PRE2018 3 Group9: Difference between revisions

| Line 653: | Line 653: | ||

From Newton's second law, the sum of forces acting on the projectile attached to the corners of the net are | From Newton's second law, the sum of forces acting on the projectile attached to the corners of the net are | ||

<math>F = | <math>F = F_press = m a</math> | ||

<math display="block"> \sum F = F_{pres} = ma, </math> | <math display="block"> \sum F = F_{pres} = ma, </math> | ||

Revision as of 09:44, 11 March 2019

Preface

Group Members

| Name | Study | Student ID |

|---|---|---|

| Claudiu Ion | Software Science | 1035445 |

| Endi Selmanaj | Electrical Engineering | 1283642 |

| Martijn Verhoeven | Electrical Engineering | 1233597 |

| Leo van der Zalm | Mechanical Engineering | 1232931 |

Initial Concepts

After discussing various topics we came up with this final list of projects that seemed interesting to us.

- Drone interception

- A tunnel digging robot

- A fire fighting drone for finding people

- Delivery uav - (blood in Africa, parcels, medicine, etc.)

- Voice control robot - (general technique that has many applications)

- A spider robot that can be used to get to hard to reach places

Chosen Project: Drone Interception

Introduction

According to the most recent industry forecast studies, the unmanned aerial systems (UAS) market is expected to reach 4.7 million units by 2020.[1] Nevertheless, regulations and technical challenges need to be addressed before such unmanned aircraft become as common and accepted by the public as their manned counterpart. The impact of an air collision between an UAS and a manned aircraft is a concern to both the public and government officials at all levels. All around the world, the primary goal of enforcing rules for UAS operations into the national airspace is to assure an appropriate level of safety. Therefore, research is needed to determine airborne hazard impact thresholds for collisions between unmanned and manned aircraft or even collisions with people on the ground as this study already shows.[2].

With the recent developments of small and cheap electronics unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) are becoming more affordable for the public and we are seeing an increase in the number of drones that are flying in the sky. This has started to pose a number of potential risks which may jeopardize not only our daily lives but also the security of various high values assets such as airports, stadiums or similar protected airspaces. The latest incident involving a drone which invaded the airspace of an airport took place in December 2018 when Gatwick airport had to be closed and hundreds of flights were cancelled following reports of drone sightings close to the runway. The incident caused major disruption and affected about 140000 passengers and over 1000 flights. This was the biggest disruption since ash from an Icelandic volcano shut down all traffic across Europe in 2010.[3]

Tests performed at the University of Dayton Research Institute show the even a small drone can cause major damage to an airliner’s wing if they meet at more than 300 kilometers per hour.[4]

This project will mostly focus on the importance of interceptor drones for an airport’s security system and the impact of rogue drones on such a system. However, a discussion on drone terrorism, privacy violation and drone spying will also be given and the impacts that these drones can have on users, society and entreprises will be analyzed. As this topic has become widely debated worldwide over the past years, we shall provide an overview of current regulations concerning drones and the restrictions that apply when flying them in certain airspaces. With the research that is going to be carried out for this project, together with all the various deliverables that will be produced, we hope to shine some light on the importance of having systems such as interceptor drones in place for protecting the airspace of the future.

Problem Statement

The problem statement is: How can autonomous unmanned aerial systems be used to quickly intercept and stop unmanned aerial vehicles in airborne situations without endangering people or other goods.

A UAV is defined as an unmanned aerial vehicle and differs from an unmanned aerial system (UAS) in one major way: a UAV is just referring to the aircraft itself, not the ground control and communications units.[5]

Objectives

- Determine the best UAS that can intercept another UAV in airborne situations

- Improve the chosen concept

- Create a design for the improved concept, including software and hardware

- Build a prototype

- Make an evaluation based on the prototype

Project Organisation

Approach

The aim of our project is to deliver a prototype and model on how an interceptive drone can be implemented. The approach to reach this goal contains multiple steps.

Firstly, we will be going to research papers which describe the state of art of such drones and its respective components. This allows our group to get a grasp of the current technology of such a system and introduce us to the new developments in this field. This also helps to create a foundation for the project, which we can develop into. The state of art also gives valuable insight into possible solutions we can think and whether their implementation is feasible given the knowledge we possess and the limited time. The SotA research will be achieved by studying the literature, recent reports from research institutes and the media and analyzing patents which are strongly connected to our project.

Furthermore, we will continue to analyze the problem from a USE – user, society, enterprise – perspective. An important source of this analysis is the state of art research, where the impact of these drone systems in different stakeholders discussed. The USE aspects will be of utmost importance for our project as every engineer should strive to develop new technologies for helping not only the users but also the society as a whole and also avoid the possible consequence of the system they develop. This analysis will finally lead to a list of requirements for our solutions. Moreover, we will discuss the impact of these solutions on the categories listed prior.

Finally, we hope to develop a prototype for an interceptor drone. We do not plan on making a physical prototype as the time of the project is not feasible for this task. We plan on creating a 3D model of the drone and simulating it, showcasing its functionality in real life. To complement this, we also plan on building an Android application, which serves as a dashboard for the drone tracking different parameters about the drones such as position and overall status. To realize this a list of hardware components will be researched, which would be feasible with our project and create a cost-effective product. Concerning the software, a UML diagram will be created first, to represent the system which will be implemented later on. Together with the wiki page, these will be our final deliverables for the project.

Below we summarize the main steps in our approach of the project.

- Doing research on our chosen project using SotA literature analysis

- Analyzing the USE aspects and determining the requirements of our system

- Consider multiple design strategies

- Choose the Hardware and create the UML diagram

- Work on the prototype (3D model and mobile application)

- Evaluate the prototype

Milestones

Within this project there are three major milestones:

- After week 2, the best UAS is chosen, options for improvements of this system are made and also there is a clear vision on the user. This means that it is known who the users are and what their requirements are.

- After week 5, the software and hardware are designed for the improved system. Also a prototype has been made.

- After week 8, the wiki page is finished and updated with the results that were found from testing the prototype. Also future developments are looked into and added to the wiki page.

Deliverables

- This wiki page, which contains all of our research and findings

- A presentation, which is a summary of what was done and what our most important results are

- A prototype

Planning

The plan for the project is given in the form of a table in which every team member has a specific task for each week. There are also group tasks which every team member should work on. The plan also includes a number of milestones and deliverables for the project.

| Name | Week #1 | Week #2 | Week #3 | Week #4 | Week #5 | Week #6 | Week #7 | Week #8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research | Requirements and USE Analysis | Hardware Design | Software Design | Prototype / Concept | Proof Reading | Future Developments | Conclusions | |

| Claudiu Ion | Make a draft planning | Add requirements for drone on wiki | Regulations and Present Situation | Write pseudocode for interceptor drone | Mobile app development | Proof read the wiki page and correct mistakes | Review wiki page | Make a final presentation |

| Summarize project ideas | Improve introduction | Wireframing the Dashboard App | Build UML diagram for software architecture | Review wiki page | ||||

| Write wiki introduction | Check approach | Start design for dashboard mobile app | Mobile app development | |||||

| Find 5 research papers | ||||||||

| Endi Selmanaj | Research 6 or more papers | Elaborate on the SotA | Research the hardware components | Work on the drone model | Work on 3D drone model / prototype | Reviewing the Wiki and fixing spelling errors | Finalise the Wiki Page | Work on final presantation |

| Write about the USE aspects | Review the whole Wiki page | Purchase or request the needed hardware | Work on the code needed for the electronics | Finish the simulation | Work on the layout of the Wiki | Check on the relaisation of all objectives | ||

| Improve approach | Draw the schematics of electronics used | Start with the simulation | Expand on the material on the Wiki more | |||||

| Check introduction and requirements | ||||||||

| Martijn Verhoeven | Find 6 or more research papers | Update SotA | Research hardware options | Start on 3D model of drone | Work on 3D model | Review wiki page | Finalise wiki page | |

| Fill in draft planning | Check USE | Start thinking about electronics layout | Make a bill of costs and list of parts | Deliver 3D model of drone | ||||

| Write about objectives | ||||||||

| Leo van der Zalm | Find 6 or more research papers | Update milestones and deliverables | Start on 3D model of drone | Work on 3D model | Review wiki page | Continue tasks from week 7 | Finish all lose ends | |

| Search information about subject | Check SotA | Research hardware components | Make a bill of costs and list of parts | Put in new devellopmets from week 3, 4 and 5 | Write future developmetns | Write conclusion/results part | ||

| Write problem statements | USE analysis including references | Start looking at the final presentation | ||||||

| Write objectives | ||||||||

| Group Work | Introduction | Expand on the requirements | Research hardware components | Interface design for the mobile app | Start working on the visualisation | |||

| Brainstorming ideas | Expand on the state of the art | Research systems for stopping drones | Start working on drone prototype | |||||

| Find papers (5 per member) | Society and enterprise needs | Start working on 3d drone model | ||||||

| User needs and user impacts | Work on UML activity diagram | Start working on the simulation | ||||||

| Define the USE aspects | Improve week 1 topics | |||||||

| Milestones | Decide on research topic | Add requirements to wiki page | USE analysis finished | Provide a bill of costs and list of parts | Mobile app prototype finished | Visualisation finished | ||

| Add research papers to wiki | Add state of the art to wiki page | UML activity diagram finished | 3D drone model finished | |||||

| Write introduction for wiki | Research into building a drone | |||||||

| Finish planning | Research into the costs involved | |||||||

| Deliverables | Mobile app prototype | Final presentation | ||||||

| 3D drone model | Wiki page |

USE

In this section we will focus more on analysing the different aspects involving users, society and enterprises in the context of interceptor drones. We will start by identifying key stakeholders for each of the categories and proceed by giving a more in depth analysis. After identifying all these stakeholders, we will continue by stating what our project will mainly focus on in terms of stakeholders. Since the topic of interceptor drones is quite vast depending from which angle we choose to tackle the problem, focusing on a specific group of stakeholders will help us produce a better prototype and conduct better research for that group. Moreover, each of these stakeholders experiences different concerns, which are going to be elaborated separately.

Users

When analysing the main users for an interceptor drone, we quickly see that airports are the most interested in having such a technology. This comes as no surprise when we look at the number of incidents involving rogue drones around airports in the last couple of years. Due to the fact that the airspace within and around airports is heavily restricted and regulated, it is clear that unauthorized flying drones are a real danger not only to the operation of airports and airlines, but also to the safety and comfort of passengers. As was the case with previous incidents, intruder drones which are violating airport airspaces lead to airport shutdowns which result in big delay and huge losses.

Another key group of users is represented by governmental agencies and civil infrastructure operators that want to protect certain high value assets such as embassies. As one can imagine, having intruder drones flying above such a place could lead to serious problems such as diplomacy fights or even impact the relations between the two countries involved. Therefore, one could argue that such a drone could indeed be used with malicious intent to directly cause such tense relations. Another good example worth mentioning is the incident involving the match between Serbia and Albania in 2014 when a drone invaded the pitch carrying an Albanian nationalist banner which lead to a pitch invasion by the Serbian fans and full riot. Needless to say, this incident led to retaliations from both Serbians and Albanians which resulted in significant material damage and damaged even more the fragile relations between the two countries [6].

We can also imagine such an interceptor drone being used by the military or other government branches for fending off terrorist attacks. Being able to deploy such a countermeasure (on a battlefield) would improve improve not only the safety of people but would also help in deterring terrorists from carrying our such acts of violence in the first place.

Lastly, a smaller group of users, but still worth taking into account could be represented by individuals who are prone to get targeted by drones, therefore having their privacy violated by such systems. This could be the case with celebrities or other VIPs who are targeted by the media to get more information about their private lives. To summarize, from a user perspective we think that the research which will go into this project can benefit airport security systems the most. One could say that we are taking an utilitarianism approach to solving this problem, as implementing a security systems for airports would produce the greatest good for the greatest number of people.

Society

When thinking how society could benefit from the existence of a system that detects and stops intruder drones, the best example to consider is again the airport scenario. It is already clear that whenever an unauthorized drone enters the restricted airspace of an airport this causes major concern for the safety of the passengers. Moreover, it causes huge delays and creates big problems for the airport’s operations and airlines which will be losing a lot of money. Apart from this, rogue drones around airports cause logistical nightmares for airports and airlines alike since this will not only create bottlenecks in the passengers flow through the airport but airlines might need to divert passengers on other routes and planes. The cargo planes will also suffer delays and this could lead to bigger problems down the supply chain such as medicine not reaching patients in time. All these problems are a great concern for the society as a whole.

Another big issue for society which interceptor drones hope to solve would be the ability to safely stop a rogue drone from attacking large crowds of people at various events for example. For providing the necessary protection in these situations, it is crucial that the interceptor drone acts very quickly and stops the intruder in a safe and controlled manner as fast as possible without putting the lives of other people in danger. Again, when we think in the context of providing the greatest good for the greatest number of people, the airport security example stands out, therefore this is where the main focus of the research of this paper will be aimed at.

Enterprise

When analysing the impact interceptor drones will have on the enterprise in the context of airport security we identify two main players: the airport security and airlines operating from that airport. Moreover, the airlines can be further divided into two categories: those which transport passengers and those that transports cargo (and we can also have airlines that do both).

From the airport’s perspective, a drone sighting near the airport would require a complete shutdown of all operations for at least 30 minutes, as stated by current regulations [7]. As long as the airport is closed, it will lose money and cause huge operational problems if we think at the number of people left stranded all over the airport waiting for the next flight out. Furthermore, when the airport will open again, there will be even more problems caused by congestion since all planes would want to leave at the same time which is obviously not possible. This can actually lead to incidents on the tarmac involving planes, due to improper handling or lack of space in an airport which is potentially already overfilled with planes.

From the airline’s perspective, whether we are talking about passengers transport or cargo, drones violating an airport’s airspace directly translates in huge losses, big delays and unhappy passengers. Not only will the airline need to compensate passengers in case the flight is canceled, but they would also need to support accommodation expenses in some cases. For cargo companies, a delay in delivering packages can literally mean life or dead if we talk about medicine that needs to get to patients. Moreover, disruptions in the transport of goods can greatly impact the supply chain of numerous other businesses and enterprises, thus these types of events (rogue drones near airports) could have even bigger ramifications.

Finally, after analyzing the USE implications of intruder drones in the context of airport security, we will now focus on researching different types of systems than can be deployed in order to not only detect but also stop and catch such intruders as quickly as possible. This will therefore help mitigate both the risks and various negative implications that such events have on the USE stakeholders that were mentioned before.

Requirements

In order to better understand the needs and design for an interceptor drone, a list of requirements is necessary. There are clearly different ways in which a rogue UAV can be detected, intercepted, tracked and stopped. However, the requirements for the interceptor drone need to be analyzed carefully as any design for such a system must ensure the safety of bystandars and minimize all possible risks involved in taking down the rogue UAV. Equally important are the constraints for the interceptor drone and finally the preferences we have for the system. For prioritizing the specific requirements for the project, the MoSCoW model was used. Each requirement has a specific level of priority which stands for must have (M), should have (S), could have (C), would have (W). We will now give the RPC table for the autonomous interceptor drone and later provide some more details about each specific requirement.

| ID | Requirement | Preference | Constraint | Category | Priority |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | Detect rogue drone | LIDAR system for detecting intruders | Does NOT require human action | Software | M |

| R2 | Autonomous flight | Fully autonomous drone | Does NOT require human action | Software & Control | M |

| R3 | Object recognition | Accuracy of 100% | Uses AI bounding box algorithm | Software | M |

| R4 | Detect rogue drone's flying direction | Accuracy of 100% | Software & Hardware | S | |

| R5 | Detect rogue drone's velocity | Accuracy of 100% | Software & Hardware | S | |

| R6 | Track target | Tracking targer for at least 10 minutes | Allows for operator to correct drone | Software & Hardware | M |

| R7 | Velocity of 40 km/h | Drone is as fast as possible | Hardware | S | |

| R8 | Flight time of 10 minutes | Flight time is maximized | Hardware | M | |

| R9 | FPV live feed (with 60 FPS) | Drone records and transmits flight video | Records all flight video footage | Hardware | W |

| R10 | Camera of 1080p | Flight video is as clear as possible | Hardware | C | |

| R11 | Stop rogue drone | Is always successful | Can NOT be violet or endanger others | Hardware | M |

| R12 | Stable connection to operation base | Drone is always connected to base | If connection is lost drone buffers data | Software | S |

| R13 | Sensor monitoring | Drone sends sensor data to base and app | All sensor information is sent to base | Software | S |

| R14 | Return to home functionality | Drone autonomously returns home | Software | C | |

| R15 | Auto take off | Control | M | ||

| R16 | Auto landing | Control | M | ||

| R17 | Auto leveling (in flight) | Drone is able to fly in heavy weather | Does NOT require human action | Control | M |

| R18 | Minimal weight | Drone uses carbon fiber materials | Hardware | S | |

| R19 | Cargo capacity of 4 kg | Drone is able to carry two catching devices | Hardware | S | |

| R20 | Portability | Drone is portable and easy to transport | Does NOT hinder drone's robustness | Hardware | C |

| R21 | Fast deployment | Drone can be deployed in under 5 minutes | Does NOT hinder drone's robustness | Hardware | C |

| R22 | Minimal costs | Drone cost is less than 800 euros | Costs | S |

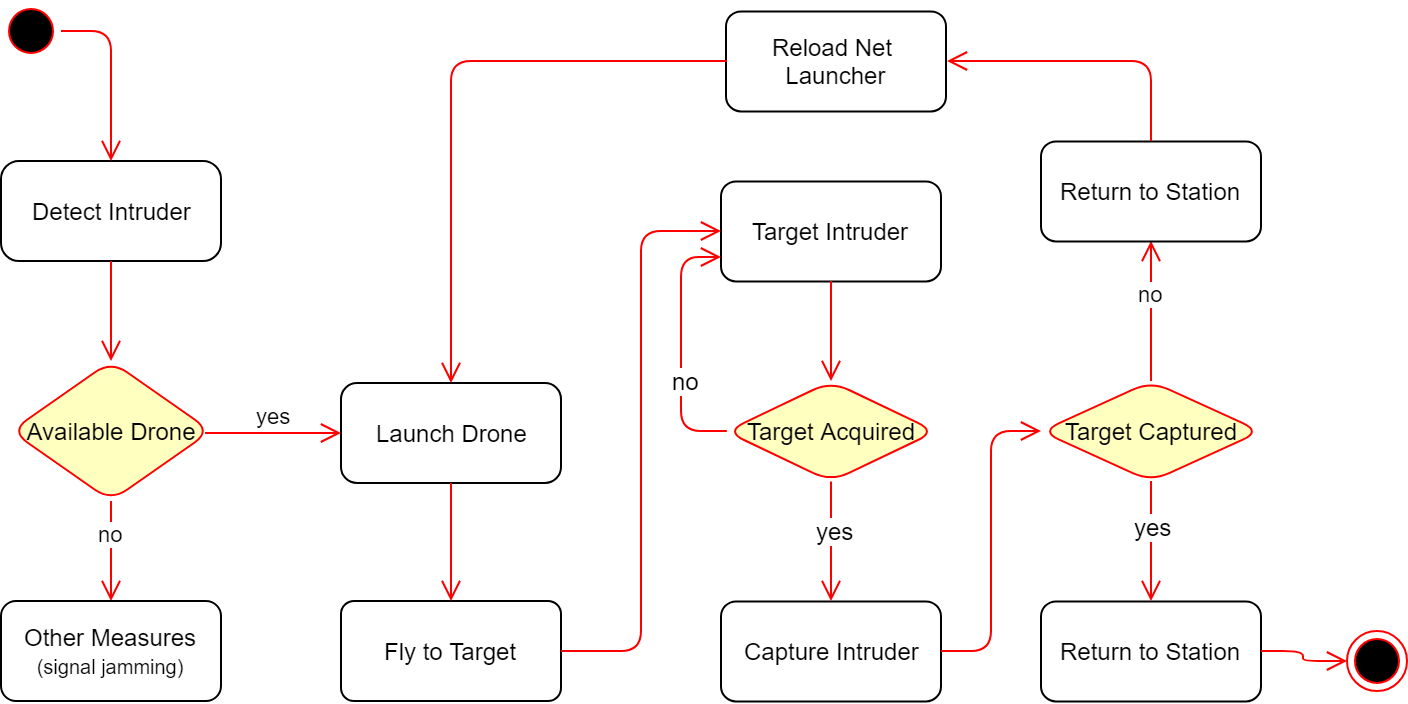

UML Activity Diagram

Activity diagrams, along with use case and state machine diagrams describe what must happen in the system that is being modeled and therefore they are also called behavior diagrams. Since stakeholders have many issues to consider and manage, it is important to communicate what the overall system should do with clarity and map out process flows in a way that is easy to understand. For this, we will give an activity diagram of our system, including the overview of how the interceptor drone will work. By doing this, we hope to demonstrate the logic of our system and also model some of the software architecture elements such as methods, functions and the operation of the drone.

Regulations

The world’s airspace is divided into multiple segments each of which is assigned to a specific class. The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) specifies this classification to which most nations adhere to. In the US however, there are also special rules and other regulations that apply to the airspace for reasons of security or safety.

The current airspace classification scheme is defined in terms of flight rules: IFR (instrument flight rules), VFR (visual flight rules) or SVFR (special visual flight rules) and in terms of interactions between ATC (air traffic control). Generally, different airspaces allocate the responsibility for avoiding other aircraft to either the pilot or the ATC.

ICAO adopted classifications

Note: These are the ICAO definitions.

- Class A: All operations must be conducted under IFR. All aircraft are subject to ATC clearance. All flights are separated from each other by ATC.

- Class B: Operations may be conducted under IFR, SVFR, or VFR. All aircraft are subject to ATC clearance. All flights are separated from each other by ATC.

- Class C: Operations may be conducted under IFR, SVFR, or VFR. All aircraft are subject to ATC clearance (country-specific variations notwithstanding). Aircraft operating under IFR and SVFR are separated from each other and from flights operating under VFR, but VFR flights are not separated from each other. Flights operating under VFR are given traffic information in respect of other VFR flights.

- Class D: Operations may be conducted under IFR, SVFR, or VFR. All flights are subject to ATC clearance (country-specific variations notwithstanding). Aircraft operating under IFR and SVFR are separated from each other, and are given traffic information in respect of VFR flights. Flights operating under VFR are given traffic information in respect of all other flights.

- Class E: Operations may be conducted under IFR, SVFR, or VFR. Aircraft operating under IFR and SVFR are separated from each other, and are subject to ATC clearance. Flights under VFR are not subject to ATC clearance. As far as is practical, traffic information is given to all flights in respect of VFR flights.

- Class F: Operations may be conducted under IFR or VFR. ATC separation will be provided, so far as practical, to aircraft operating under IFR. Traffic Information may be given as far as is practical in respect of other flights.

- Class G: Operations may be conducted under IFR or VFR. ATC has no authority but VFR minimums are to be known by pilots. Traffic Information may be given as far as is practical in respect of other flights.

Special Airspace: these may limit pilot operation in certain areas. These consist of Prohibited areas, Restricted areas, Warning Areas, MOAs (military operation areas), Alert areas and Controlled firing areas (CFAs), all of which can be found on the flight charts.

Note: Classes A–E are referred to as controlled airspace. Classes F and G are uncontrolled airspace.

Currently, each country is responsible for enforcing a set of restrictions and regulations for flying drones as there are no EU laws on this matter. In most countries, there are two categories for drone pilots: recreational drone pilots (hobbyists) and commercial drone pilots (professionals). Depending on the use of such drones, there are certain regulation that apply and even permits that a pilot needs to obtain before flying.

For example, in The Netherlands, recreational drone pilots are allowed to fly at a maximum altitude of 120m (only in Class G airspace) and they need special permission for flying at a higher altitude. Moreover, the drone need to remain in sight at all times and the maximum takeoff weight is 25 kg. For recreational pilots, a licence is not required, however flying at night needs special approval. For commercial drone pilots, one or more permits are required depending on the situations. The RPAS (remotely piloted aircraft system) certificate is the most common licence and will allow for pilots to fly drones for commercial use. The maximum height, distance and takeoff limits are increased compared to the recreational use of such drones, however night time flying still requires special approval and drones still need to be flown in Class G airspace.

Apart from these rules, there are certain drone ban zones which are strictly forbidden for flying and these are: state institutions, federal or regional authority constructions, airport control zones, industrial plants, railway tracks, vessels, crowds of people, populated areas, hospitals, operation sites of police, military or search and rescue forces and finally the Dutch Caribbean Islands of Bonaire St.Eustatius and Saba. Failing to abide by the rules may result in a warning or a fine. The drone may also be confiscated. The amount of the fine or the punishment depends on the type of violation. For example, the judicial authorities will consider whether the drone was being used professionally or for hobby purposes, and whether people have been endangered.

As it is usually the case with new emerging technologies, the rules and regulations fail to keep up with the technological advancements. However, recent developments in the European Parliament hope to create a unified set of laws concerning the use of drones for all European countries. A recent study suggests that the rapid developing drone sector will generate up to 150000 jobs by 2050 and in the future this industry could account for 10% of the EU’s aviation market which amounts to 15 billion euros per year. Therefore, there is definitely need to change the current regulation which in some cases complicates cross border trade in this fast growing sector. As shown with the previous example, unmanned aircraft weighing less than 25 kg (drones) are regulated at a nationwide level which leads to inconsistent standards across different countries. Following a four months consultation period, the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) published a proposal for a new regulation for unmanned aerial systems operation in open (recreational) and specific (professional) categories. On the 28th February 2019, the EASA Committee has given its positive vote to the European Commission proposal for implementing the regulations which are expected to be adopted at the latest on 15 March 2019. Although these are still small steps, the EASA is working on enabling safe operations of unmanned aerial systems (UAS) across Europe’s airspaces and the integration of these new airspace users into an already busy ecosystem.

The Interceptor Drone

Catching a Drone

The next step is to look at the device which we use to intercept the drone. This could be done with another drone, which we suggested above. But there is also another option. This is by shooting the drone down with a specialized gun, like the ‘Skywall 100’ from OpenWorks Engineering.[8] This British company invented a net gun which is specialized in shooting down drones. It is manual and has a short reload time. This way, taking down the drone is easy and fast, but it has two big problems. The first one is that the drone falls to the ground after it is shot down. This way it could fall onto people or even worse, conflict enormous damage when the drone is armed with explosives. Therefore the ‘Skywall 100’ cannot be used in every situation. Another problem is that this gun is manual, and a human life can be at risk in situations when an armed drone must be taken down.

There remain two alternatives by which another drone is used to catch the violating drone. No human lives will be at risks and the violating drone can be delivered at a desired place. The first option is by using an interceptor drone, which deploys a net in which the drone is caught. This is an existing idea. A French company named MALOU-tech, has built the Interceptor MP200.[9] But this way of catching a drone has some side-effects. On the one hand, this interceptor drone can catch a violating drone and deliver it at a desired place. But on the other hand, the relatively big interceptor drone must be as fast and agile as the smaller drone, which is hard to achieve. Also, the net is quite rigid and when there is a collision between the net and the violating drone, the interceptor drone must be stable and able to find balance, otherwise it will fall to the ground. Another problem that occurs is that the violating drone is caught in the net, but not sealed in it. It can easily fall out of the net or not even be able to be caught in the net. Drones with a frame that protect the rotor blades well are not able to get caught because the rotor blades cannot get stuck in the net.

Drones like the Interceptor MP 200 are good solutions to violating drones which need to be taken down, but we think that there is a better option. When we implement a net launcher onto the interceptor drone and remove the big net, this will result in better performance because of the lower weight. But when the shot is aimed correctly, the violating drone is completely stuck in the net and can’t get out, even if it has blade guards. This is important when the drone is equipped with explosives. In this case we must be sure that the armed drone is neutralized completely, meaning that we know for sure that it cannot escape or crash in an unforeseen location. This is an existing idea, and Delft Dynamics built such a drone.[10]. This drone however is, in contrary to our proposed design, not fully autonomous.

Building the Interceptor Drone

Building a drone, like most other high-tech current day systems, consists of hardware as well as software design. In this part we like to focus on the software and give a general overview of the hardware. This is because our interests are more at the software part, where a lot more innovative leaps can still be made. In the hardware part we will provide an overview of drone design considerations and a rough estimation of what such a drone would cost. In the software part we are going to look at the software that makes this drone autonomous. First, we look at how to detect the intruder, how to target it and how to assure that it has been captured. Also, a dashboard app is shown, which displays the real time system info and provides critical controls.

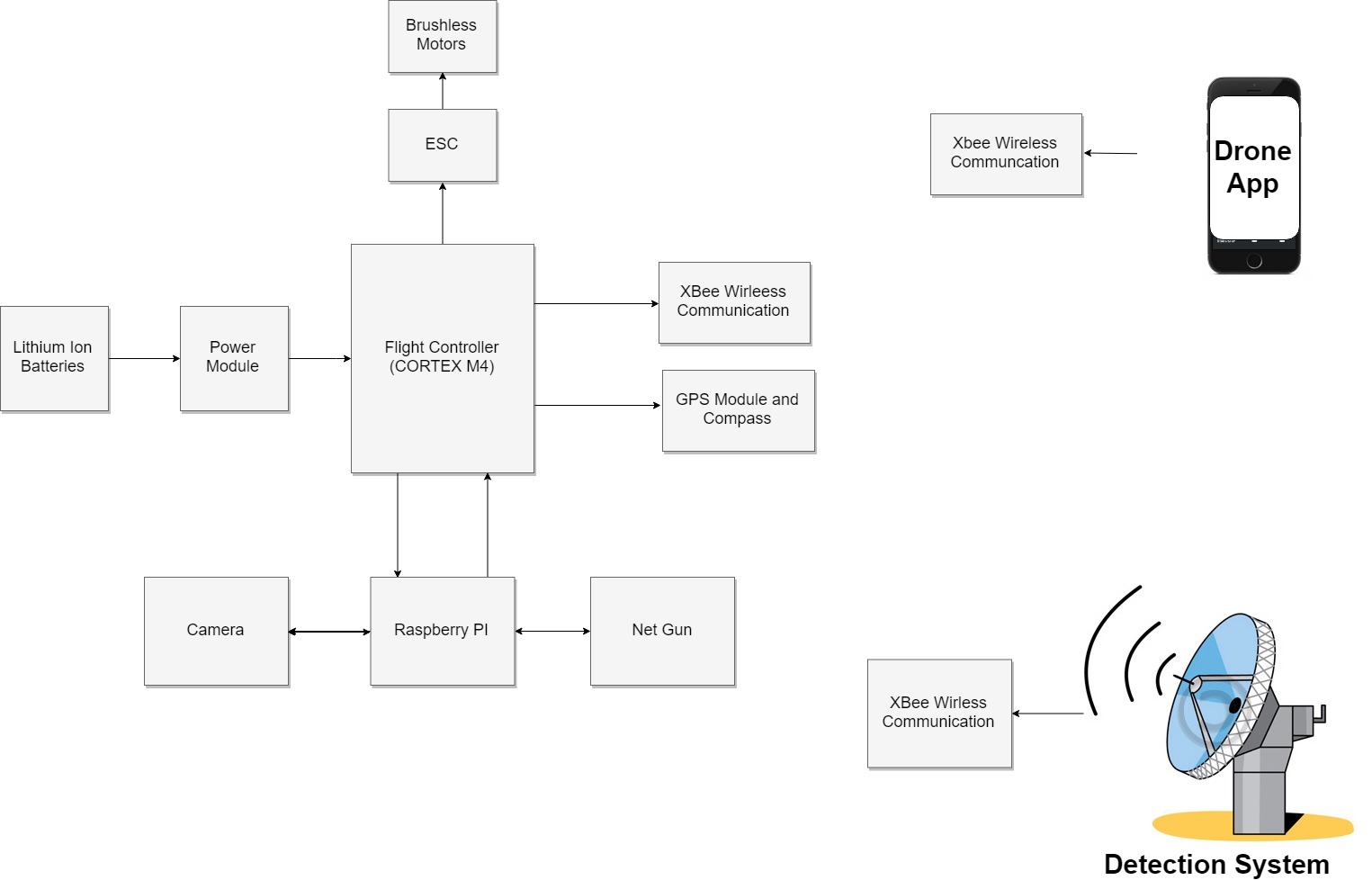

Hardware/Software interface

The main unit of the drone is the flight controller which is made out of an ST Cortex M4 Processor. This unit serves as the brain of the drone. The drone itself is powered by high capacity Lithium-Ion Batteries. The power of the batteries goes through a power module, that makes sure the drone is fed constant power, while measuring the voltage and current going through it, detecting when an anomaly with the power is happening or when the drone needs recharging. The code for autonomous flight is coded into the Cortex M4 chip, which through the Electronic Speed Controllers can control the Brushless DC Motors which spin the propellers to make the drone fly. Each Motor has its own ESC, meaning that each motor is controlled separately.

For the intent of having the drone position in real time, a GPS module is used, which provides a fairly accurate location for outdoor flight. This module communicates with the Cortex M4 to process and update the location of the drone in relation to the location target.

To be able to detect an intruder drone with the help of computer vision, a Raspberry Pi is placed into the drone to offer the extra computation power needed. Raspberry Pi is connected to a camera, with which it can detect the attacking drone. After the target has been locked into position, the net gun is launched towards the attacking drone. The drone communicates with a system located near the area of surveillance. It uses XBee Wireless Communication to do so, with which it receives and transmits data. The drone uses this first for communicating with the app, where all the data of the drone is displayed. The other use of wireless communication is to communicate with the detection system placed around the area. This can consist of a radar-based system or external cameras, connected to the main server, which then communicates the rough location of the intruder drone back.

Hardware

From the requirements a general design of the drone can be created. The main requirements concerning the hardware design of the drone are:

- Velocity of 40km/h

- Flight time of 10 minutes

- FPV live feed

- Stop rogue drone

- Minimal weight

- Cargo capacity of 8kg

- Portability

- Fast deployment

- At minimal cost

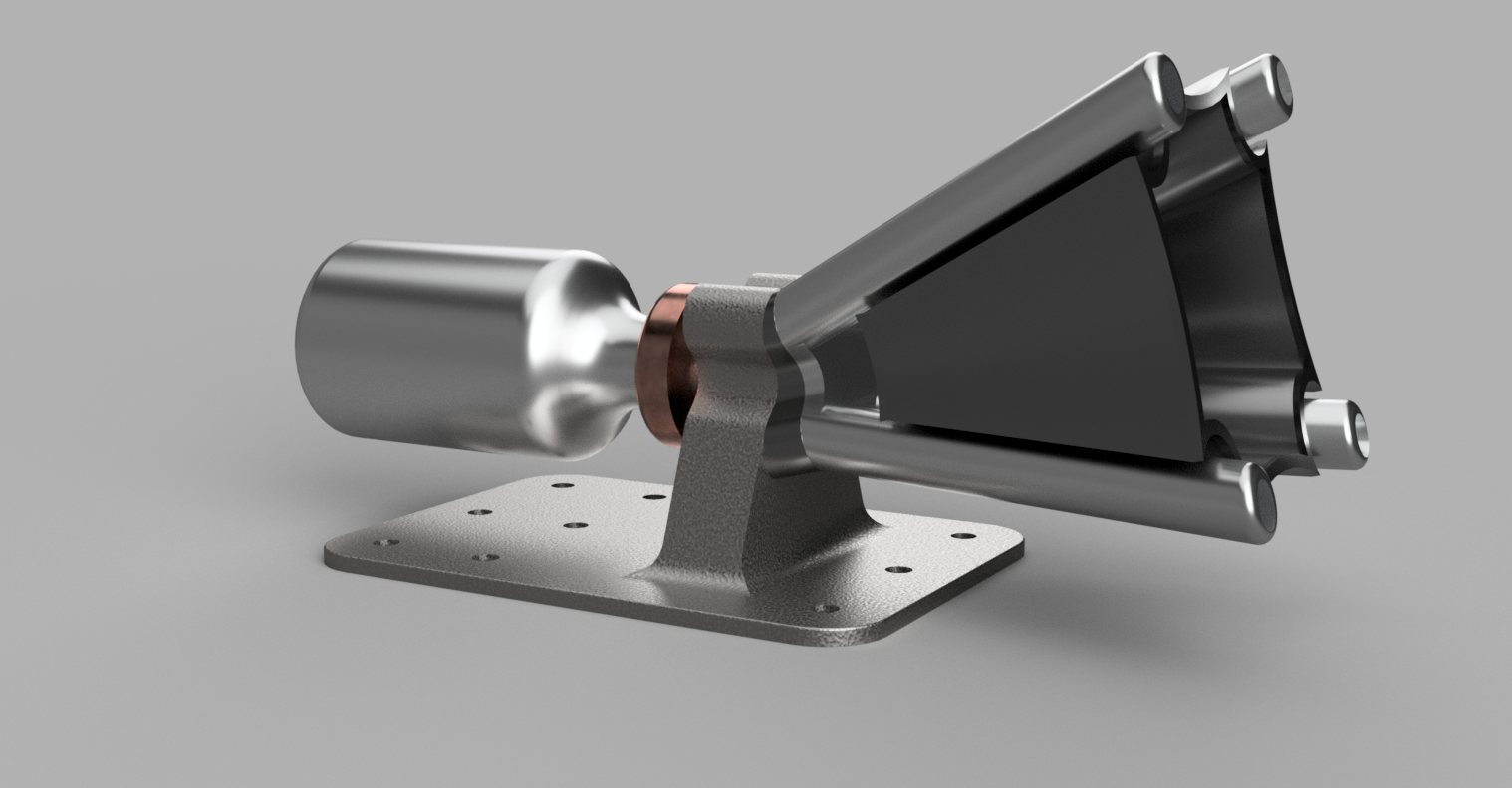

A big span is required, in order to stay stable while carrying high weight (i.e. an intruder with heavy explosives). This is due to the higher leverage of rotors at larger distances. But with the large format the portability and maneuverability decrease. Based on the intended maximum target weight of 8kg, a drone of roughly 80cm has been chosen. The chosen design uses eight rotors instead of the more common four or six (also called an octocopter, [3]) to increase maneuverability and carrying capacity. By doing so, the flight time will decrease and costs will increase. Flight time however is not a big concern as a typical interceptor routine will not take more than ten minutes. For quick recharging, a system with automated battery swapping can be deployed.[11] Another important aspect of this drone will be its ability to track another drone. To do so, it is equipped with two cameras. The fpv-camera is low resolution and low latency and is used for tracking. Because of its low resolution, it can also real time be streamed to the base station. The drone is also equipped with a high resolution camera which captures images at a lower framerate. These images are streamed to the base station and can be used for identification of intruders. Both cameras are mounted on a gimbal to the drone to keep their feeds steady at all times such that targeting and identification gets easier. The drone is equipped with a net gun in order to stop the targeted intruder as described in the section “How to catch a drone”.

To clarify our hardware design, we have made a 3D model of the proposed drone and the net launcher. This model is based on work from Felipe Westin on GrabCad [4] and extended with a net launcher.

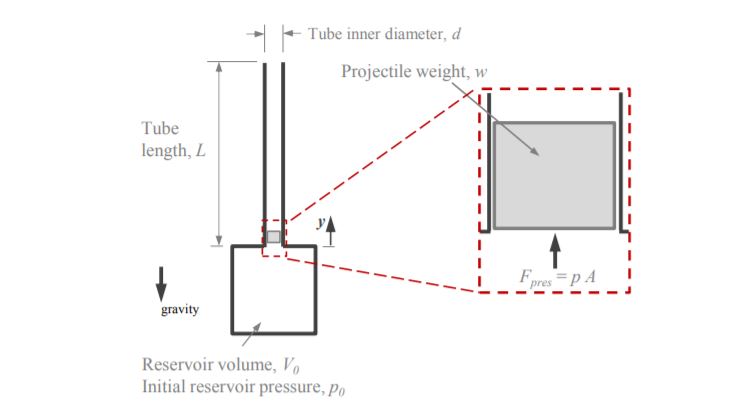

Net Gun mathematical modeling

The net gun of the drone uses a pneumatic launcher to shoot the net. To fully understand its capabilities and how to design it, a model needs to be derived first.

From Newton's second law, the sum of forces acting on the projectile attached to the corners of the net are

[math]\displaystyle{ F = F_press = m a }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ \sum F = F_{pres} = ma, }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \F_{pres}=pA }[/math] with p being the pressure on the projectile and A the crossectional area.

Using these equations, we calculate that

[math]\displaystyle{ pA=mv\frac{\mathrm{d}v }{\mathrm{d} y}. }[/math]

For the pneumatic launcher to function we need a chamber with carbon dioxide, using it to push the projectile. We will assume that no heat is lost through the tubes of the net launcher and that his gas expands adiabatically. The equation describing this process is

[math]\displaystyle{ p_{0}V_{0}^{\gamma }=pV^{\gamma }, }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ p_{0} }[/math] is the inital pressure , [math]\displaystyle{ V_{0} }[/math] is the inital volume of the gas, [math]\displaystyle{ /gamma }[/math] is the ratio of the specific heats at constant pressure and at constant pressure, which is 1.4 for air between 26.6 degrees and 49 degrees and [math]\displaystyle{ V= V_{0} + Ay }[/math] is the volume at any point in time. After adjusting the previous formulas, we get the following

[math]\displaystyle{ \left [ p_{0}\left ( \frac{V_{0}}{V_{0}+Ay} \right ) ^{\gamma }\right ]A=mv\frac{\mathrm{d} v}{\mathrm{d} y}. }[/math]

After integrating from [math]\displaystyle{ y=0 }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ y=L }[/math], where L is the length of the projectile tube, we can find the speed which the projectile lives the muzzle, given by

[math]\displaystyle{ v_{out}=\sqrt{\frac{2p_{0}V_{0}}{m(\gamma -1)}\left [ 1-\left ( \frac{V_{0}}{\frac{\pi }{4}d^2L+V_{0}} \right )^{\gamma } \right ]}. }[/math]

As there is a projectile motion by the net, assuming that friction and tension forces are negligible we get the following equations for the x and y position at any point in time t:

[math]\displaystyle{ y= -y_{0} +V_{out}\sin (\alpha )t + \frac{gt^2}{2}, }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ x= V_{out}\cos (\alpha )t , }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ y_{0} }[/math] is the initial height and [math]\displaystyle{ /alpha }[/math] is the angle that the projectile forms with the x-axis.

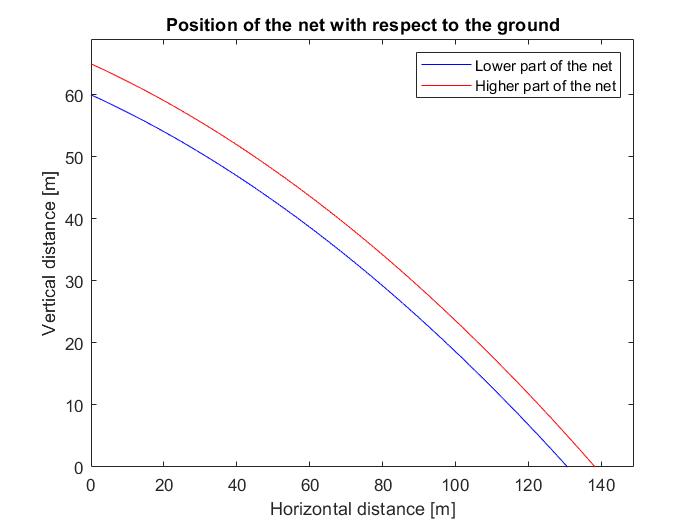

Assuming a speed of 60 [math]\displaystyle{ m/s }[/math], we can plot the position of the net in a certain time point, helping us predict where our drone needs to be in order for it to successfully launch the net to the other drone.

Bill of costs

If we wanted to build the drone, we first start with the frame. In this frame it must be able to implement eight motors. Suitable frames can be bought at a price around 2000 euros. The next step is to implement motors into this frame. Our drone has to able to follow the violating drone, so it has to be fast. Motors with 1280kv are able to reach a velocity of 80 kilometers per hour. This motors cost about 150 euros each. The motors need power which comes from the battery. The price of the battery is a rough estimation. This is because we do not exactly know how much power our drone needs and how much it is going to weigh. Intelligent flight batteries differ in Ampère's. Because this is a price estimation we take a battery which generates 4500mAh and costs about 200 euros. Also two camera's are needed as explained before. FPV-camera's for racing drones cost about 50 euro. High resolution cameras can costs as much as you want. But we need to keep the price reasonable so the camera which we implement gives us 5.2K Ultra HD at 30 frames per second. These two cameras and the net gun need to be attached on a gimbal. A strong and stable enough gimbal costs about 2000 euros. Further costs are electronics such as a flight controller, an ESC, antennas, transmitters and cables.

| Parts | Number | Estimated cost |

|---|---|---|

| Frame and landing gear | 1 | ≈ €2000,- |

| Motor and propellor | 8 | ≈ €1200,- |

| Battery | 1 | ≈ €200,- |

| FPV-camera | 1 | ≈ €50,- |

| High resolution camera | 1 | ≈ €2000,- |

| Gimbal | 1 | ≈ €2000,- |

| Net gun | 1 | ≈ €1000,- |

| Electronics | ≈ €1000,- | |

| Other | ≈ €750,- | |

| Total | ≈ €10200,- |

Software

Automatic target recognition

For the drone to be able to track and target the intruder, it needs to know where the intruder is. To do so, various techniques have been developed over the years all belonging to the area of Automatic Target Recognition (also referred to as A.T.R.). A popular sensor tool is the camera. This is because of its low weight and cost but its high amount of available information. This high amount of information does induce the need for a lot of filtering to get the required information from the camera. Doing so is computationally heavy and therefore our drone carries a Raspberry Pi next to its flight controller to do the heavy image processing. Because our camera is moving with respect to its reference frame (since it is on the flying drone), not all techniques are applicable. These are for example ones that filter out background data by comparing many frames.

An alternative technology is based around the idea of particle filters. Using this particle filter and color-based information, a robust estimation of the target's position, orientation and scale can be made. [12]

The acquired information of the target is than used to control the intervening drone’s position and yaw angle in order to chase the target.

Application

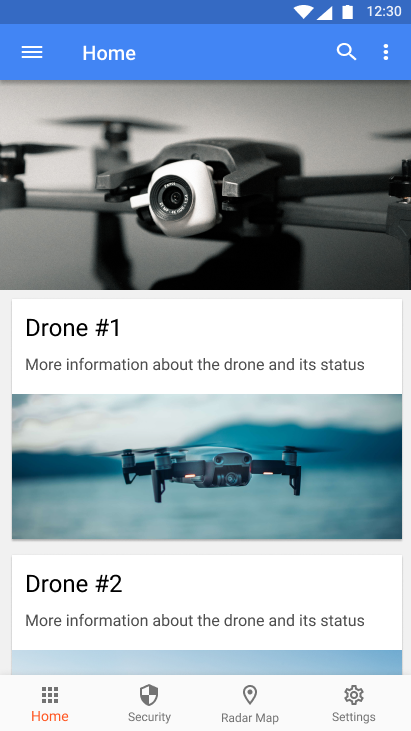

For the interceptor drone system there will be a mobile application developed from which the most important statistics about the interceptor drones can be viewed and also some key commands can be sent to the drone fleet. This application will also communicate with the interceptor drone (or drones if multiple are deployed) in real time, thus making the whole operation of intercepting and catching an intruder drone much faster. Being able to see the stats of the arious interceptor drones in one’s fleet is also very nice for the users and the maintenance personnel who will need to service the drones. A good example that shows how useful the application will be is when a certain drone returns from a mission, the battery levels can immediately be checked using the app and the drone can be charged accordingly.

Note: there will be no commands being sent from the application to the drone. The application's main purpose is to display the various data coming from the drones such that users can better analyze the performance of the drones and maintenance personnel can service the drones quicker.

For building the application, the UI wireframe was first designed. This will make building the final application easier, since the overall layout is already known. The UI wireframe for the application’s main pages is shown below together with some details for each of the application's screens explaining the overall functionality.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

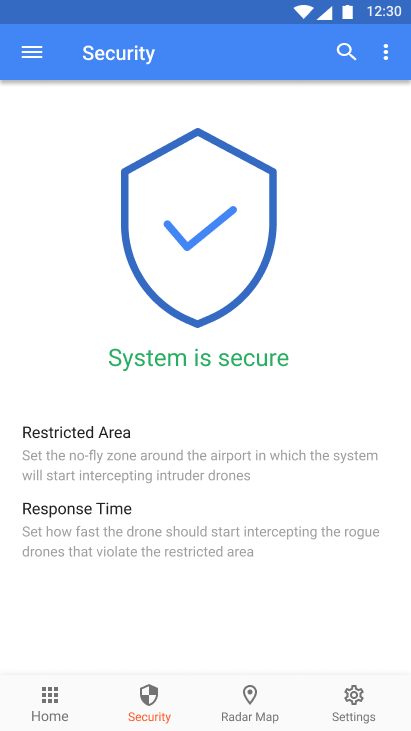

Securing the Application

Since the application will allow for configuration of sensitive information regarding the interceptor drone fleet, users will be required to Login prior to using the app. This ensures that some user can only make new modifications and change settings to the drone fleet that they own or have permissions for changing. The accounts will require that the owner of the interceptor drone system will be verified prior to using the application which also helps control who will have access to this security system.

The overall security of the system is very important for us. As one can imagine, having an interceptor drone or even a fleet of them could be used with malicious intent by some. Therefore, both the application and the ground control stations would need to be secured in order to prevent such attacks from taking place. This can be done by requiring the users to make an account for using the application and also having the users verified when installing the interceptor drone system as described above. Moreover, the protocols used by the drones to send data to the ground station will be secured to avoid any possible attacks. Also the communication between all the subsystems will happen in a network which will be secured and closely monitored for suspicious traffic. Although we strive to build a package that is as secure as possible, this will not be the main point of this project and in the following we will concentrate on application’s user interface.

Home Page

This is where the users can have an overview of all the interceptor drones in their fleet. The screen displays an informative picture which is representative for each drone. By clicking on the drone’s card, the user will be taken to the drone’s Status page. The Home page also has a bottom navigation bar to all the other pages in the application: Security, Location and Settings. When the user will login into the application, the Home page will be the first screen that will show up.

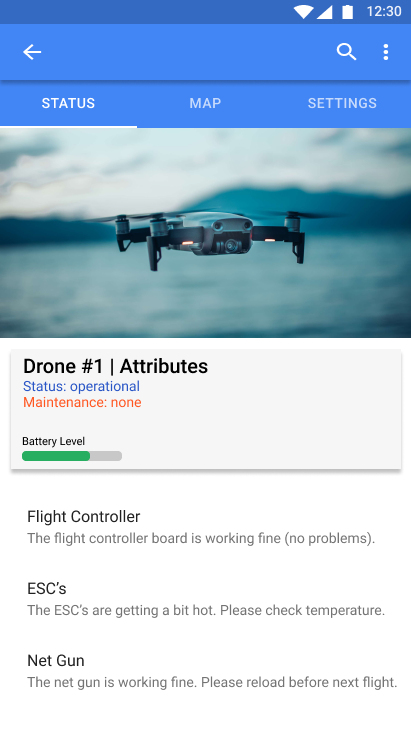

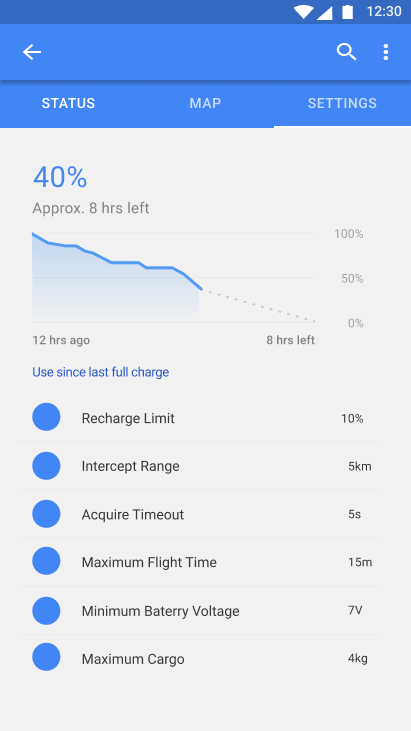

Status Page

Each drone has a status page in the app. This can be accessed by clicking on a drone from the Home page. From this page, users can view whether the drone is operational or not. Any maintenance problems or error logs are also displayed here. This will be of tremendous help for the personnel who will have to take care and maintain the drone fleet. Moreover, the battery level for the drone is also displayed on this page. Each individual subsystem of the drone, such as motors, electronic speed controllers, flight controller, cameras or the net gun will have their operational status displayed on this page.

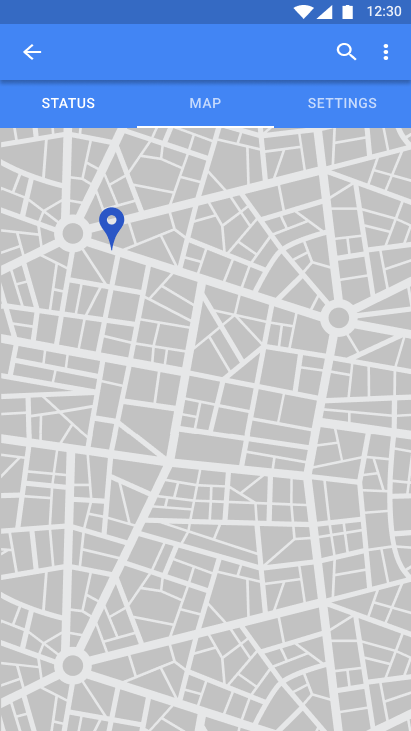

Map Page

The Map page can be accessed from the drone’s status page. On the Map page the current location of the drone is displayed. The map can be dragged around for a better view of where the drone is located. This is helpful to not only monitor the progress of the interceptor drone during a mission, but also helps in situations when the drone might not be able to successfully fly back to the base in which case it would need to be recovered from its last known location.

Settings Page

The Settings page can be accessed from the drone’s status page. On the settings page the users can select different configurations for the drone and also view a number of graphs displaying various useful information such as battery draining levels.

Security Page

This page can be accessed from the Home page by clicking on the Security page button in the bottom navigation menu. From this page users can change different settings which are related to the security of the protected asset such as an airport or a governmental institution. For example, the no-fly zone coordinates can be configured from here together with the sensitivity levels for the whole detection system.

Radar Map Page

This page can be accessed from the Home page by clicking on the Radar Map page button in the bottom navigation menu. On this page, the users can view the location of all the drones nicely displayed on a radar like map. This is different from the drone’s Map page since it shows where all the drones in the fleet are positioned and gives a better overall view of the whole system. It also displays all the airplane related traffic from around the airport.

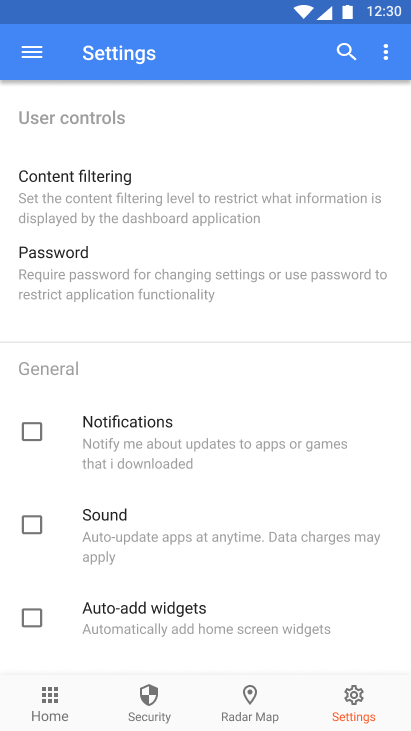

System Settings Page

This page can be accessed from the Home page by clicking on the Settings page button in the bottom navigation menu. From this page users can change different settings which are not related to the security of the system. These can be things such as assigning different identifiers for the drones to be displayed on the home page and also changing the configuration settings for the communication between the drones and the ground stations.

User Testing

For testing whether the application and its user interface are intuitive and easy to use, a questionnaire was built. The main purpose for this was to see what needed to be improved for the application to be useful for the end users. We will provide both the questionnaire and its results once the user testing phase is finished for the application.

State of the Art

In this section the State of the Art (or SotA) concerning our project will be discussed.

Tracking/Targeting

To target a moving target from a moving drone, a way of tracking the target is needed. A lot of articles on how to do this, or related to this problem have been published:

- Moving Target Classification and Tracking from Real-time Video. In this paper describes a way of extracting moving targets from a real-time video stream which can classify them into predefined categories. This is a useful technique which can be mounted to a ground station or to a drone and extract relevant data of the target.[13]

- Target tracking using television-based bistatic radar. This article describes a way of detecting and tracking airborne targets from a ground based station using radar technology. In order to determine the location and estimate the target’s track, it uses the Doppler shift and bearing of target echoes. This allows for tracking and targeting drones from a large distance. [14]

- Detecting, tracking, and localizing a moving quadcopter using two external cameras. In this paper a way of tracking and localizing a drone using the bilateral view of two external cameras is presented. This technique can be used to monitor a small airspace and detect and track intruders. [15]

- Aerial Object Following Using Visual Fuzzy Servoing. In this article a technique is presented to track a 3D moving object from another UAV based on the color information from a video stream with limited info. The presented technique as presented is able to do following and pursuit, flying in formation, as well as indoor navigation. [16]

- Patent for an interceptor drone tasked to the location of another tracked drone. This patent proposes a system which includes LIDAR detection sensors and dedicated tracking sensors. [17]

- Patent for detecting, tracking and estimating the speed of vehicles from a moving platform. This patent proposes an algorithm operated by the on-board computing system of an unmanned aerial vehicle that is used to detect and track vehicles moving on a roadway. The algorithm is configured to detect and track the vehicles despite motion created by movement of the UAV.[18]

- Patent for scanning environments and tracking unmanned aerial vehicles. This patent refers to systems and methods for scanning environments and tracking unmanned aerial vehicles within the scanned environments. It also provides a method for identifying points of interest in an image and generating a map of the region. [19]

- Algorithms based on Multiplayer Differential Game Theory, such as two-player decomposition approach, maximum principle approach and minimum-time decomposition approach are presented, each arriving to an efficient way of intercepting an attacking UAV but focusing on optimizing a different variable based on the numbers of drones controlled and attacking the UAV. [20]

Autonomous flying

- Patent for flight control using computer vision. This patent provides methods for computing a three-dimensional relative location of a target with respect to the reference aerial vehicle based on the image of the environment. [21]

- Cooperative Control Method Algorithm. This paper presents experimental results for the simultaneous interception of targets by a team of UAV’s. It includes an overview of the co-operative control strategy which can also be used in this project’s drones. [22]

- Framework for Autonomous On-board Navigation. This article presents a framework for independent autonomous flying of a drone solely based on its onboard sensors. In this framework, the high-level navigation, computer vision and control tasks are carried out in an external processing unit. [23]

- Towards a navigation system for autonomous indoor flying. This article provides a framework for autonomous indoor flying for small UAV’s derived from existing systems for ground based robots. This system can be utilized for indoor drone interception where dodging objects and humans is one of the most important features. [24]

- Mission path following for an autonomous unmanned airship. In this project (AURORA) multiple flight path following techniques through a set of pre-defined points are described and compared through simulation. The tests were conducted both with and without wind to show the performance of the controllers. [25]

- Patent for autonomous tracking and surveillance. This patent refers to a method of protecting an asset by imposing a security perimeter around it which is further divided in a number of zones protected by unmanned aerial vehicles.[26]

Stopping drones

- One way of catching a drone is by shooting at it with a net. Extensive research has been done on shooting nets, mainly for wildlife purposes. [27][28]

- Looking at drones shooting nets specifically, pneumatic launchers have been implemented successfully. [29]

- Electromagnetic Launchers present another opportunity for launching a net to another drone. This article explains the mathematical model of such a system and shows the power of electromagnetic launchers, which offer very high acceleration speeds.[30]

- This paper shows another option for shooting a net is using a hybrid pneumatic-electromagnetic launcher, giving the mathematical model of this system and simulation results. It shows that a hybrid system offers a huge control in the acceleration, more so than a simple pneumatic launcher or an electromagnetic one. [31]

General design of drones

- Design and control of quadrotors with application to autonomous flying. This paper describes a design of a micro quadrotor, its simulation and linear and nonlinear control techniques. The techniques presented in this paper are broadly applicable and can be used in other drone environments, like drone interception activities. [32]

- Aerodynamics and control of autonomous quadrotor helicopters in aggressive maneuvering. This article improves on previous work on aerodynamic effects impacting quadrotors. These are used to develop new control techniques that allow for more aggressive maneuvering. This is also useful in the pursuit of another agile drone or UAV. [33]

One big challenge surrounding drones is that their flight time is really limited. A way to prevent this and to have drones constantly surveilling the area they are programmed to is with autonomous mid-air battery swapping. [34]

Other

Although the use of drones for intervention is not directly military, this application can be seen as military. In a paper by Bradley Jay Strawser, the duty to employ UAV’s is discussed. It describes why there is nothing wrong in principle with using a UAV’s. [35]

There is also an existing company, in Delft, that is making drone intercepting drones called Delft Dynamics and they have built the DroneCatcher[10]

References

- ↑ Allianz Global Corporate & Specialty (2016). Rise of the Drones Managing the Unique Risks Associated with Unmanned Aircraft Systems

- ↑ Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) (2017). UAS Airborne Collision Severity Evaluation Air Traffic Organization, Washington, DC 20591

- ↑ From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (2018). Gatwick Airport drone incident Wikipedia

- ↑ Pamela Gregg (2018). Risk in the Sky? University of Dayton Research Institute

- ↑ From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (2019). Unmanned aerial vehicle Wikipedia

- ↑ From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (2019). Serbia v Albania (UEFA Euro 2016 qualifying) Wikipedia

- ↑ Alex Hern, Gwyn Topham (2018). How dangerous are drones to aircraft? The Guardian

- ↑ OpenWorks Engineering [1]

- ↑ MALOU-tech [2]

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Delft Dynamics DroneCatcher

- ↑ D. Lee, J. Zhou, W. Tze Lin Autonomous battery swapping system for quadcopter (2015)

- ↑ C. Teuliere, L. Eck, E. Merchand (2011) Chasing a moving target from a flying UAV 2011 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems

- ↑ A.J. Lipton, H.Fujiyoshi, R.S. Patil Moving target classification and tracking from real-time video (1998) Proceedings Fourth IEEE Workshop on Applications of Computer Vision. WACV'98 (Cat. No.98EX201)

- ↑ P.F. Howland Target tracking using television-based bistatic radar (1999) IEE Proceedings - Radar, Sonar and Navigation Volume 146, Issue 3 p. 166 – 174

- ↑ M. Dreyer, S. Raj, S. Gururajan, J. Glowacki Detecting, Tracking, and Localizing a Moving Quadcopter Using Two External Cameras (2018) 2018 Flight Testing Conference, AIAA AVIATION Forum, (AIAA 2018-4281)

- ↑ O. Méndez, M. Ángel, M. Bernal, I. Fernando, C. Cervera, P. Alvarez, M. Alvarez, L. Luna, M. Luna, C. Viviana Aerial Object Following Using Visual Fuzzy Servoing (2011)

- ↑ Brian R. Van Voorst (2017). Intercept drone tasked to location of lidar tracked drone U.S. Patent No. US20170261604A1. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office

- ↑ Eric Saund Christopher. Paulson Gregory. Burton Eric Peeters. (2014). System and method for detecting, tracking and estimating the speed of vehicles from a mobile platform U.S. Patent No. US20140336848A1. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office

- ↑ Asa Hammond Nathan. Schuett Naimisaranya Das Busek. (2016). Scanning environments and tracking unmanned aerial vehicles U.S. Patent No. US20160292872A1. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office

- ↑ Johan M. Reimann USING MULTIPLAYER DIFFERENTIAL GAME THEORY TO DERIVE EFFICIENT PURSUIT-EVASION STRATEGIES FOR UNMANNED AERIAL VEHICLES (2007) School of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology

- ↑ Guy Bar-Nahum. Hong-Bin Yoon. Karthik Govindaswamy. Hoang Anh Nguyen. (2018). Flight control using computer vision U.S. Patent No. US20190025858A1. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office

- ↑ Timothy W. McLain and Randal W. Beard, Jed M. Kelsey Experimental Demonstration of Multiple Robot Cooperative Target Intercept (2007)

- ↑ J. J. Lugo, A. Zell Framework for Autonomous On-board Navigation with the AR.Drone (2013)

- ↑ S. Grzonka, G. Grisetti, W. Burgard Towards a navigation system for autonomous indoor flying(2009)

- ↑ J.R. Azinheira, E. Carneiro de Paiva, J.G. Ramos, S.S. Beuno Mission path following for an autonomous unmanned airship (2000)

- ↑ Kristen L. Kokkeby Robert P. Lutter Michael L. Munoz Frederick W. Cathey David J. Hilliard Trevor L. Olson (2008). System and methods for autonomous tracking and surveillance U.S. Patent No. US20100042269A1. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office

- ↑ STEPHEN L. WEBB, JOHN S. LEWIS, DAVID G. HEWITT, MICKEY W. HELLICKSON, FRED C. BRYANT Assessing the Helicopter and Net Gun as a Capture Technique for White‐Tailed Deer (2008) The Journal of Wildlife Management Volume 72, Issue 1,

- ↑ Andrey Evgenievich Nazdratenko (2007) Net throwing device U.S. Patent No. US20100132580A1. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office

- ↑ Mohammad Rastgaar Aagaah, Evandro M. Ficanha, Nina Mahmoudian (2016) Drone with pneumatic net launcher U.S. Patent No. US20170144756A1. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office

- ↑ Leubner, Karel & Laga, Radim & Dolezel, Ivo. (2015) Advanced Model of Electromagnetic Launcher Advanced Model of Electromagnetic Launcher. Advances in Electrical and Electronic Engineering. 13. 223-229. 10.15598/aeee.v13i3.1419

- ↑ Domin, Jaroslaw & Kluszczyński, K. (2013) Hybrid pneumatic-electromagnetic launcher Hybrid pneumatic-electromagnetic launcher - general concept, mathematical model and results of simulation. 89. 21-25.

- ↑ S. Bouabdallah, R. Siegwart Design and control of quadrotors with application to autonomous flying (2007)

- ↑ H. Huang, G. M. Hoffmann, S. L. Waslander, C. J. Tomlin Aerodynamics and control of autonomous quadrotor helicopters in aggressive maneuvering (2009)

- ↑ Jacobsen, Reed; Ruhe, Nikolai; and Dornback, Nathan Autonomous UAV Battery Swapping (2018)

- ↑ Bradley Jay Strawser Moral Predators: The Duty to Employ Uninhabited Aerial Vehicles Journal of Military Ethics, Volume 9, 2010 – Issue 4