PRE2017 4 Groep5

Group Members

| Name | Study | Student ID |

|---|---|---|

| Ahmed Ahres | Software Science | 0978238 |

| Quinten Maes | Psychology & Technology | 0955972 |

| Hugo Melchers | Mathematics & Software Science | 0994280 |

| Christel van den Nieuwenhuizen | Psychology & Technology | 0940672 |

| Frank de Veld | Physics & Mathematics | 1010914 |

Introduction

Automation is one of the biggest changes taking place in industry today. Nowadays, systems are being automated to the extent that they require almost no human intervention. Such a technology has been successful not only in manufacturing, but also in the automotive industries. Self-driving cars or even drones are examples of where automation has seen research and development in flight.

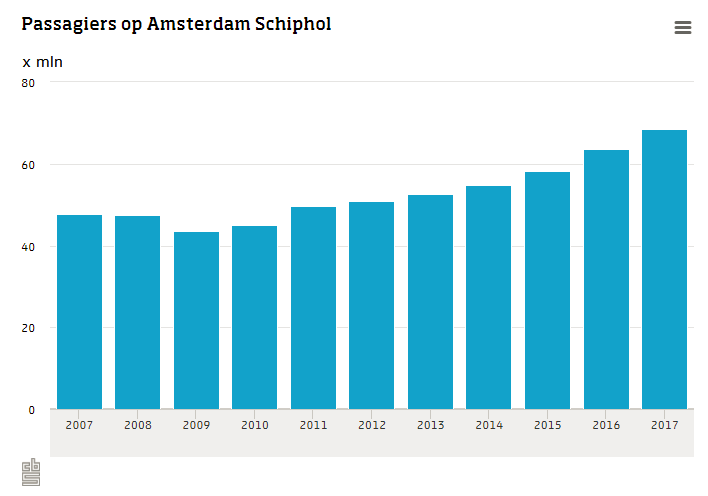

Suitcases are also an example that can benefit from automation. By making suitcases autonomously follow their owner, we can facilitate the traveling process by making it less tiring, especially for the elderly, disabled people and pregnant women. Moreover, this would allow a more efficient transportation of clothes and objects, which could be useful for business travelers or regular flyers.The user group grows every year if we look at the increasing amount of flying travelers, see fig 1. [1] Research has shown that people were enthusiastic and trustworthy towards a prototype of a robotic suitcase after using it [2]. However, one must keep in mind aspects such as security, object detection and components to be able to fit in a plane according to airport security standards.

We first planned to develop a smart self-following suitcase in order to make traveling and transporting objects more efficient and less tiring. This system required different technologies: Bluetooth connection to be able to follow a device owned by a person, GPS tracking to avoid getting lost by the owner, security procedures to avoid getting stolen and computer vision for obstacle avoidance. The plan was to make framework to build such a system, present an object detection algorithm that can be used by the suitcase for obstacle avoidance as well as a user interface for a mobile application that can be used by the owner of our system. However, after deliberation it became clear that this was a very complex project and that an easier solution exists for the same problem, namely an engine assisting suitcase which relieves the load of the suitcase by detecting the direction of movement from the pull of the user and using a small motor to ride in that direction itself too. There is thus a shared-control system present. With a separate smartphone application it is possible to tune the amount of work done by the suitcase. The advantages of this idea is that there are no trust-issues from users since the users maintain control over the suitcase as well as physical contact. The risk of theft is also reduced and the environmental detection system is removed which annuls privacy issues. Furthermore, without object detection and obstacle avoidance complex hardware and software architecture are not needed which also reduces the computational power required and increases battery life.

Problem Statement

The first proposed problem statement was: How can we securely make traveling and transporting objects more efficient through autonomous suitcases?

The smart system created should follow its owner within a certain of range of distance, be protected from theft and avoid getting lost.

However, the idea was switched to an engine-assisting suitcase and the problem statement needed to be updated to the following:

How can we make traveling and transporting objects more efficient through engine-assisting suitcases, keeping user's preferences in mind? Since this proposed idea and technology is easier to produce and analyze, it should also be applicable and useful in different environments than airports.

Project Planning

Approach

The original approach for the self-following suitcase was the following:

We aim to design a motorised suitcase that can be configured to follow its owner. First, we will develop a vision for a nominal use case of such a motorised suitcase. From this vision, we will extract user requirements. Then, we will give a high-level architecture showing the different components that will be used (e.g. computer vision, electric drive, etc.). We will do research regarding all these components, gathering the knowledge required to combine them into one device. Finally, we will present a design for a motorised suitcase based on our vision, the user requirements, and the technicalities of the used components used. To deliver an actual working prototype is not the aim, as it turns out that even the companies working on such suitcases (see State of the Art) are having major problems with that, and making such a prototype would require a budget of several hundred euro's. Furthermore, the time available for this project seems too little to build a complete prototype and we probably lack the expertise to combine all the needed systems together. Thus, we only aim at designing the prototype and the hardware/software systems for such a prototype as well as the consequences of such a technology. As the total technology architecture of a self-following suitcase is complex at itself, we expect that the time needed for this project and the time available for this project will match well enough.

However, since the idea was adapted to a engine-assisting suitcase, the approach was slightly changed. Most notably the vision system disappears completely from the suitcase and the control system becomes much easier. However, additional, different sensors were needed for measuring the work done by the user for pulling the suitcase and the computer in the suitcase should autonomously process this input and convert it to the necessary output. Since the new idea is in theory easier than the self-following suitcase, more attention should be given to the accompanying smartphone application as well as a more careful study for the hardware and the movement system. The planning was adapted properly.

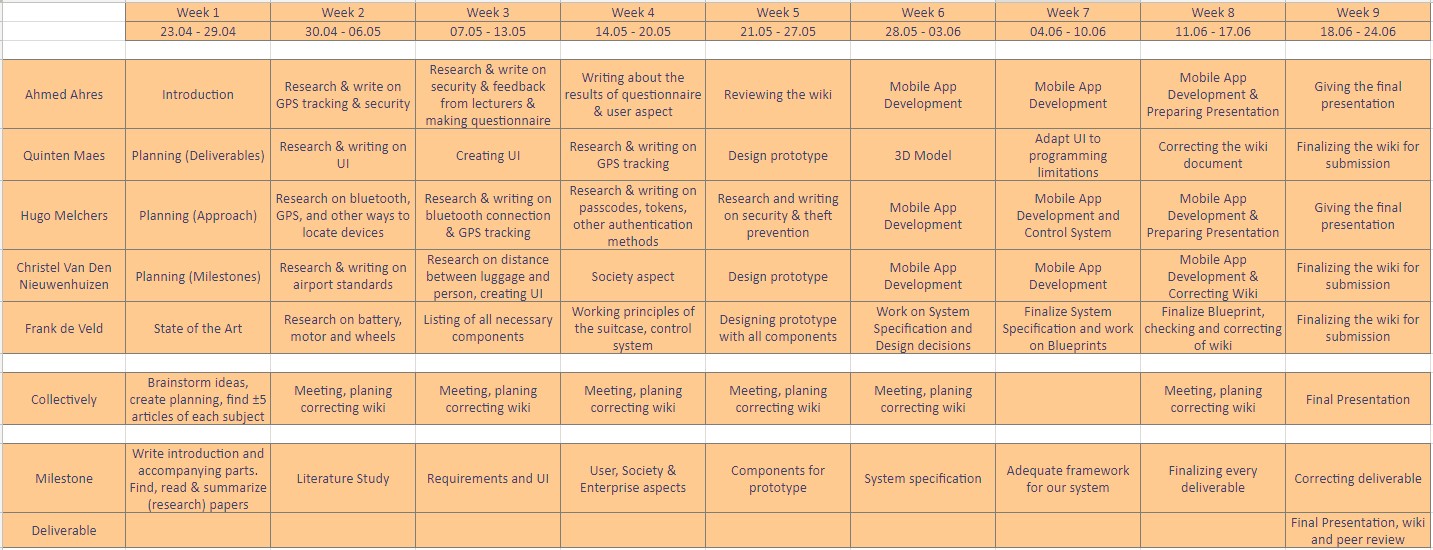

Weekly Planning

Milestones

The following milestones are set for this course. They are shown in the planning aswell.

- In the first week every group member finds and summarizes the articles for their part for the state of the art. The entire introduction and accompanying parts are written.

- In the second week the literature study is done.

- In the third week the requirements and UI design are finished.

- In the fourth week the USE analysis is finished.

- In the fifth week all components for the prototype are available

- In the sixth week the 3D model of the system is finished

- in the seventh week the implementation the wiki should be finished.

- The last milestone is the completion of all deliverables.

Deliverables

For our end deliverables we have to do the following:

- A presentation, which will be held in the last week. In this presentation, we will discuss our findings, present a solution to the problem, and, if possible, give a demonstration.

- This wiki page containing the technology mentioned earlier, taking into account the advantages, disadvantages, costs, and impact of such an implementation. This wiki page also contains an in-depth study of the engine-assisting mechanism as well as a user interface for the desired mobile application, making all of it a framework to develop such a system.

Users

In general the users of this technology are people who regularly have to cover distances with baggage and either have trouble with that or would like to have their load relieved. This mostly covers business travelers, pregnant women, elderly and disabled people. The general area of use would thus be airports, train stations, bus stations, naval docks and urban areas. It is preferable that these technologies are used in relatively smooth and flat terrain. In the case of personal suitcases, the engine-assisting suitcases would be bought particularly by the users. Sections 12.1 and 12.2 detail more about the user needs and user impact.

Requirements

| ID | Category | Requirement |

|---|---|---|

| R1 | Airline regulations | The battery for the suitcase shall be removable. |

| R2 | The weight of the suitcase shall meet the relevant airline regulations, which means it shall be significantly less than the maximum allowed weight. | |

| R3 | The battery for the suitcase shall meet airline regulations regarding material and maximum electric power. | |

| R4 | The size of the suitcase shall meet airline regulations regarding handluggage and hold baggage. | |

| R5 | The suitcase shall adhere to the TSA policies of the United States control border. | |

| R6 | Work reduction | The suitcase shall be able to reduce the amount of work done by the user by 50% at the minimum. |

| R7 | Battery Life | The battery of the suitcase shall have a battery life of up to 10 kilometers of walking distance. |

| R8 | Sensor | The suitcase shall be able to detect the amount of work done by the user with an uncertainty of 5% at maximum. |

| R9 | The suitcase shall be able to detect the location of the user in a radius up to 50 meters via Bluetooth connection. | |

| R10 | Alarms | The suitcase shall transmit an urgent alarm to the user's phone when outside a radius of 50 meters of the user. |

| R11 | The suitcase shall transmit an alarm when the battery life of the suitcase becomes lower than 10%. | |

| R12 | The smartphone application belonging to the suitcase system shall transmit an alarm when the battery life of the phone becomes lower than 10%. | |

| R13 | Mobile Application | The smartphone application belonging to the suitcase system shall be free to download. |

| R14 | The smartphone application belonging to the suitcase system shall be available on the Android Store. | |

| R15 | The smartphone application belonging to the suitcase system shall be available on the Apple Store. | |

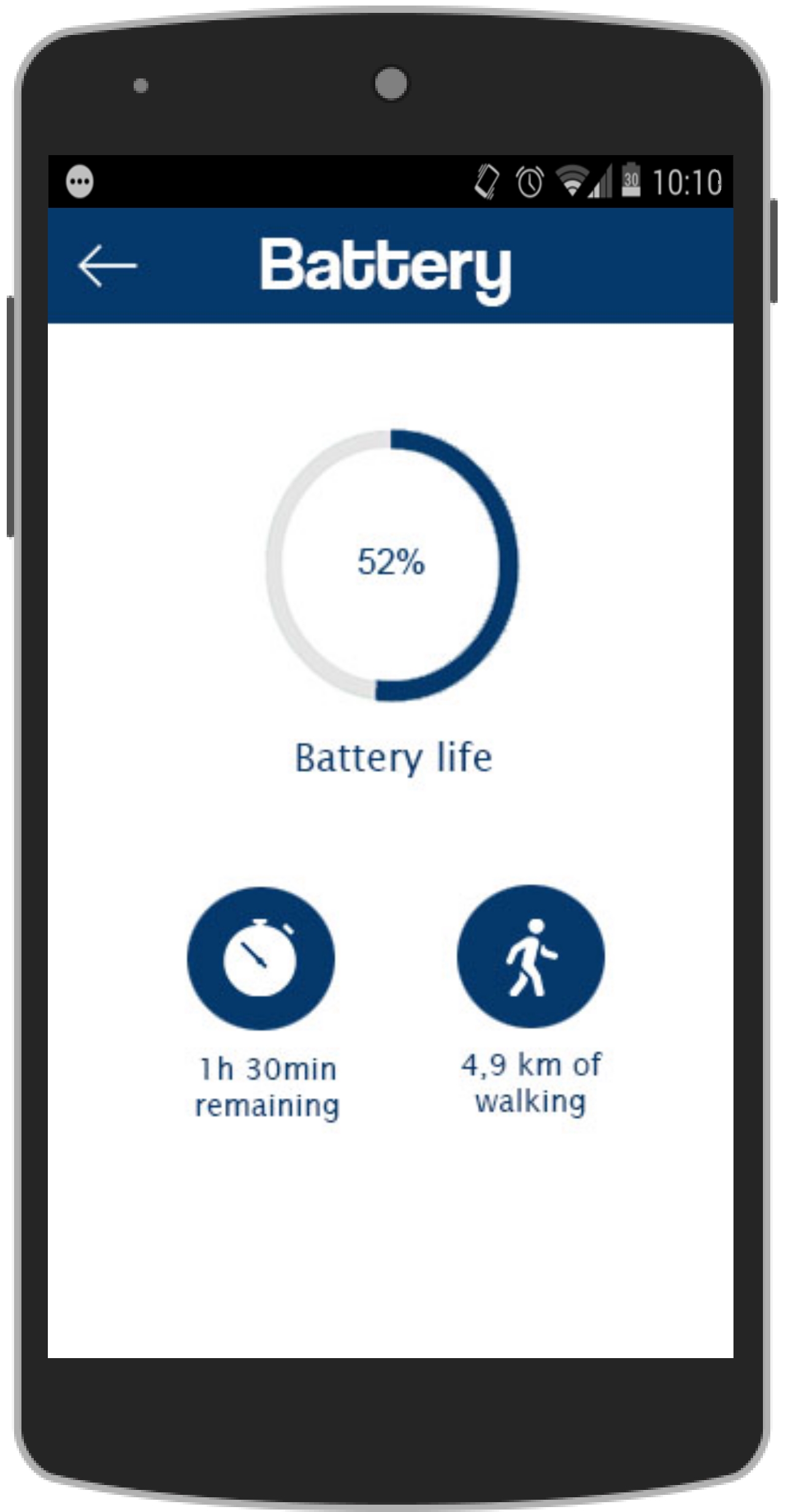

| R16 | The smartphone application belonging to the suitcase system shall display the weight of the suitcase. | |

| R17 | The smartphone application belonging to the suitcase system shall display the (remaining) battery life of the suitcase. | |

| R18 | The smartphone application belonging to the suitcase system shall display the remaining walking distance of the suitcase. | |

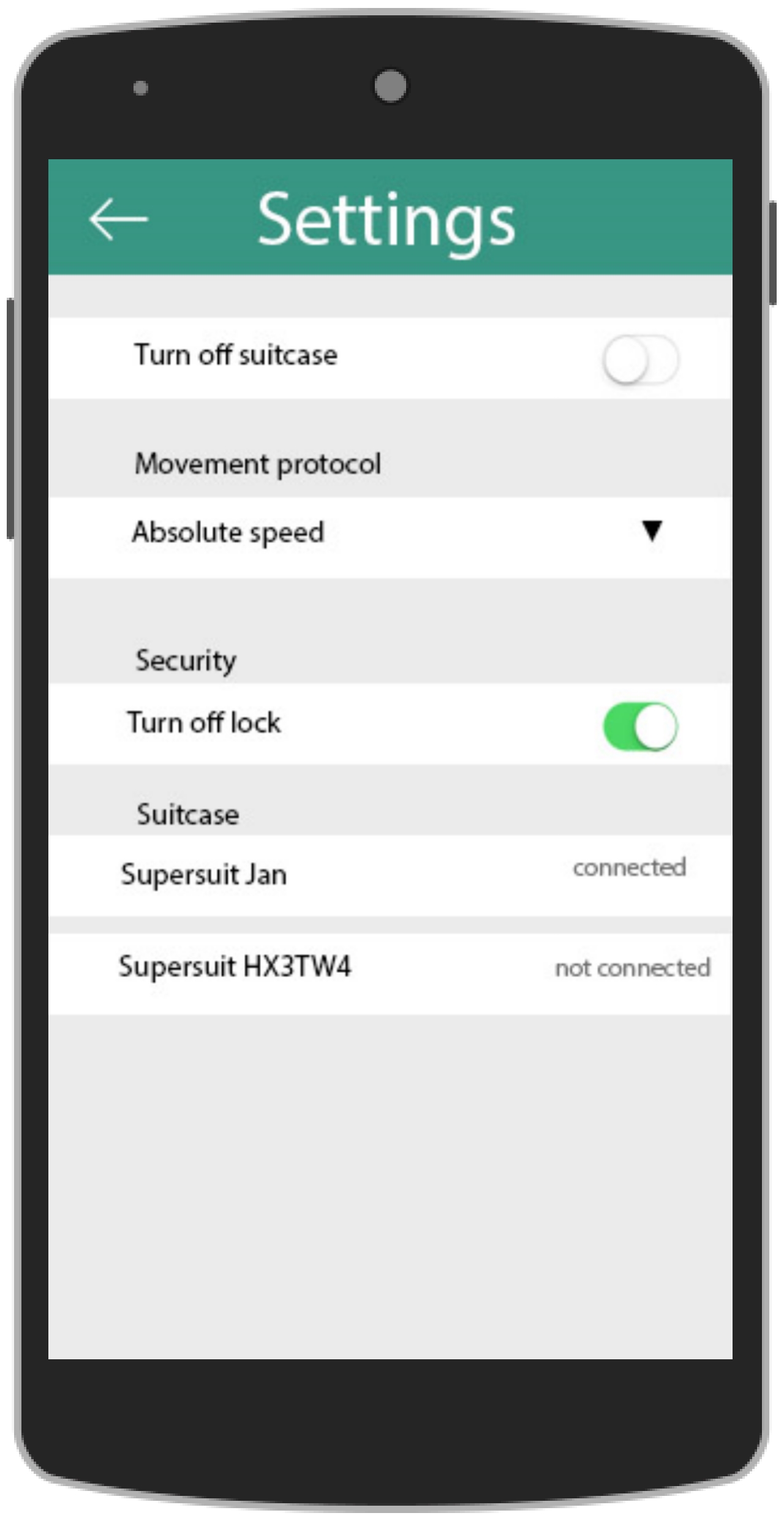

| R19 | The smartphone application belonging to the suitcase system shall lock and unlock the suitcase. | |

| R20 | The smartphone application belonging to the suitcase system shall (dis)connect from and to multiple suitcases. | |

| R21 | The smartphone application belonging to the suitcase system shall turn the suitcase on or off. | |

| R22 | The smartphone application belonging to the suitcase system shall configure the movement protocol of the suitcase. | |

| R23 | Portability | The suitcase shall have both an on mode and a manual mode in which the user pulls the suitcase himself without assisting. |

| R24 | Location | The smartphone app belonging to the suitcase system shall allow the user to access the location of the suitcase. |

| R25 | Costs | The cost of the final product shall not exceed 700 euros. |

| R26 | Materials | The suitcase shall be made out of sturdy and shock-damping materials. |

State of the Art

Self-following suitcase

So far, a few companies have already tackled the case of self following suitcases. At several events, such devices have been shown or demonstrated, but so far none have been sold to private individuals. The companies currently working on a self following suitcase are:

- Olive robotics owned by IKAP Robotics from Iran (http://oliverobotics.com/)

- Travelmate robotics from the United States (https://travelmaterobotics.com/)

- ForwardX from China (https://www.forwardx.com/)

- Cowarobot owned by LeMoreLab from China (http://en.cowarobot.com/en/r1/robotics.htm)

- 90FUN owned by Shanghai Runmi Technology Co., Ltd. from China (https://www.90fun.us/puppy1)

- NUA Robotics from Israel (http://unbouncepages.com/nuarobotics/)

It is important to note that all of these companies, with the parent companies included, have been founded in the previous 3 years. Two of these companies, namely Travelmate and Cowarobot, needed crowdfunding from the crowdfunding website indiegogo.com in order to be able to produce their suitcases, Travelmate even needed two (https://www.indiegogo.com/projects/travelmate-a-fully-autonomous-suitcase-and-robot, https://www.indiegogo.com/projects/travelmate-a-fully-autonomous-suitcase-and-robot--2#/comments and https://www.indiegogo.com/projects/cowarobot-r1-the-first-and-only-robotic-suitcase). Both companies had delivery dates around end 2016 / begin 2017, but both experienced production delays and have not yet delivered the suitcases to their customers. Furthermore, Travelmate has doubled to tripled their prices compared to their original plan (€400 to €600), which was comparable to the price of the one from Cowarobot. Nevertheless, both companies received an overwhelming amount of support from their backers; 400% of the necessary funds was received by Cowarobot and 1600% of the necessary funds were received by Travelmate. The other four companies do not give specifications on either the release date or the price, only NUA Robotics and ForwardX hope to release it at the end of 2018.

It is also interesting to look at the specifications of all these self-following suitcases. Due to airline regulations, most of the companies have a removable battery for the suitcase or aim at having that implemented. Not all companies give specifications on the battery, but most seem to have a Lithum-Ion battery. ForwardX also gives specifications on the capacity: 96 Wh, which meets IATA standards for carry-on luggage. For finding the owner of the suitcase, all companies either have a Bluetooth connection between the suitcase and the smartphone of the user or a Bluetooth connection between the suitcase and an additional smart wristband the user needs to wear. Some companies also use GPS or 3G/4G systems for location detection. The speed of the suitcases varies; for example NUA robotics is only capable of letting the suitcase go 5 km/h while 90FUN promotes a maximum speed of 18 km/h. All suitcases can ride at walking speed however. At last, the sensors for scanning the surroundings differ per company. NUA Robotics and Olive Robotics use a (stereoscopic) camera, ForwardX uses an ultrasonic sensor, Cowarobot a combination of both, while 90FUN and Travelmate don't appear to use an environment measuring sensor.

Moreover, five of these six companies claim to have made the first self following suitcase; only ForwardX is not claiming this. Additionally, NUA Robotics is a very small company and the company does not look very professional. To summarize; there are several companies currently working on the idea of a self following suitcase and they are at varying stages of releasing the technology in form of a product, but it seems most of the companies are too optimistic or have run into some issues and none are delivering yet. However, since the companies are already promoting their idea, there are also numerous responses from potential buyers, both negative and positive. This is a very important source of feedback, since this technology is largely based on the users and their preferences. The most important positive remarks are:

- It is an innovative idea, meaning that certain groups of people will be interested in it in any case

- It is efficient

- It can help disabled people, elderly and pregnant women to transport their suitcases without health risks

The most important negative remarks or fears are:

- It could be stolen easily

- It could be vulnerable to hacking

- The weight could become too high, since the allowed weight for hand luggage is limited

- The size of the batteries might be too high, since the guidelines for batteries on aircraft are strict

- Terrorism could become easier

- It might not useful enough for the target group. This can of course be avoided by searching for other applications, such as aiding elderly or disabled people and improving efficiency in work environments.

It is important that these subjects are adequately thought of in the design of such a suitcase.

However, the case of self following trolleys does not seem to have been explored yet. One device which resembles this idea is the Stewart Golf X9 Follow (https://www.stewartgolf.co.uk/trolleys/x9-follow/), a self following golf cart and another device is a prototype of a self following shopping cart (http://www.technion.ac.il/en/2014/11/a-shopping-cart-that-follows-you/). The golf cart seems to be the only one of the products listed in this section which is actually for sale. Thus, no self following trolleys have been made for airports, retail stores, train stations or other places where a lot of products need to be moved. Since the golf cart is the only actual product resembling the technologies aimed for in this product, it is interesting to investigate how this company has approached the problem of self-following trolleys. The golf cart uses Bluetooth and a separate remote which the user should keep with him and the range is 50 meters. The cart rides a few meters behind the user when on ‘Follow-mode’, but apparently it sometimes ‘chases rabbits’. The battery life is 25 to 30 holes, which means that it last a few hours long. Furthermore, it has downhill braking and an integrated stabilizer, which are important to have on golf courses. Of course, this machine is only useful for transporting golf clubs and golf accessories.

For the intended devices, several important (software) components and concepts are needed, of which there generally is a lot of research about. The important software concepts are autonomous image recognition, obstacle avoidance, remote tracking, control systems, autonomous driving and Bluetooth/GPS connections. Hardware subjects that are relevant are battery efficiency, the most optimal motors and wheels, Arduino connections and battery life. Furthermore, there are general subjects like privacy, security, user preferences and (airport) regulations.

Engine-assisting suitcase

Some of the information on the self-following suitcase is actually still useful when researching an engine-assisting suitcase. Most notably this includes most of the hardware and specifications, most of the applications for which the system is used (including the applications for self-following trolleys), the issues the companies working on the self-following suitcase encountered, and very importantly the feedback given by users on the idea of the self-following suitcase. As it turns out, most people are still afraid of either a malfunctioning robot or theft, both resulting in the loss of the luggage. Another frequent remark was that the self-following suitcase formed either a too complex solution to a problem or a solution for a problem that did not exist. Of course, disabled, pregnant or unfit people are then disregarded, but it is an important remark. The idea of an engine-assisting suitcase largely solves these important issues, as well as the increased chance of terrorism and it helps a little with the problem of weight, as less hardware is needed. Additional important things to research next for this new idea are the concept of electrical bicycles which resemble this, other applications of engine-assisting robots, user's preferences through a questionnaire and how to incorporate a smartphone application with Bluetooth connection in such a system.

Electrical Bicycles

An interesting application that uses similar technology is the electrical bicycle and it is useful to get more information about this technology. The basic idea is that the rider input from the pedals influences the motor and via this the drive wheel of the bicycle. If the user is still able to have manual control over the bicycle, this system is a parallel hybrid system. In the case of a suitcase, the rider input from pedals is changed to input from the smartphone application and the pull of the user to the suitcase. In bicycles, both brushed DC motors as well as brushless DC motors can be used and the main other components are just gears, hubs, rotors and rods. There are generally two types of electrical bikes; one in throttle mode in which you can set the amount of power the battery supplies with a throttle on the bicycle handles (like a scooter) and one in pedal-assisting mode, in which the battery helps you with pedaling. This last 'pedelec'-system comes in two varieties: one with a torque sensor pedal assist which measures the amount of power you deliver and emulate a certain percentage of that, and one with a cadence sensor pedal assist which supplies a constant amount of power which the user can select beforehand. [3]

A fairly large difference in electrical bicycles and the intended suitcase is the battery used, since most electrical bicycles use either Lead acid or NiMH batteries. Both are mostly suitable for big devices which should deliver a lot of power and these are also banned by most airlines due to safety regulations. Luckily Li-ion batteries will probably be perfectly able to provide the energy needed for such systems.

Airport Regulations

There are several airport regulations when it comes to luggage weight, size and type of battery. Airlines are already putting a ban on several of the already existing "smart" bags, because they do not meet the requirements of the airlines. [4] Which indicates the importance of these regulations when making a new smart luggage robot.

Handluggage

- 1 item of hand baggage, max. 55 x 35 x 25 cm (21,5 x 13,5 x 10 inch)

- 1 accessory, e.g. a handbag, briefcase or laptop, max. 40 x 30 x 15 cm (16 x 12 x 6 inch)

- Total weight max. 12 kg (26 lbs).

Check-in bagage

- 1 item of check-in baggage*: L + W + H max. 158 cm (62 inch)

- Total max. 23 kg (50 lbs).

Battery regulations

- Lithium Ion ≤100Wh

- Lithium Metal ≤ 2g

Research articles, patents and other relevant sources

A list of relevant sources (scientific papers and patents) follows underneath:

- Patent for self-following vehicle. This patents is actually pretty short and concise. It refers to other patents as well; it combines several systems into the concept of a target following devices. These systems are: a frame with a front and rear side, wheels, a driving system for wheels, a control system, a remote target unit and a stereoscopic detection system. [5]

- Patent for a small DC motor. DC motors have of course existed for a long time, but this patent is specifically about a mini-sized DC motor. The important components of the DC motor are: a motor frame with a cylindrical portion with constant thickness, field magnets and a minimum sized air gap between the magnets and the frame to be able to rotate the armature assembly. [6]

- Research paper on the design and implementation of a mapping robot with omni-wheels and a Raspberry-Pi. While the aim of this robot is different than in this case, the general architecture of this robot is still useful. Some requirements that are overlapping are: lightweight, movement at walking speed, enough space for sensors and electronics and relatively cheap materials. It was decided that four omni-wheels would be used for their mapping robot with one electric motor on top of each, as well as two double sided L298 motor drivers, an Arduino based controller, a Raspberry Pi as on-board computer and a Li-Pol 7.4 V battery as power source. The sensor that has been used is an ultrasonic HC-SR04 distance sensor. The reason why this article might be useful for this project is their conclusion that it is perfectly possible to create a robot with very general components which aim resembles the aim pursued in this project. The major difference is the weight it should handle and the autonomy of the robot, which can be tackled by using bigger motors, batteries and a stronger on-board computer. [7]

- Research paper on the power and propulsion system for an autonomous robot. This paper is written about a robot participating in the RoboCup competition, a major robotics competition which has the goal of creating a robot soccer team which should win from the human team in 2050. The competition is attended by hundreds of teams each year and the robots get better each year. In this paper, the optimal energy storage system and propulsion system are researched. It is concluded that a Li-polymer battery of 25.9 V assisted by two Li-polymer batteries of 7.4 V each are the optimal power sources, since the power density is high. For the motor system, two cascaded cell modules for controlling motor speed and power flow control are used with DC-DC converters and a kicker circuit. The motor itself is a permanent magnet DC motor. An important remark made in the paper is that deep discharge needs to be avoided for safety and protection of the system. Thus, a basic voltage needs to be present so that the battery life is extended. Furthermore, for this project it is important that the batteries follow airport security guidelines. [8]

- Research paper on a person-following autonomous trolley. This paper was written about the design of a robot that follows his user using both ultrasonic sensors and Bluetooth connection. The robot also reacts on human speech. The paper is mostly focused on the control style variants for robots. In many ways, this paper resembles this project, since it is about self-following robots used in mainly supermarkets, but use for disabled people, sports and military is also suggested in the paper. The approach of the researchers is different than the approach in this project however, since they consider 3D sensors and image processing not cost efficient. Ultrasonic sensors are used instead. While this can certainly work in supermarkets, it might be more difficult to make it work in busy areas as airports. Furthermore, an important remark is made, namely that GPS might be too unreliable at these distances. The robot made for this research paper mainly has components which are also present in similar robots found in other papers, namely two DC motors, a L289N motor controller, a Bluetooth module, an Arduino Mega on board computer, a 12V battery and regular mini wheels. [9]

- Research paper on a novel object avoidance which is easy to tune and takes into consideration the field of view and the nonholonomic constraints of the robot. Moreover the method does not have a local minimum problem and results in safer trajectories because of its inherent properties in the definition of the algorithm. The algorithm is tested in simulations and after the observation of successful results, experimental tests are performed using static and dynamic obstacle scenarios. [10]

- Patent for an object detection system. The method extracts a first feature vector from a first region of an image using a first subnetwork and determines a second region of the image by processing the first feature vector with a second subnetwork. The method also extracts a second feature vector from the second region of the image using the first subnetwork and detects the object using a third subnetwork on a basis of the first feature vector and the second feature. The three subnetworks form a neural network. [11]

- Research paper on the linear time-invariant control system. The paper considers achievable delay margin of a real rational and strictly proper plant, with unstable complex poles, by a linear time-invariant (LTI) controller. The delay margin is defined as the largest time delay such that, for any delay less than this value, the closed-loop stability is maintained. Drawing upon a frequency domain method, particularly a bilinear transform technique, the paper provides an upper bound of the delay margin, which requires computing the maximum of a one-variable function. [12]

- Research paper on object detection using convolutional neural networks for classification. This paper demonstrates that carefully designing deep networks for object classification is just as important as feature extraction. The paper also experiments with region-wise classifier networks that use shared, region-independent convolutional features. [13]

- Research paper discussing the use of so-called pseudolites (pseudo-satellites) for close-range navigation. Using pseudolites, stationary devices that transmit GPS-like signales, and synchrolites, which rebroadcast GPS signals it receives from real GPS satellites, high-accuracy localisation methods become much faster and cost-effective, most notably Carrier-phase Differential GPS or CDGPS, which reduces the baseline error to just 1 centimeter. Localisation can even be done when fewer than 3-4 independent GPS signals are received, which is not the case when no other signals are received. [14]

- Paper discussing how to achieve high accuracy using indoor pseudolites. Here, a constellation of GPS pseudolites is mounted on the ceiling of a large hangar, a car is fitted with antennae, and both run custom algorithms to determine the vehicle's location. The resulting error is less than 1 centimeter. [15]

- Research paper on locating devices indoor using Bluetooth. This paper investigates the possibility of locating a device in a constrained environment using only Bluetooth. While this is possible, it requires many measurements to be taken of the Bluetooth signal strength from the `lost' device, while holding the receiving device (in this case, a smartphone) at specific angles and then move in the estimated direction of the lost device. This way, the location of the device can be reduced by a factor 4 with each measurement. [16]

- Paper discussing Bluetooth beacons and a concept called stigmergy to locate devices indoor. Here, Bluetooth beacons are placed at known locations, and receiving devices can determine their own location using the received signal strengths from these beacons. In addition, it uses a stigmergic approach in which location estimates are treated like chemical markers (pheromones) in ant colonies, that diffuse over time and affect later location estimates. [17]

- Research paper on localising devices indoors using Radio Frequency and Acoustic Ranging. In this paper, an algorithm is presented that uses Wi-Fi and acoustic signals to locate devices in an office environment. This requires that devices are equipped with Wi-Fi, a speaker, and a microphone. In turn, a localisation algorithm called EchoBeep can locate devices even in an environment with walls and other obstacles that obstruct and reflect signals. [18]

- Research paper on distances between a robot and moving obstacles, such as humans based on the concept of depth space. To avoid obstacles the distance between the robot and obstacle is measured, based on the depth space and using an estimation of the obstacle velocity. [19]

Questionnaire Results Analysis

A questionnaire was created with a total of 10 questions and spread online through social media in order to have the opinion of people worldwide. The number of participants is 100 and from various countries, the majority being from The Netherlands and Tunisia. The following questions were asked:

1. How often do you fly per year?

2. How often do you fly with only hand luggage?

3. Do you have trouble moving your luggage, for example at large distances?

4. In case of a yes, where do you have trouble with when moving your luggage?

5. In case of a yes, do others help you with moving your luggage?

6. Do you fear losing your luggage?

7. How important is the weight of an empty luggage for you when buying the suitcase?

8. Is it difficult for you to adhere to the maximum weight for your suitcase?

9. What functionality would you consider useful on a ‘smart’ suitcase?

10. Would you buy a suitcase with these functions?

Analysis of the results

Each question had multiple answers, most with only one correct answer except question 9 which had multiple possibilities along with a field Other in order to have more insight on people's opinion.

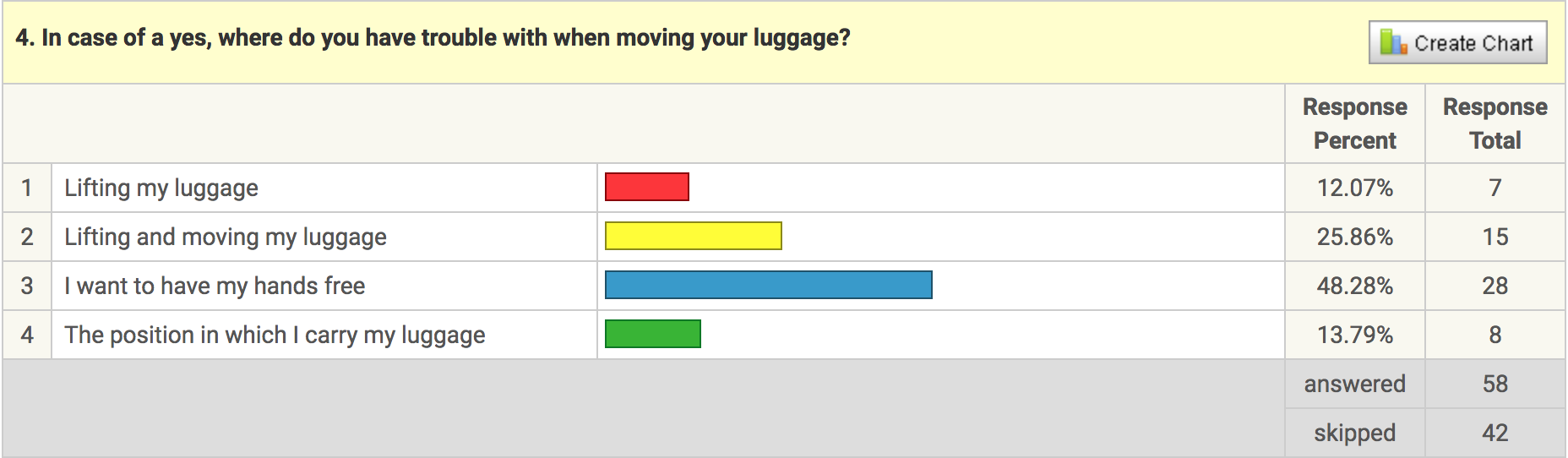

The most interesting questions to analyze are questions 4, 9 and 10. According to the data, it seems that when people do indeed have trouble with moving the luggage in long distances, they would like to have their hands free. The following image shows the results:

Moreover, question 9 also contains extremely interesting information: it seems that GPS location, smartphone connection and self-following are the top answers. Furthermore, in the Other field, 13 people added suggestions in which 6 are about displaying the weight of the luggage in the mobile application. The following image shows the results:

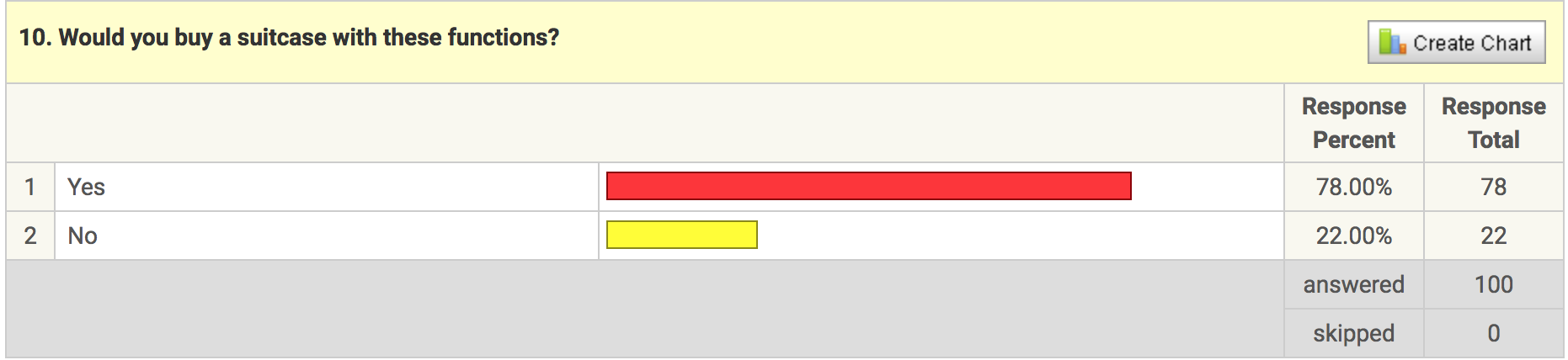

Last but not least, question 10 shows that by adding these features, 78% of the users are willing to buy the suitcase. The following image shows the results:

Conclusion

It goes without saying that the results are promising, showing what people from different cultures (mainly Europe/North Africa) think of such a concept. According to the data, it seems that a hand luggage equipped with GPS tracking and a smartphone application, which also makes it easier for the users to move it around would lead to the users buying it. The data from the questionnaire will be taken into account in deciding which features to add but also in the design of the suitcase itself.

Hardware & Design

One of the challenges of this project is to measure the amount of work done by the user in pulling the suitcase and converting this into motor output voltage. Two relatively easy systems exist for that, with one system measuring pulling force in the handle of the suitcase and another system in the wheel axis measuring the torque of the wheels when pulling the suitcase. The system is the handle is easier to implement while the system in the wheel axis is more accurate. The handle system is less accurate since it has to convert the pulling force to forward speed when the user wants the motor to produce a constant speed. However, in order to do this, the angle between the handle and the ground needs to be known, which varies per moment and per person. Also, when the user wants a certain relative amount of work to be done by the motor on the other hand, the system needs to convert the pulling force to a certain amount of motor power. This can be rather inaccurate, so another system in the wheels for measuring torque. This is a lot more accurate since it measures the actual forward speed of the suitcase directly but it involves also some additional instruments. However, since the handle system only really involves a basic electrical circuit (it can function as a weight measuring system as well, more about that later on) it is no problem to implement that as well.

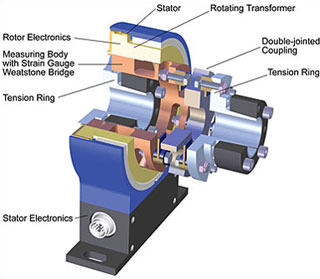

Torque sensors

The most reliable way to let the motor produce a certain relative amount of power is to measure the torque in the wheels when the motor is still off. With the smartphone application, the user can select the amount of work wanted to have relieved and the torque sensors measure the torque on the wheels. The sensors send a signal to the computer system in the suitcase and depending on this the motor generates an amount of torque itself. Then, the sensors again measure the torque and compare it to the necessary amount of torque, so it checks whether the relative amount of work done by the motor is the right amount set by the user.

When talking about torque it is important to understand the difference between dynamic and static torque. Dynamic torque is torque which changes over time, so there is an acceleration present, while static torque is constant over time. In this case it is easier to talk about static torque; the sensors measure the torque on specific times and adjust the motor speed to that. Most of the times the speed of the user plus suitcase is constant anyway, so while it would be more realistic to treat the torque in this case as dynamic, it doesn’t add a lot to the system and dynamic torque sensors are a lot more complicated. Thus, a static torque sensor would be most useful. [20]

There is another important distinction to be made in the field of torque sensors and that is the difference between reaction torque sensors and rotary torque sensors. Reaction torque sensors are not quite useful to this project since the rotation here is limited to 360°. Rotary torque sensors are mounted underneath the device under test and have no rotation limitation. The actual measurement of the torque is done by either strain gages in a Wheatstone bridge circuit, optical speed sensors or a combination of both. Sensor input is recorded in Volt and transmitted to the onboard computer. [21]

However, another useful function is to let the motor produce a constant, absolute amount of power. A sensor is needed for that that measures whether the user is pulling the suitcase, since the suitcase should not let the motor run without user's assistance. In electric bicycles there are cadence sensors which can measure whether the user is cycling on the pedals or not. In the suitcase it would be sufficient to just use a combination of the torque and the weight sensors; if both are measuring movement, this means the suitcase is in use and that the motor should produce a constant amount of power if that mode is selected. If only the weight sensor measures movement, it is probably just lifted from the ground and if only the torque sensor measures movement, this also means the suitcase isn't actually moving. Furthermore, if the suitcase is both lifted up and the wheels are turning, the motor would produce power, though this isn't really a problem and such a position would not be maintained over an extended amount of time.

Weight sensors

It is quite convenient and not very complicated to implement a weight-measuring device into the smart suitcase. A simple way of measuring weight is by using a spring like in a normal kitchen scale. This method uses Hooke’s law [22] to give a good approximation of the force on the weight scale and thus of the weight of the object on the weight scale. It doesn’t have to be a digital weight scale in this way, as the output can be given on an analogous scale and no electricity is needed for that. The downside is that there are some inaccuracies; the calibration may not have been done properly, Hooke’s law is only a linear approximation, the spring used may wear over time and it is not easy to read the output accurately. Furthermore, when using electrical components like in the suitcase, it is easier to just switch to the digital variant, which does not use spring but rather an electrical circuit named the ‘Wheatstone bridge’ which is known for its extreme accuracy and is used in a variety of applications. [23] . A Wheatstone bridge consists of a number of resistors, usually four, of which two are known are known and constant, one is adjustable, and one is unknown. This unknown resistance varies when force is applied in the right way to the circuit. By adjusting the adjustable resistance and using a galvanometer, it is possible to find the value of resistance in the adjustable resistor in order to let the galvanometer show a zero reading, meaning equilibrium. Using calibration this value of resistance can be used to calculate the force applied and thus the weight. This calculation as well as some needed noise-filtering is done by a small computer that fits into the weight sensor. Digital weight sensors like kitchen weight scales use such methods and it can easily fit into the handle of a suitcase.

Batteries

Before looking into the subject of batteries more deeply, first the findings on airline regulations need to be recapped, since this has the highest priority for the actual product. Batteries that are forbidden here are completely out of the question. Firstly, any batteries in any device need to be removable from the device and there are very strict battery regulations for checked luggage. The types of batteries that were allowed were:

- Dry cell alkaline batteries (AA, AAA, C, D, 9-Volt, button cell batteries)

- Dry cell rechargeable batteries (NiMH, NiCad)

- Lithium ion batteries (Up to 100 Wh, 101-160 Wh with approval)

- Lithium metal batteries (Up to 2 grams of lithium per battery)

- Nonspillable wet batteries (Up to 12 V, 100 Wh per battery)

In most of these cases the amount of batteries which can be transported is limited, sometimes to two, sometimes to more than twenty. The most important battery type in the list is the type of Lithium-ion batteries, since they are used most in medium-sized robots. Most laptop-batteries are allowed for example and they can roughly deliver the same amount of power as is needed in a smart suitcase.

Some types of batteries that are not allowed or for which sharp restrictions exist are:

- Lead acid batteries

- Car batteries

- Industrial batteries like absolyte, NiFe-batteries or steel case batteries

- Nuclear batteries

Most of these batteries are either too large or too heavy for the intended purpose anyway. Most of the times, such batteries are shipped or transported overland rather than via airplanes.

Then there is the option between one or multiple batteries. The main reason for the difference is that difference parts of a robot need different voltages: sensors at approximately 5V, motors at 9V-12V but servos at 3V-6V and other electronics at 9V-12V. When using a simple design, it might be better to just use different batteries at different voltages for the different components. However, all these batteries need to be removable and need to be removed at border control, as well as all the batteries need to be recharged separately. Furthermore, using microcontrollers the voltage can be adjusted. Thus, in this application it is more useful to use one main battery.

A popular choice is the lithium-polymer battery or LiPo for short. It has a rather high specific energy and higher than comparative batteries. For the same amount of energy, the battery is thus lighter. Since weight is an important feature in the suitcase, this is very useful. Furthermore, they are relatively unconstrained and somewhat flexible. Some laptops use LiPo batteries as well, as well as some electric vehicles. However, LiPo suffers from the same risks as other Lithium-ion batteries, namely explosion and fire hazard. These can happen when the battery is overcharged, is either very hot or cold, when there is a short circuit or when it is penetrated by a sharp object. The electrolyte then leaks, causing explosions or fire. Several instances of this happening have been recorded. [24] This risk should of course be minimized and a number of precautions are made on the more advanced batteries, such as over charge protection, EMF protection, over discharge protection, thermal effects protection, safe reset mechanisms and general over current or over voltage protection. These are called ‘protected batteries’.

Wheels

The initial idea for a self-following suitcase was to put four omni-wheels under the suitcase which were motorized individually. Research on state-of-the-art showed that some airlines had prohibited self-balancing devices like segways for transportation on airplanes and that potentially more had this intention. It was thus impossible to make an autonomous device that had just two wheels, since it should be able to balance itself when in autonomous mode. However, when the switch to an engine-assisting suitcase was made, some assumptions changed. First of all, the user always has a hand on the handle of the suitcase and thus always has a physical connection with the suitcase. A consequence of this was that the user would automatically provide the balance for the suitcase, as the user is prone to do with normal suitcases anyway. The option of two-wheeled suitcases was then open again. Additionally, torque sensors were needed for the wheel system. It is then much easier to actually implement the wheels into the suitcase, rather than have them completely under the suitcase. Furthermore, it is quite complicated to make an engine-assisting robot with wheels that can turn 360 degrees and many errors can be made with this. Lastly, one wins a significant amount of baggage space when the wheels are incorporated into the suitcase itself. Thus, two wheels should be used in this suitcase which are implemented in the suitcase itself. These wheels can be regular robot wheels, though there is the requirement that they can be powered by a motor. Also there is the requirement that they also should be able to work when the motor is switched off, but this is more of a requirement for the motor. There is no need for the wheels to be operated separately, as the suitcase will not be remotely operable or be able to turn on its own. There is also no need for two additional wheels at the other side of the suitcase, as the handle of the suitcase is just on one side and the suitcase will be pulled from one direction only.

Motor

Several different motors exist for robotic applications. The most important are:

- AC Motor

- Brushed DC Motor

- Brushless DC Motor

- Geared DC Motor

- Servo Motor

From these, the AC motor is definitely the least convenient. Most electronics for robotic application works on DC (direct current) and so do most batteries which can be used for robotics. Furthermore, most AC motors are rather big and way too powerful for the intended purposes. Secondly servo motors are not particularly useful either. Most of them are limited to 180 degrees of motions and are not strong enough to move a load of 10 kg for an extended period of time. This leaves DC motors, but there are some varieties in this category. [25]

After some reconsideration, it seems most advisable to use brushless DC motors with additional gears for lower power levels. The main difference with brushed DC motors is that these motors produce an audible whine sound from the commutator brushes, that brushed DC motors also have a lot of electrical noise which can damage electrical components and that brushed DC motors are not very efficient. Brushless DC motors don’t have these problems. However, brushless DC motors need a separate motor controller and are slightly more complicated to operate. Additionally, a number of gears is used to easily switch between lower and higher speeds. The plain brushless DC motor doesn’t operate too well on low speeds. A simple gear construction can be used to switch between speed and torque. [26]

The basic working principles of a brushless DC motor are fairly simple. There is only one moving part and that is the rotor. It is rotated by energizing the windings inside or outside of the rotor in a specific sequence. The idea is to constantly attract the north and south poles of the rotor to the direction the roto should rotate. Therefore, the north and south poles of the windings need to switch constantly. In this manner, the mechanics are similar to that of a particle accelerator. It is then also important to incorporate acceleration in the system. The idea is that the rotor spins at a certain constant speed if the magnetic poles of the external windings switch periodically. If this period is shortened, the rotor will spin at a higher speed and vice versa. The process of shortening the period causes acceleration of the rotor. Control is also needed in this case, more than in comparative motors. Most brushless DC motors use a so called ‘Hall Effect Sensor’ or an optical sensor to detect the position of the poles of the rotor.

Actually, most brushless DC motors are a combination of several AC motors. The system produces an AC power output of a certain phase from an DC power input from the battery and this rungs the brushless motors by sending this sequence of AC signals originating from the electronics speed control’s circuitry in the onboard computer. All of this combined results in no sparks, long lifetime of components, few noise, few electrical noise, high efficiency and high maximum speed.

List of components

- Two LiPo batteries

- Two motor-powered wheels

- Two brushless DC motors with an additional gear box

- Robot motor controller

- Arduino or RaspberryPi as microcontroller

- Wires

- Static torque sensors

- Weight sensor with Wheatstone Bridge

- Bluetooth sensor and transmitter

- GPS sensor and transmitter

- Battery life sensor

- Strong polymer case

- Extensible handle

Just some notes, need to be elaborated: Idea: Suitcase goes 3 m/s, so the rotor has a specific rotational velocity and this is measured by a Hall effect sensor in the motor. The suitcase needs to deliver a certain percentage of the force. The idea is that the motor then gradually takes over this percentage of force from the user, while the speed stays constant and the user gradually decreases his amount of force. However, the problem is that in the current configuration the user is perfectly able to use the suitcase while the motor is off, but when the motor is on the suitcase goes at the speed of the motor, or else speeds the suitcase up or slows the suitcase down. Furthermore, one should be careful for inductance current, unwanted magnetic fields and short circuits. This is probably not a big problem. The force diagram is easy and will be pictured with paint.net soon. However, it may be useful to measure the tension sensors in order to measure the forces component wise and not directly, so that the roll resistance force can be measured.

3D Model

A 3D model of the envisioned system was created using the design decisions stated above.

Software & Technology

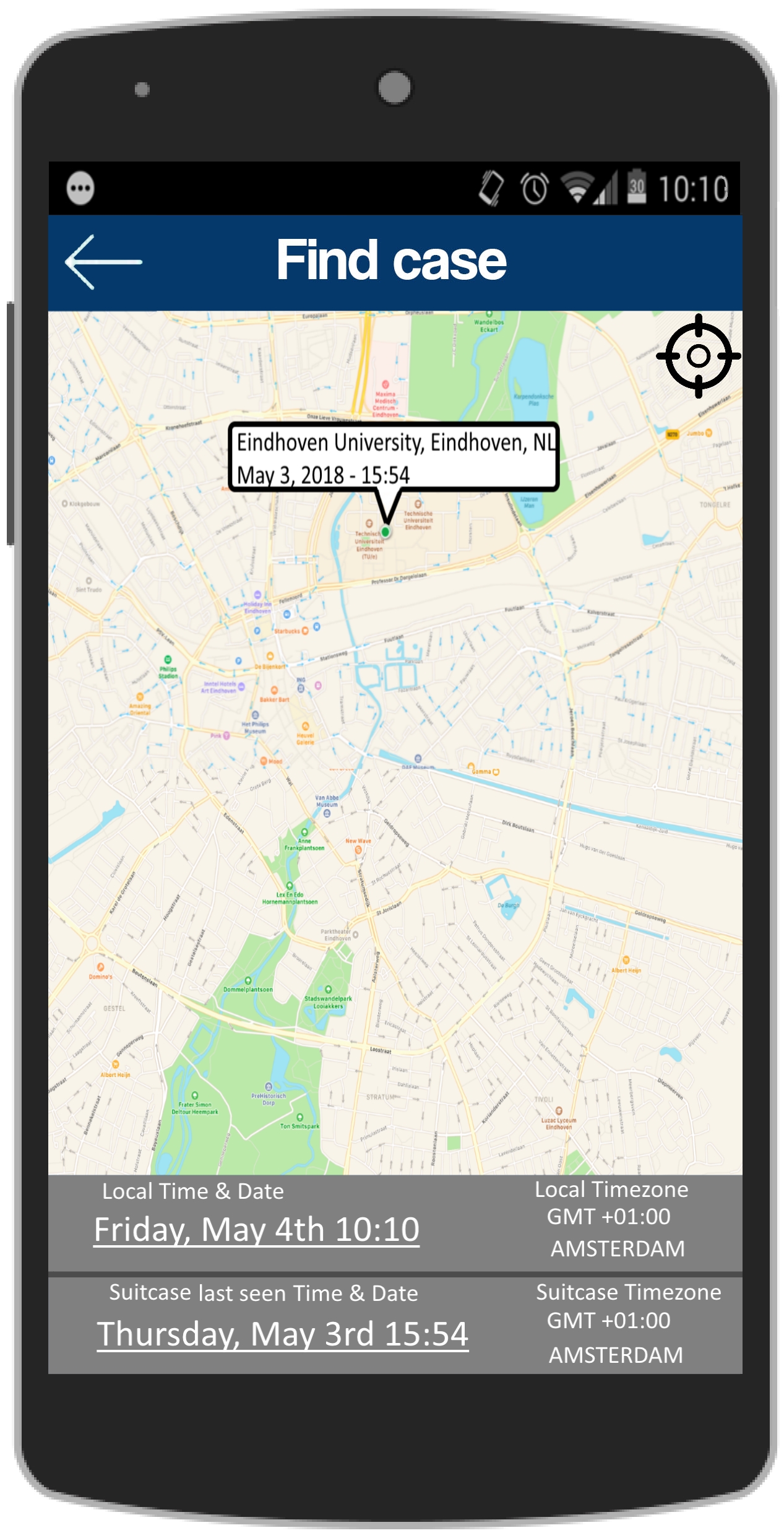

It goes without saying that our system needs multiple technologies in order to be useful for the users and for society. Such technologies include GPS tracking in order for the user to be able to locate his/her suitcase when stolen or lost and bluetooth connection in order to access information about the luggage such as battery life. Moreover, security is of great importance where a fingerprint lock can be added as a two-factor authentication in order to ensure that no one can stole the content of the suitcase.

GPS Tracking

In order for the user to track the position of the luggage at all times and locate it if the system gets stolen or lost, a Global Positioning System (GPS) tracker is used. This technology uses a receiver that communicates with satellites to determine global position that is accurate to up to 5 meters[27], which is enough for a user to see the suitcase. A GPS tracking system uses the Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) network. This network incorporates a range of satellites that use microwave signals that are transmitted to GPS devices to give information on location, vehicle speed, time and direction. So, a GPS tracking system can potentially give both real-time (active tracking system) and historic navigation (passive tracking system) data on any kind of journey. The control of the Positioning System consists of different tracking stations that are located across the globe. These monitoring stations help in tracking signals from the GPS satellites that are continuously orbiting the earth. Space vehicles transmit microwave carrier signals. The users of Global Positioning Systems have GPS receivers that convert these satellite signals so that one can estimate the actual position, velocity and time. For our purpose, we are more interested in real-time data and thus the active system as the user wishes to locate the suitcase in the current time.

This data can then be sent to the mobile application on the user's phone.

Bluetooth Connection

During normal use, the user must be able to interact with the suitcase. An example of such an interaction is the user monitoring the amount of charge that remains in the batteries. Many of the features described under the section 'security' will also require that the suitcase and its user can communicate with each other. For this, we will use a Bluetooth connection between the suitcase and the user's smartphone. The connection will be initialized using a smartphone app, that will be described in further detail under the section 'Mobile Application'.

Our choice to use Bluetooth was largely based on [28], which compares four popular wireless data transfer protocols: Bluetooth, ultra-wideband (UWB), ZigBee, and Wi-Fi. These protocols are compared by transmission time and throughput, data coding efficiency, protocol complexity, and power consumption (both overall and relative to throughput). Wi-Fi and UWB have very high throughputs and equally high power usage, meaning that in our scenario, where the required throughput will not be very high, these protocols are not very suitable. Comparing ZigBee and Bluetooth, the paper notes that the ZigBee protocol is much less complicated, being defined by the IEEE using just 48 primitives compared to Bluetooth's 188 primitives. This would make ZigBee more suitable for devices with little processing power such as our suitcase. However, the power usages of both systems are similar, and Bluetooth consumes significantly less power per Mb of data sent or received. Since both protocols have low throughput (less than 1 Mb/s), this means that Bluetooth may consume less power than ZigBee in our use case. However, as mentioned before, the differences between both protocols in the areas that are relevant to us, are quite small. We elected to use Bluetooth for our suitcase, since this protocol is widely available on smartphones and is already familiar to many users.

A more detailed analysis of Bluetooth's power consumption is given in [29]. This paper gives a detailed method to measure the power consumption of Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) devices. It also uses this method on an example device, namely a keyfob with some buttons, representing a generic device with little processing power that will occasionally transmit and receive little bits of data. It makes the following measurements: a connection event, which consists of a data packet being received, and a response being transmitted, takes between 2.6 and 2.7 milliseconds. This time includes the time it takes for the Bluetooth chip to wake from its sleeping state, receive the message, transmit a response, process the message, and go back to sleep. The average power consumption for one such event is measured to be between 8.25 and 8.53 mA, with 0.001 mA being used when the chip is in sleep mode. The average power consumption with 1 packet being received per second is then equal to 0.0230 to 0.0247 mA, meaning that the device could receive 1 message per second constantly for approximately 400 days when powered by a standard coin-cell battery with a 230mAh capacity. Note that in these tests, the packets sent are empty (e.g. have a full header but empty payload). In practice, meaningful messages with an actual payload would mean that the time to receive, transmit, and process will be higher, and power consumption will therefore also be higher. In our case, the messages should still be small (single numbers representing e.g. battery percentage), so we expect this paper's results to be a good indication of our real-world power usage. Furthermore, the measured power consumption of the Bluetooth chip will then be insignificant compared to that of the electric motors, meaning that 'stand-by' power usage will not be a concern for us.

Calendar

Another feature that can be added is for the suitcase to remind the user to charge the system one day before traveling. In this sense, the suitcase should synchronize with the calendar of the user. In case the user plans to travel the next day, then the mobile application can show a message or notification in the user's phone suggesting that he/she should charge the suitcase. In this way, the user avoids having an empty battery in the airport and can use all the features.

Security Systems

Two-factor authentication: In order to ensure more safety, a two factor authentication can be added to the system. Also known as 2FA, this method is an extra layer of security that is known as "multi factor authentication" that requires not only a password and username but also something that only, and only, that user has on them, i.e. a piece of information only they should know or have immediately to hand - such as a physical token. It is already commonly used in mobile applications such as WhatsApp. When implementing this extra security layer, one needs to take into account the policies in the United States, namely the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) [30] lock in which the US board control should have the possibility of opening the suitcase. In this sense, the system could have a physical lock accompanied with a lock on the mobile application (either pin code or fingerprint). However, in the scenario where the user loses the phone or the phone is turned off, then the baggage cannot be opened until the phone is found or turned on again, which is not desired. Another possibility is to have at all times a fingerprint system on the baggage itself, however this would not allow the United States borders to open the baggage if needed. Hence, we opted for a two factor authentication that would use a fingerprint system on the suitcase along with a TSA compliant physical lock, with the fingerprint system that can be disabled from the mobile application. In this way, the user can disable the fingerprint system when entering the United States customs.

Position Tracking: Using the GPS tracking system discussed earlier, one can always track the position of the system using the mobile application. If for instance a suitcase is stolen in an airport, then the owner can use the mobile application to find the suitcase and ensure that the content is not stolen.

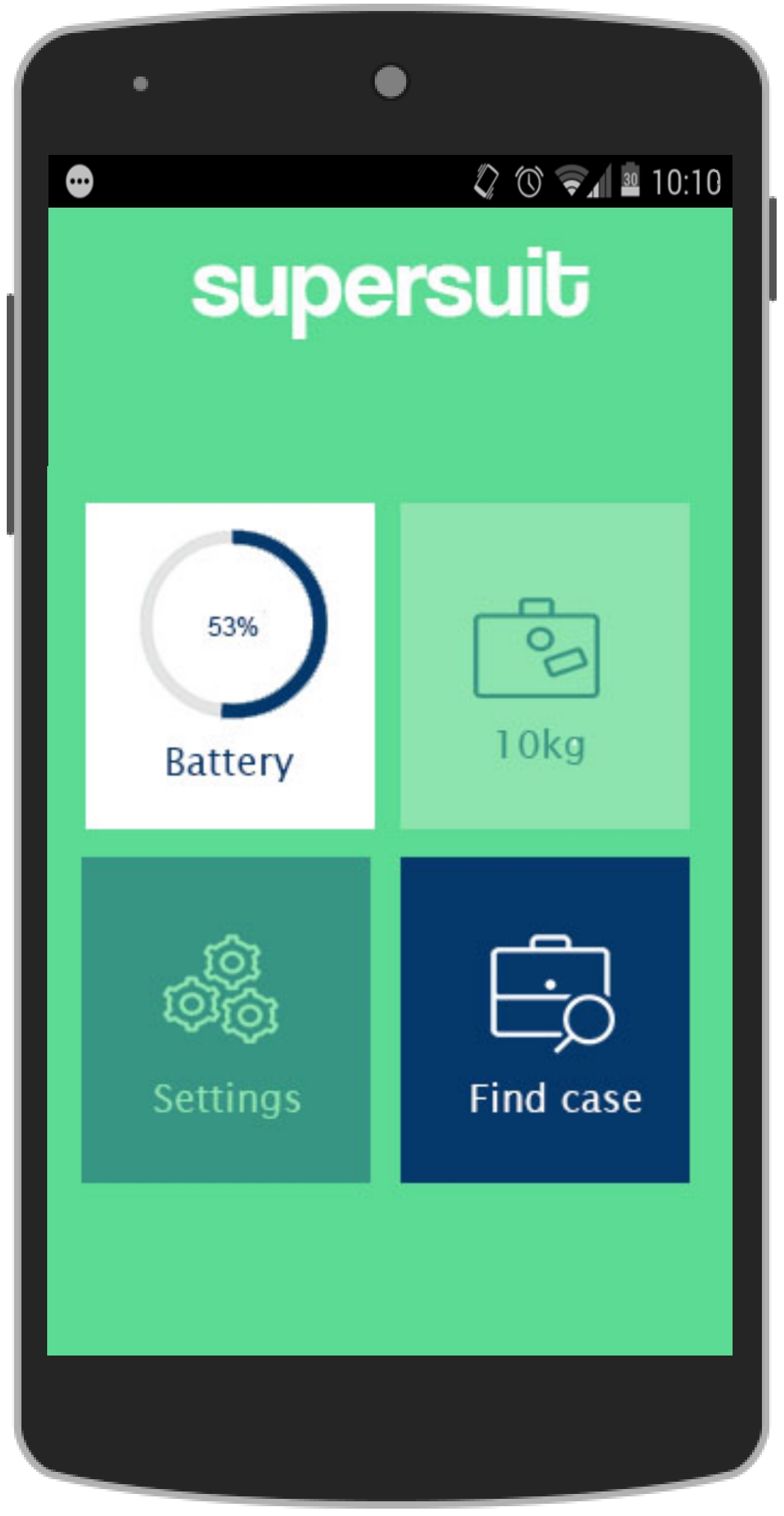

Mobile Application

A mobile application is necessary to accompany the smart suitcase. Even though it does not directly influence the engine assisting part of the suitcase, features such as battery percentage and GPS tracking help users plan their trip and enhance security. These features can either be displayed on an on-board screen or a smartphone application. By using a mobile application, it makes it much easier and simpler for the user to access the informations at all times.

User Interface

Assistance method

For assisting the user in moving the suitcase, we imagine several different options:

1. Firstly, the motors could push the suitcase in the direction measured by the sensors with a constant amount of force. This amount can then be adjusted, e.g. using the app. The main advantage of this method is that it does not require that the suitcase measures the magnitude of the force applied by the user: only the direction has to be known, which helps simplify the sensors as well as the software. It may, however, lead to situations in which the suitcase moves with more force than the user applies, causing it to 'shoot ahead' of the user. When the suitcase is not being moved, it is important that the sensors don't detect 'noise' caused by small disturbances or unevenness of the floor, as this could result in the suitcase moving randomly by itself. One way to prevent this, is to deactivate the motors when the user is not touching the handle. Since there is already a sensor here, this could easily be implemented. However, it would also mean that the user can't push or pull the suitcase without using the handle.

2. A second option is to define the force exerted by the motors to be a certain (adjustable) percentage of the total required force. For example, the user could set the suitcase to always do 70% of the work, with the user only having to do the remaining 30%. This method may feel more 'natural' to the user; for example, if a suitcase with a 10kg net weight assists for 70%, it may feel like it only weighs 3 kilograms to the user. However, it will also require more complicated sensing and software. Specifically, it may prove difficult to measure the torque from the user while the motors are also turning the wheels. Of course, it will also require that the magnitude of the force is known, not just the direction. Furthermore, this method is limited by the maximum torque of the motors, meaning that if the user applies too much force on the suitcase, the torque required from the motors has to be limited in some way, so as to prevent damaging the electronics. In general, this method may prove to be more demanding on the suitcase, since there is no theoretical limit to the amount of force that will be needed.

These two options all have advantages and disadvantages, and requires us to compromise between complexity and user experience. However, we note two things:

- Even when the magnitude of the sensors is required, we expect a modern microprocessor like a Raspberry-Pi or an Arduino to be more than capable of processing these inputs quickly, meaning that the software complexity is probably not a concern.

- Secondly, measuring the magnitude of a force should not be very complicated either, since force sensors and torque sensors are fairly common and widely available.

Together, this means that for the first option, the only significant concern is the maximum load on the engines. Therefore, we propose a third method for assisting:

3. A third option would be to use a combination the above approaches: as the user starts applying force, the suitcase compensates a set percentage of it. As the user's force increases, however, the suitcase's contribution approaches a certain maximum that it does not exceed. This way, the suitcase's behavior is still natural and predictable in most cases, while ensuring that the system is not 'overloaded' in any case. However, the effective behavior is then that the suitcase appears to 'resist' going faster: it will compensate a smaller part of the required force, meaning it will feel heavier. The user will interpret this as meaning they should be going more slowly, which means it's very important that this does not start happening at low speeds.

This last method of assisting looks the most promising to us right now. However, all three options should be experimented with when a real prototype is being developed.

USE Aspects

User Need

The user groups for the above introduced system can be divided into two categories. The primary users consist mainly of any traveller, regardless of the age, gender or ethnicity. However, one could argue that some users are more positively influenced by the system than other, namely pregnant women, the elderly and disabled people. Indeed, pregnant women should avoid lifting any heavy objects [31]. Moreover, the elderly could suffer from back injuries and disabled people have difficulties lifting or moving suitcases. The secondary users are the people that repair such a suitcase, in case of a dysfunction or a broken piece. In this sense, the following needs are important:

Primary users

- Travelers want to minimize the physical effort when carrying a hand luggage

- Traveling can be a very tiring process, either through long flights or multiple transfers on top of physically carrying a suitcase. By having an engine-assisting mechanism, the physical effort done by any person is reduced. This allows for a less tiring traveling process especially for the elderly, disabled or pregnant people. The more helpful the suitcase is in assisting, the better it is for the travelers.

- Travelers want to minimize the chances of having their suitcase stolen or lost

- Having personal items stolen or lost can be extremely frustrating for anyone, regardless of the value of those items. If the traveler has access to the current location of the items at any time, then the chances of being stolen or lost is reduced. Moreover, in the case of a robbery, knowing that the robber cannot have access to the personal belongings would be helpful while the traveler is searching for the suitcase.

- Travelers want to know the weight of their suitcase at all times

- In some situations, the weight of the hang luggage can decide whether the suitcase can be taken with the traveler in the plane or should be in the cargo hold. Moreover, the weight is an indication of how much effort the user needs to put when carrying the suitcase. Therefore, accessing such an information can be helpful for the traveler.

- Travelers want to have access to all the information stated above

- It goes without saying that the traveler wants to access the information such as weight and location in an easy way and at all times.

- Travelers want to afford the system

- The system should not be sold at an extremely high price (> 700 euros) so that the users can afford it.

Secondary users

- The secondary user needs the system to be easily maintainable

- Maintainability should be taken into account during the design of the system. If maintainability is low, it costs both a lot of time and money to fix or improve the system which is a major disadvantage for both the manufacturer and the user. This will decrease the chances of selling the system because it will generate great problems in case the system is down.

User Impact

The impact of the implementation is manifold. Below the different user segments are listed again for the sake of readability.

Primary users: Travelers

- Less tiring traveling process: this is the result of a robust and well designed engine-assisting mechanism within the suitcase.

- Less stolen or lost luggages: this is a result of having access to the location of the suitcase at all times through the mobile application and the ability to lock the suitcase remotely.

- Better organization and prediction on the traveling process: this is the result of having access to the weight of the suitcase.

Secondary: Maintenance / Supplier

- Increase in demand for their services: this is an outcome of the fact that when more people start using the system, mouth-to-mouth advertising and other indirect forms (social media, press among others) will contribute to increasing product awareness.

Society Need

Similarly to the user category, the society has needs.

- Decrease luggage-related injuries

- By assisting in the luggage moving process, vulnerable users such as pregnant women or the elderly have the risk of getting (back) injury reduced

- Create a better and more pleasant experience for people traveling with carry-on luggage

- By assisting in the luggage moving process, traveling becomes less tiring and thus a more pleasant experience. It is believed that there are 8 million people that travel by plane per day [32]. As a result, this means that the experience can be more pleasant for millions of people every single day.

Society Impact

In a fast automating society the need to make our daily lives easier is increasing. Nowadays flying is much easier, cheaper and common for most of the people in western society. As discussed in the introduction the amount of travelers at airports increases every year with millions. The suitcase allows an easier way of traveling for our users. If more people are able to travel or have a better experience when traveling. The total amount of travelers will increase, which has a big impact on society. When the total amount of travelers increases, more facilities are needed due to the increase in tourism, which will lead to economic growth.

We choose to make an assistive traveling suitcase, which will reduce the impact on the way of traveling. A self-following suitcase changes the traditional way of traveling and has therefore a larger impact on society. Since it still has the traditional feeling of traveling, but then with a different product. The way of traveling will not have a large impact on society.

Another issue for society when it comes to traveling with luggage are the amount of luggage-related injuries. In 2015 in the United States there were around 84,000 thousand luggage-related injuries reported. The main cause of the injury were mostly weight-related issues by overpacking of baggage. By moving their luggage people already suffered from shoulder and back pains. [33] The smart suitcase reliefs a part of the weight from the traveling and is a good prevention for potential traveling injuries.

Enterprise Need

Like mentioned before, with the increase of automation in our daily lives, the need to live better whilst also living faster is inevitable. Enterprises play in a large role in this improvement. With regards to the assisting suitcase, travel agencies, airports and bus companies are the ones who could benefit the most. Airports could supply assisting suitcases to frequent fliers, companies or other major customers.

- Automation can lead to more sales

- As automation is taking more and more a importance in the world (self-driving cars, autonomous drones to name a few), automated systems are part of the future's technology and users are keen to buy automated systems to make their daily experiences easier and more pleasurable.

- Automating systems can lead to more jobs

- The engine-assisting suitcases require design, hardware research and development as well as software research and development. All these fields require employees which are mainly engineers, thus contributing to the job market.

- There are more tourists every year

- Since the number of tourists increases every year, companies have more customers and can therefore sell the system to more potential buyers.

Enterprise Impact

The implementation of the assisting suitcase has several consequences for travel agencies.

Airports

- Every electronic device needs be charged at some point in time. Especially whilst traveling, where the possibility to charge any of these devices is far and few between people have the tendency to charge as often as possible. If the assisting suitcase becomes a standard for frequent fliers this would mean that they will not only try to charge devices like their mobile phones, tablets and laptops but now also a suitcase. A consequence of this additional device that needs electricity is power sockets at airports become more and more crowded as they are in high demand. This could lead to congestion in certain areas, even so much so that it hinders other travelers to reach their destination in time.

- With the assistance of the electronic suitcase travellers are able to get from point A to B faster. As the lugage that they now have with them supports them as they walk along. This decrease in travel time, for example between gates, could mean that airlines can schedule their flights closer to one another as they have to leave passengers less time to get there between flights since they most likely will be there quicker.

Future Developments

There are a number of ways in which the technologies discussed here can be extended and improved upon. We will talk about some of these ways here.

Security

One possible feature that could be improved on is security: the suitcase could for example be locked electronically using e.g. facial recognition. This would also be a considerable extra cost, so an alternative approach could be to use the smarthone app to unlock the suitcase. Most modern phones already have biometric security systems, which could then be used as-is instead of putting this technology in the suitcase itself. However, this would also mean that when a user loses their smartphone, they also lose access to the contents of their suitcase, which is a considerable risk when travelling. It would even be possible that the user puts their phone in the suitcase and locks him/herself out of their suitcase.

Usage in different contexts

The technology to amplify a user's efforts to help move heavy objects can be extended beyond the use of suitcases. For example, the same methods could help warehouse employees move heavy trolleys. Furthermore, this could prove to be exceptionally useful for wheelchairs, not only making them easier to push from behind, but also helping the person in the wheelchair move by themselves. This could greatly improve the autonomy of the elderly, the disabled, and other groups who are not capable of walking long distances.

Motorised trolleys

For use in warehouses, large trolleys are a popular way of transporting goods internally. Moving these trolleys around can be a very demanding task. Using the kind of assistance discussed here could make this task much easier to perform. It would also be beneficial to safety, since the operators will have more control over the trolley. However, it would still be cheaper, more versatile, and easier to operate than a fully motorised solution such as a forklift.

These warehouse trolleys will most likely carry a much heavier load than the suitcases. As such, the frame needs to be stronger, and the drivetrain should be much more powerful. We can expect trolley to apply much more force compared to the user than in the suitcase, so the control software may need to be adapted to work properly when the trolley is expected to apply almost all of the required force.

Another big difference between the use in suitcases and in warehouse trolleys is that security is not very much of a concern here: the trolleys are only used to transport goods internally and are not at risk of being stolen. Therefore, the unlocking system we described would not be necessary here. Furthermore, there could be many of these trolleys and they may be used by many different employees throughout the course of a day. These employees probably won't want to install an app on their phone and pair it with the trolley every time. As such, we think that the Bluetooth connection and smartphone app should not be used in this context. It would be preferable to link all trolleys to a centralised system where a supervisor can observe their position, battery level, etc. This will also require a different interface: not only should it work on PCs rather than phones, it should also be able to display info on multiple trolleys at the same time.

References

- ↑ https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/nieuws/2018/05/ruim-76-miljoen-passagiers-via-nederlandse-luchthavens

- ↑ Alves-Oliveira, P., & Paiva, A. (2016, October). A study on trust in a robotic suitcase. In Social Robotics: 8th International Conference, ICSR 2016, Kansas City, MO, USA, November 1-3, 2016 Proceedings (Vol. 9979, p. 179). Springer., url: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308925691_A_Study_on_Trust_in_a_Robotic_Suitcase

- ↑ Muetze, A., Tan, Y.C., (2007) "Electric Bicycles - A performance evaluation", IEEE Industry Applications Magazine, 12-21, url: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/3408144_Electric_bicycles_-_A_performance_evaluation

- ↑ Kenton, M. (2018, January 11) "Smart luggage" bans - what they mean for airline travelers, url: https://www.travelersunited.org/getting-there/smart-luggage-bans/

- ↑ Udo, W. D. H. (2014). E.U. Patent No. EP 2 590 041 A3, url: http://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/pdfs/d5004bb57f498e9fed5c/EP2590041A3.pdf

- ↑ Kuroda, M. (2009). U.S. Patent No. US 7598706 B2. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office., url: http://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/pdfs/US20100072848.pdf

- ↑ Krinkin, K., Stotskaya, E., & Stotskiy, Y. (2015). Design and implementation Raspberry Pi-based omni-wheel mobile robot. 2015 Artificial Intelligence and Natural Language and Information Extraction, Social Media and Web Search FRUCT Conference (AINL-ISMW FRUCT). doi:10.1109/ainl-ismw-fruct.2015.7382967, url: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/7382967/

- ↑ Ghaderi, A., Sanada, A., Nassiraei, A. A., Ishii, K., & Godler, I. (2008). Power and propulsion systems design for an autonomous omni-directional mobile robot. 2008 Twenty-Third Annual IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition., url: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/4522732/

- ↑ Krishnamohan, T., Mahendran, A., Paramananthasivam, V., Selvakumar, A. (2016). Human following Trolley-Auto Walker, SLIIT conference 2016, url: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318851444_Human_following_Trolley-Auto_Walker

- ↑ Sezer, V., & Gokasan, M. (2012). A novel obstacle avoidance algorithm:“Follow the Gap Method”. Robotics and Autonomous Systems, 60(9), 1123-1134, url: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921889012000838

- ↑ Liu, M. Y., Tuzel, O., massoud Farahmand, A., & Hara, K. (2018). U.S. Patent Application No. 15/218,182.

- ↑ Ju, P., & Zhang, H. (2018). Achievable delay margin using LTI control for plants with unstable complex poles. Science China Information Sciences, 61(9), 092203, url: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11432-017-9185-6

- ↑ Ren, S., He, K., Girshick, R., Zhang, X., & Sun, J. (2017). Object detection networks on convolutional feature maps. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence, 39(7), 1476-1481., url: https://www.computer.org/csdl/trans/tp/preprint/07546875.pdf

- ↑ Cobb, H. S. (1997). GPS pseudolites: Theory, design, and applications (pp. 87-101). Stanford, CA, USA: Stanford University, url: https://web.stanford.edu/group/scpnt/gpslab/pubs/theses/StewartCobbThesis97.pdf

- ↑ Edge, L., & Jobs, G. (2001). Centimeter-accuracy indoor navigation using GPS-like pseudolites., url: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/68ca/cbf271518bbf6f6d177b978f962c9acae0c2.pdf

- ↑ Gu, Y., & Ren, F. (2015). Energy-efficient indoor localization of smart hand-held devices using Bluetooth. IEEE Access, 3, 1450-1461., url: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?arnumber=7118131

- ↑ Palumbo, F., Barsocchi, P., Chessa, S., & Augusto, J. C. (2015, August). A stigmergic approach to indoor localization using bluetooth low energy beacons. In Advanced Video and Signal Based Surveillance (AVSS), 2015 12th IEEE International Conference on (pp. 1-6). IEEE., url: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?arnumber=7301734

- ↑ Nandakumar, R., Chintalapudi, K. K., & Padmanabhan, V. N. (2012, August). Centaur: locating devices in an office environment. In Proceedings of the 18th annual international conference on Mobile computing and networking (pp. 281-292). ACM., url: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/com272-chintalapudi.pdf

- ↑ Flacco, F., Kröger, T., De Luca, A., & Khatib, O. (2012, May). A depth space approach to human-robot collision avoidance. In Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 2012 IEEE International Conference on (pp. 338-345). IEEE., url: https://cs.stanford.edu/groups/manips/publications/pdfs/Flacco_2012_ICRA.pdf