieval/de-orbiting. Models and simulations can be used to get proposed parameters and their expected performances.

- Lampariello, R. (2013). On Grasping a Tumbling Debris Object with a Free-Flying Robot. IFAC Proceedings Volumes, 46(19), 161–166. https://doi.org/10.3182/20130902-5-DE-2040.00118

The grasping and stabilization of a tumbling, non-cooperative target satellite by means of a free-flying robot is a challenging control problem. A novel method for computing robot trajectories for grasping a tumbling target is presented. The problem is solved as a motion planning problem with nonlinear optimization. The resulting solution includes a first maneuver of the Servicer satellite which carries the robot arm, taking account of typical satellite control inputs. An analysis of the characteristics of the motion of a grasping point on a tumbling body is used to motivate this grasping method, which is argued to be useful for grasping targets of larger size.

- Klima, R., Bloemenbergen, D. (2016) Space debris removal: a game theoretical analysis https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4336/7/3/20

Space debris are a threat to operational spacecraft. Debris removal mission have been investigated by several space agencies to protect the satellites in the orbital environments. This costs a lot of money, but it has positive effect for all the satellites in the same orbital. A drawback is the agencies can all financially contribute to the debris removal or wait for others to do it. The risk of the latter is that the debris will be catastrophic. A game-theoretical analysis is presented where a realistic model of the orbit environment including all space objects are implemented. The experiments confirmed the predicted exponential growth of space debris near the Earth orbits. Active object removal are necessary.

- Liou, J.-C., Johnson, N. L. (2006). Risks in space from orbiting debris https://science.sciencemag.org/content/311/5759/340?casa_token=eKETqH8PDB4AAAAA:F0c9mUOMMHFELTaZbWngoc5wcDTKOkO0Ke0enr3v5kST6L-BQAsv6JItvTKWMiUkH2xrm2XAz7wm2Q

Since the launch of Sputnik I, an orbital debris environment has been created which has a risk on the space systems, including human space flight and robotic missions. More than 9000 orbiting objects with a total mass larger than 5 million kg are tracked by the U.S. Space Surveillance Network. Three collision have been occurred. There is a potential increase in Earth satellite population which results from the collisions of the space objects.

The current debris environment in the Low earth orbit (LEO) region is unstable and the collisions will become dominant in the future even without new launches. The collisions will happen between 900- and 1000 km over the next 200 years, which results in debris increase. Because undoubtedly new spacecraft will be launched in the future, the situation is even worse.

- Marco M. Castronuovo (2011)., Active space debris removal —A preliminary mission analysis and design, Pages 848-859, ISSN 0094-5765, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2011.04.017 .

(http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0094576511001287 )

The removal of 5 to 10 objects per year from the LEO can prevent the debris collisions from cascading. There are three orbital regions near the Earth where the collision occur and the sun-synchronous condition is the one we should target for debris removal. For this removal, a space mission has been designed with the goal to remove 5 rockets per year from this orbital environment. This space mission includes the launch of a satellite which contains de-orbiting devices. This satellite chooses an objects and grabs it with a robotic arm. A second arm puts a de-orbiting device to the object. Then the next target can be done. An active debris removal mission can de-orbit 35 large objects in 7 years and the mass budget is compatible.

- Shin-Ichiro Nishida, Satomi Kawamoto, (2011). Strategy for capturing of a tumbling space debris,Pages 113-120,ISSN 0094-5765,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2010.06.045 . (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0094576510002365 )

The capture of space debris objects are not favorable, because tracking errors lead to loading and momentum transfer occur during the capturing. Because the exact mass and inertial characteristics of the target are unknown due to unavailability or damage, it is harder to use the capture arm to capture the object. A “joint virtual depth control”algorithm for a force controlled robot arm control is used which tries to stop the rotation of the target with a brush type contactor. As a result, a new active space debris removal system is becoming more achievable.

- Vladimir Aslanov, Vadim Yudintsev, (2013). Dynamics of large space debris removal using tethered space tug, Pages 149-156, ISSN 0094-5765,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2013.05.020 . (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0094576513001811 )

Tethered systems are promising technology to reduce the space debris. This is possible in different ways: through momentum transfer or electrodynamic effects. Another way is using a tethered space tug which is attached to the space debris. Large space debris can cause a loss of control of the tethered space tug, so the problem of the removal of this large space debris is studied. The transportation system consists of a space debris and a space tug which are connected by the tether. The properties of this system on the motion of the system are studied, which includes the moments of inertia, the length and properties of tether, thruster force and initial condition of motion. The transportation process is possible when the space tug force is in the same direction as the tether and the tether is tensioned. There is minimal height of safe transportation below which the space tug can come into collision with the space debris.

- Nishida, S., & Yoshikawa, T. (2007). Capture and motion braking of space debris by a space robot. 2007 International Conference on Control, Automation and Systems. doi:10.1109/iccas.2007.4406990

(https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/4406990)

Space debris objects are generally tumbling in orbit, and so capturing and braking them involves complicated dynamical interactions between the object, the so-called "servicer" spacecraft, and its robot arm, with the possibility of strong loading occurring during the procedure. In this paper, a space debris capture strategy is described which proposes the application of joint virtual depth control to the capture robot arm. We present the results of simulations and experiments that confirm the feasibility of this technique.

- Nguyen-Huynh, T. C., & Sharf, I. (2013). Adaptive Reactionless Motion and Parameter Identification in Postcapture of Space Debris. Journal of Guidance, Control, and Dynamics, 36(2), 404-414. doi:10.2514/1.57856

(https://arc.aiaa.org/doi/10.2514/1.57856)

This paper presents a new control scheme for the problem of a space manipulator after capturing an unknown target, such as space debris. The changes in the dynamics parameters of the system, as a result of capturing an unknown target, must be accommodated because they may lead to poor performance of the trajectory control and attitude stabilization system. To address this issue in the postcapture scenario, the adaptive reactionless control algorithm to produce the arm motions with minimum disturbance to the base is proposed in this study. In addition, the online momentum-based estimation method is developed for inertia-parameter identification after the space manipulator grasps an unknown tumbling target with unknown angular momentum. This control scheme is intended for use in the transition phase from the instant of capture until the unknown parameters are identified and/or the available stabilization methods can be applied properly. To verify the validity and feasibility of the proposed concept, MSC.Adams simulation platform is employed to implement a planar base–manipulator–target model and the three-dimensional model of the Engineering Test Satellite VII system. The numerical results show that the space manipulator is able to perform reactionless motion while the inertial parameters converge to their real values.

- Kessler, D. J., & Cour-Palais, B. G. (1980). Collision Frequency of Artificial Satellites: Creation of a Debris Belt. Space Systems and Their Interactions with Earth's Space Environment, 707-736. doi:10.2514/5.9781600865459.0707.0736

(https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/JA083iA06p02637)

As the number of artificial satellites in earth orbit increases, the probability of collisions between satellites also increases. Satellite collisions would produce orbiting fragments, each of which would increase the probability of further collisions, leading to the growth of a belt of debris around the earth. This process parallels certain theories concerning the growth of the asteroid belt. The debris flux in such an earth‐orbiting belt could exceed the natural meteoroid flux, affecting future spacecraft designs. A mathematical model was used to predict the rate at which such a belt might form. Under certain conditions the belt could begin to form within this century and could be a significant problem during the next century. The possibility that numerous unobserved fragments already exist from spacecraft explosions would decrease this time interval. However, early implementation of specialized launch constraints and operational procedures could significantly delay the formation of the belt.

- Bennet, F., Conan, R., D’Orgeville, C., Murray, M., Paulin, N., Price, I., Rigaut, F., Ritchie, I., Smith, C., and Uhlendorf, K., “Adaptive optics for laser space debris removal”, in [SPIE Astronomical Telescopes+ Instrumentation], 844744–844744, International Society for Optics and Photonics (2012).

(https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258719228_Adaptive_Optics_For_Laser_Space_Debris_Removal)

Space debris in low Earth orbit below 1500km is becoming an increasing threat to satellites and spacecrafts. Radar and laser tracking are currently used to monitor the orbits of thousands of space debris and active satellites are able to use this information to manoeuvre out of the way of a predicted collision. However, many satellites are not able to manoeuvre and debris-on debris collisions are becoming a signicant contributor to the growing space debris population. The removal of the space debris from orbit is the preferred and more denitive solution. Space debris removal may be achieved through laser ablation, whereby a high power laser corrected with an adaptive optics system could, in theory, allow ablation of the debris surface and so impart a remote thrust on the targeted object. The goal of this is to avoid collisions between space debris to prevent an exponential increase in the number of space debris objects. We are developing an experiment to demonstrate the feasibility of laser ablation for space debris removal. This laser ablation demonstrator utilises a pulsed sodium laser to probe the atmosphere ahead of the space debris and the sun re ection of the space debris is used to provide atmospheric tip{tilt information. A deformable mirror is then shaped to correct an infrared laser beam on the uplink path to the debris. We present here the design and the expected performance of the system.

- Bradley, A. M., & Wein, L. M. (2009). Space debris: Assessing risk and responsibility. Advances in Space Research, 43(9), 1372-1390. doi:10.1016/j.asr.2009.02.006

(https://www.researchgate.net/publication/222563620_Space_debris_Assessing_risk_and_responsibility)

We model the orbital debris environment by a set of differential equations with parameter values that capture many of the complexities of existing three-dimensional simulation models. We compute the probability that a spacecraft gets destroyed in a collision during its operational lifetime, and then define the sustainable risk level as the maximum of this probability over all future time. Focusing on the 900- to 1000-km altitude region, which is the most congested portion of low Earth orbit, we find that – despite the initial rise in the level of fragments – the sustainable risk remains below 10-3 if there is high (>98%) compliance to the existing 25-year postmission deorbiting guideline. We quantify the damage (via the number of future destroyed operational spacecraft) generated by past and future space activities. We estimate that the 2007 FengYun 1C antisatellite weapon test represents ≈1% of the legacy damage due to space objects having a characteristic size of ⩾10 cm, and causes the same damage as failing to deorbit 2.6 spacecraft after their operational life. Although the political and economic issues are daunting, these damage estimates can be used to help determine one-time legacy fees and fees on future activities (including deorbit noncompliance), which can deter future debris generation, compensate operational spacecraft that are destroyed in future collisions, and partially fund research and development into space debris mitigation technologies. Our results need to be confirmed with a high-fidelity three-dimensional model before they can provide the basis for any major decisions made by the space community.