PRE2019 3 Group8: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 113: | Line 113: | ||

==Concept== | ==Concept== | ||

The robot will approach | The main idea of the robot is that it has a screen on which it can display the online learning platform are developing, and that it is mobile enough to approach children in class. The robot will approach the kids, because children might fear situations in which they face criticism or in which they feel they might make themselves look ridiculous to others, which is a very prevalent social anxiety children have to deal with (Möller & Bögels, 2017). This might result in the fact that our target students might be less inclined to let the teacher (or the robot, for that matter) know they did not understand a concept out of fear of feeling criticized. Moreover, a positive relation is found between intrinsic motivation and academic achievement in young children (Broussard & Garrison, 2004). This implies that our target group—low-IQ children—will have less motivation to study and improve at school. Therefore, the robot should also be able to generate motivation in children to make them eager to study with the robot. | ||

https://spectrum.ieee.org/automaton/robotics/home-robots/haru-an-experimental-social-robot-from-honda-research → “Our goals were to design a personal robot that people would really love. Something that people really felt a connection with.” Dus de kinderen met een laag IQ halen intrinsic motivation uit het communiceren met de robot en daardoor wordt leren leuker voor hen. | https://spectrum.ieee.org/automaton/robotics/home-robots/haru-an-experimental-social-robot-from-honda-research → “Our goals were to design a personal robot that people would really love. Something that people really felt a connection with.” Dus de kinderen met een laag IQ halen intrinsic motivation uit het communiceren met de robot en daardoor wordt leren leuker voor hen. | ||

In order for the robot to approach the student, it will need to be able to draw their attention appropriately. According to Torta (2014), the most common interaction cues in joint attention are gazing movements and pointing gestures. Waving to get attention is generally considered to be more pleasant and friendly than making eye contact, and it is processed faster than blinking. However, it might be the case that the robot’s physical shape does not allow it to wave. In this case, it should be noted that just looking at a person might be considered not very friendly, according to Torta (2014). Therefore, an auditory cue should be integrated, such as the robot’s saying “Hello” to draw attention. | In order for the robot to approach the student, it will need to be able to draw their attention appropriately. According to Torta (2014), the most common interaction cues in joint attention are gazing movements and pointing gestures. Waving to get attention is generally considered to be more pleasant and friendly than making eye contact, and it is processed faster than blinking. However, it might be the case that the robot’s physical shape does not allow it to wave. In this case, it should be noted that just looking at a person might be considered not very friendly, according to Torta (2014). Therefore, an auditory cue should be integrated, such as the robot’s saying “Hello” to draw attention. | ||

== State-of-the-Art == | == State-of-the-Art == | ||

Revision as of 10:52, 2 March 2020

Group Members

| Name | Study | Student ID |

|---|---|---|

| Teis Arets | Psychology & Technology | 1261991 |

| Tom Bergmans | Psychology & Technology and Electrical Engineering | 1253565 |

| Nynke Boonstra | Psychology & Technology | 1251155 |

| Bob Hofstede | Psychology & Technology | 0950282 |

| Emile Merle | Computer Science | 1244746 |

Plan

Abstract

In this article one can read about our literature study towards a study buddy. The results are used to come up with recommendations for designing a study buddy. The study buddy can be used by children who have difficulties with keeping pace of fellow scholars.

Planning

Each group has plan ready after Week 1, Plan contains:

- subject,

- objectives,

- users,

- state-of-the-art,

- approach,

- planning,

- milestones,

- deliverables,

- who will do what

Milestones

- Decide upon a subject.

- Write the introduction and the problem statement.

- Describe the users and their needs.

- Describe the approach.

- Search and read papers about the current state of the art.

- Make a summary of the papers about the current state of the art.

- Narrow down the scope of the project.

- Create interview scheme for teachers.

- Conduct the interviews with teachers.

- Make personas and scenarios to illustrate the value of the project.

- Start looking into ways to program the online learning platform and how to make virtual assistants.

- Start writing down the technical content in the report.

- Integrate the scenarios and personas into development of the learning platform.

- Work out, finalize, and refine the online learning platform, and make sure it can be displayed on an interface with a touchscreen.

- Let elementary school children interact with the system to assess the system’s efficacy.

- Use these results to write the results section and the discussion.

- Write the conclusion.

- Prepare a presentation about the robot.

- Give the presentation about the robot.

- Complete the Wiki page.

Deliverables

- A complete and coherent Wiki page concerning the development of the online learning platform designed to teach less intelligent elementary school children.

- A prototype of the virtual learning system that shows an explanation of, and an examination of fractions.

- A presentation about the study of how to design a study buddy

Approach

In order to find out how the perfect study buddy system should be designed, we will perform a literature study about the needs of feeble-minded children in elementary school. Furthermore, elementary school teachers will be interviewed to assess to what extent the teachers believe the virtual study buddy system will be effective, and to find out what functions and characteristics the system should have in order to become effective. We will use this information to create several personas that represent the primary users. Based on these persona’s and additional literature, we come up with a digital learning platform that allows students to select from an array of topics the topic the need more help with. We will create only part of this platform that will explain, elaborate on, and test the topic of fractions in primary school arithmetic. We will then test this prototype of the virtual platform with real elementary school kids, after which we will let them evaluate the system’s effectiveness. This will show us what can be improved further afterwards.

Introduction

Since the introduction of the Dutch “Wet Passend Onderwijs” in 2014, elementary school children with physical or mental disabilities are stimulated to follow regular education as much as possible (“Scholen voor speciaal onderwijs bezwijken onder wachtlijsten,” 2019). However, according to Wim Ludeke of the Landelijk Expertisecentrum Speciaal Onderwijs (LESCO), the number of children applying for a custom form of education is increasing. The reason is that, as a result of the current lack of elementary school teachers (Traag, 2018), teachers of “regular schools” do not have the time and resources to support these children, and thus they are sent back to schools with extra support. In the Netherlands, there are approximately 2.2 million people considered to have low intellectual ability (“Prevalentie van verstandelijke beperking,” 2020), which means they have an IQ-score between 70 and 85 (Bexkens, Petry, Graas, & Huizinga, 2018). According to the CBS’ population counter (2019), the actual amount of Dutch inhabitants is 17,420,249. This means that about 12.5% of the Dutch inhabitants is considered feeble-minded, or less intellectually capable. In a letter to the Dutch Parliament, the minister for elementary and secondary school education wrote that primary school classes consist of 23.0 children, on average (Slob, 2019). Between the age of 4 and 11, there are about 35,000 children that get a special kind of education (“Speciaal basisonderwijs,” 2019). Furthermore, there are about 1,500,000 children in total that get primary education (“Ontwikkeling van het aantal leerlingen,” 2018). Taking these numbers into account, each class in regular primary education is bound to accommodate at least two children that are feeble-minded, on average. This means two children that require extra attention from their teacher during their education, attention which cannot be given to them in the current state of Dutch education.

Subject

A study buddy robot that helps elementary school children with a relatively low IQ understand and practice material taught in class better.

Problem statement

This introduces the problem that children with a need for special education in schools that provide regular education cannot receive an optimal tuition. The focus in this research will be on feeble-minded elementary school children. These children often experience difficulties with learning. For example, they often fail to understand a novel concept the first time it is explained in class, because of which they might need an extra, more elaborate explanation of the concept (Ahmad, Mubin, & Orlando, 2016). In circumstances like this, the teacher often lacks the time to provide this kind of extra tuition, but a robot providing a virtual learning platform in the class could repeat it as many times as necessary, and elaborate on the content as much as needed.

Objectives

The aim of our literature study is to define a robot that can act as a study buddy to help feeble-minded children in elementary school keep up with the pace of fellow students. Our goal is to develop a prototypical, virtual platform displayed on the robot’s interface that can repeat, elaborate on, and test topics of interest that feeble-minded children did not understand the first time a teacher explained it to them. Therefore, we aim to make the regular Dutch education more effective and accessible for elementary school children with an IQ below average between 70 and 85.

Users

Eventually the user group will consist of all scholars and/or students. For now, the focus is only primary school students of the Dutch 'group five and six', those students are normally between 7 and 9 years old. Users that will use the app the most and the app is designed for, are scholars with problems concerning concentration, like autistic children. Other examples are scholars that are too smart and don’t feel motivated anymore to study.

Primary Users

The primary user in this report will be defined as the person that actually works and interacts with the study buddy robot. Therefore, the primary user will certainly be the somewhat less cognitively capable elementary school students that need some extra guidance during class. After the teacher is done explaining some new content, the robot will approach the student and briefly quizzes them on the topic just explained to see if they perform well enough to indicate they get the basic content of what was explained.

Furthermore, the teachers are considered to be a primary user, because they need to specify which topic was treated in class in order for the robot to approach the children with the right study material. So, the teacher also works with the study buddy first-hand in terms of setting up the robot’s study plan. Moreover, the teacher will keep track of the students’ progress after working with the study robot.

Secondary Users

Secondary users of the teaching robot are classified as people who may be indirectly influenced by the system in some way. In this case, where we assume a class in regular education with a relatively small amount of feeble-minded students that require a study buddy robot, the secondary user would be the classmates that are not assigned a study robot. An influence of a peer’s study robot on classmates might be a disruption of classmates’ concentration due to sound expressed by the robot during one of its explanations, or simply due to distracting images on the robot’s interface.

Requirements

The virtual study buddy shall:

- have an touchscreen as an interface to communicate the content of the class with the student.

- be able to express emotion by the virtual robot.

- understand the emotional state of the student and communicate accordingly.

- be able to keep track of the progress of the user.

- look human-like and kind

Concept

The main idea of the robot is that it has a screen on which it can display the online learning platform are developing, and that it is mobile enough to approach children in class. The robot will approach the kids, because children might fear situations in which they face criticism or in which they feel they might make themselves look ridiculous to others, which is a very prevalent social anxiety children have to deal with (Möller & Bögels, 2017). This might result in the fact that our target students might be less inclined to let the teacher (or the robot, for that matter) know they did not understand a concept out of fear of feeling criticized. Moreover, a positive relation is found between intrinsic motivation and academic achievement in young children (Broussard & Garrison, 2004). This implies that our target group—low-IQ children—will have less motivation to study and improve at school. Therefore, the robot should also be able to generate motivation in children to make them eager to study with the robot.

https://spectrum.ieee.org/automaton/robotics/home-robots/haru-an-experimental-social-robot-from-honda-research → “Our goals were to design a personal robot that people would really love. Something that people really felt a connection with.” Dus de kinderen met een laag IQ halen intrinsic motivation uit het communiceren met de robot en daardoor wordt leren leuker voor hen.

In order for the robot to approach the student, it will need to be able to draw their attention appropriately. According to Torta (2014), the most common interaction cues in joint attention are gazing movements and pointing gestures. Waving to get attention is generally considered to be more pleasant and friendly than making eye contact, and it is processed faster than blinking. However, it might be the case that the robot’s physical shape does not allow it to wave. In this case, it should be noted that just looking at a person might be considered not very friendly, according to Torta (2014). Therefore, an auditory cue should be integrated, such as the robot’s saying “Hello” to draw attention.

State-of-the-Art

Haru

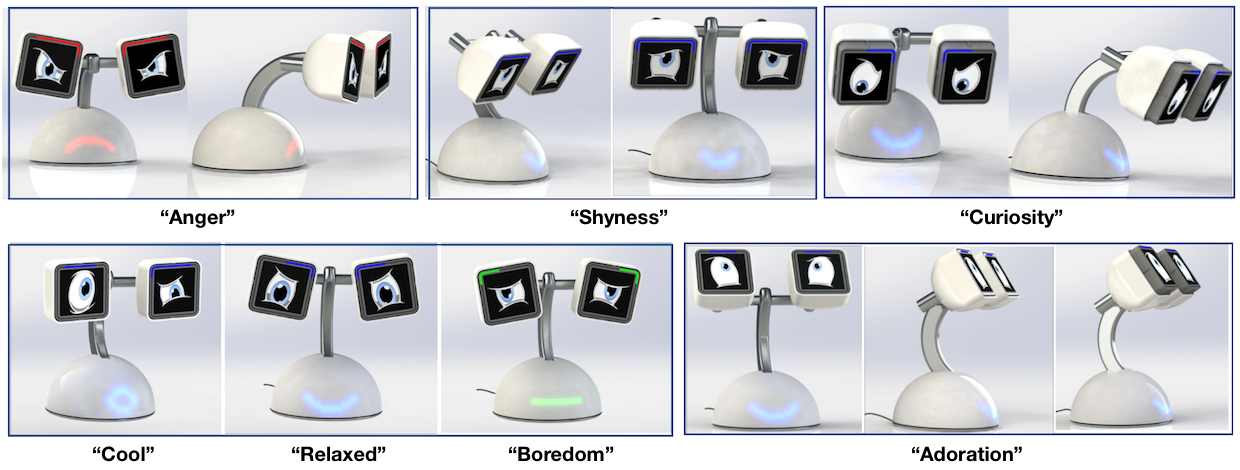

The image on the right shows the desktop robot Haru, designed to be a social companion robot for people of any age. In designing Haru, empathy was a key consideration, and it can recognize facial affect and signal emotion through body movements and visual elements such as eyes and color (Gomez, Szapiro, Galindo, & Nakamura, 2018). This robot can therefore interact with people appropriately due to the incorporation of current emotions in the interaction, which allows for communication according to the emotional state of the person it interacts with. To signal a feeling of proper understanding, the robot should be able to express a wide range of emotions. This range is visualized in the figure below:

Because of the robot’s anthropomorphic shape, it can facilitate human-robot interaction, because it “incorporates the underlying principles and expectations people use in social settings in order to fine-tune the social robot’s interaction with humans” (Duffy, 2003).

However, Haru does not have a voice yet (Aylett, Sutton, & Vazquez-Alvarez, 2019).This means a robot like this is purely useful for showing information on its screens that does not require additional sound, such as chapters from a book. If Haru would be used for the implementation of the study buddy, we would have to record voices ourselves. Furthermore, Haru is a desktop robot, so it would not be able to approach people, as we aspire to achieve with the study buddy.

Haru would be a useful foundation for our study buddy, because it is so much focused on empathy, and recognizing and signaling emotion. If it were to approach children in class, the robot needs to do so keeping in mind it is interacting with children that require a unique, individual approach. Furthermore, the two interfaces Haru possesses to display its eyes can be used to display the virtual learning platform on, so no external interfaces are required.

Other sources

In this section, research is done to investigate what is already known about (robotic) study buddies. Twenty-five articles are found, each article is shortly described to end up with an overview about different studies on study buddies.

1. Ahmad, M. I., Mubin, O., Shahid, S., & Orlando, J. (2017). Emotion and memory model for a robotic tutor in a learning environment.

- A robot tried to teach children vocabulary, while the children were playing snake. The robot was either giving positive, negative or neutral feedback. The result of the positive feedback had a significant effect compared to the other two in addition the robots helped to learn the children learn vocabulary.

2. Ahmad, M. I., Mubin, O., & Orlando, J. (2016). Understanding behaviours and roles for social and adaptive robots in education: Teacher’s perspective.

- The purpose of this study is to not only understand teacher's opinion on the existing effective social behaviours and roles but also to understand novel behaviours that can positively influence children performance in a language learning setting.

3. Andrews, J. and Clark, R. (2011). Peer mentoring works! Birmingham: Aston University.

- This report draws on the findings of a three year study into peer mentoring conducted at 6 Higher Education Institutions (HEIs). The research findings provide empirical evidence that peer mentoring works.

4. Arnold, L., Lee, K.J., & Yip, J.C. (2016) Co-designing with children: An approach to social robot design.

- The study let children co-design during their process of making a Friend Robot. It turns out that including children in the design process is a way to gain unique insights. Several of the children said that they would want their friend robot to be small and portable.

5. Edwards, A; Edwards, C; Spence, P; Harris, C; Gambino, A (2016), Robots in the classroom: Differences in students’ perceptions of credibility and learning between “teacher as robot” and “robot as teacher”.

- College students rated the credibility of a teleoperated robot and an autonomous social robot acting as a teacher for the same lecture. Results showed that while the teleoperated robot was considered more credible, the overall teaching was of the same level and students are willing to follow lectures of autonomous robots.

6. E.Hyun ; H.Yoon ; S. Son (2010) Relationships between user experiences and children's perceptions of the education robot.

- To help with better studying, the robot should be placed/interacted with in a classroom rather than a hallway or office. The results were better when there was a two-way interaction, which means using the touchscreen and listening to the robot's voice.

7. Fachantidis, N., Dimitriou, A. G., Pliasa, S., Dagdilelis, V., Pnevmatikos, D., Perlantidis, P., & Papadimitriou, A. (2017). Android OS mobile technologies meets robotics for expandable, exchangeable, reconfigurable, educational, STEM-enhancing, socializing robot.

- A socially assistive robot is being constructed to represent a companion of the student, motivating and rewarding him. The paper addresses existing prior-art and how an android OS smartphone will address the design requirements.

8. Feil-Seifer, D., & Matarić, M. J. (2011). Socially assistive robotics. IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine, 18(1), 24-31.

- The paper aims to probe the need of an assistive robot that makes reading process less challenging.

abstract.

9. Fridin, M. (2014). Storytelling by a kindergarten social assistive robot: A tool for constructive learning in preschool education. Computers & education, 70, 53-64.

- The experiment in this paper was designed to examine how KindSAR(Kindergarten social staff) can be used to engage preschool children in constructive learning, the basic principe of constructivist eductaion is that learning occurs when the learner is actively involved in a process of knowledge construction.

10. Janssen, J.B., van der Wal, C.C., Neerincx, M. (2016). Motivate to learn: Effects of performance adaptation on child motivation of robot interaction

- Long-term interaction between children and robots requires the child to have a bond with the robot. Specifically for children with diabetes, robot interaction could be a valuable addition as support for their daily struggles. Results from the free-choice period showed that motivation of children that interacted with the adaptive robot was significantly higher compared to the non-adaptive robot.

11. Kim, Y., Smith, D., Kim, N., & Chen, T. (2014). Playing with a Robot to Learn English Vocabulary

- Through multiple observations of child-robot play in situ, it was noted that children easily learned how to interact with the robot and showed sustained interest and engagement in the curricular activities with the robot

12. Lee E.K., & Lee Y.J. (2008). Elementary and Middle School Teachers’, Students’ and Parents’ Perception of Robot-Aided Education in Korea.

- In Korea, robot-aided education has been studied. It was shown that robot-aided education was friendlier than other media-assisted education and enhanced children’s motivation. The perceptions and needs of intelligent educational service robot among teachers, students and parents in Korea were surveyed. In this study, it was found that they have a positive perception of the use of robots in schools. However, they do not want to use the robot as a teacher.

13. Leite, I., Pereira, A., Castellano, G., Mascarenhas, S., Martinho, C., & Paiva, A. (2011, June). Social robots in learning environments: a case study of an empathic chess companion.

- For the system used in this paper a multimodal system for predicting and modeling some of the children’s affective states is currently being trained using a corpus. With this model a personalised learning experience by adapting the robot’s empathy to the needs of the child is modeled.

14. Leyzberg, D; Spaulding, S ; Scassellati, B (2014), Personalizing Robot Tutors to Individuals’ Learning Differences, in 2014 9th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI)

- A robot tutor gives either general or personalized advice. The study shows that there is a one-sigma increase in results with personalized advice, signifying that the personalized advice of the robot can give results no matter how small.

15. Leyzberg, D; Spaulding, S ; Scassellati, B; Toneva, M (2012); The Physical Presence of a Robot Tutor Increases Cognitive Learning Gains, Department of Computer Science, Yale University

- 100 students were tasked to solve a series of puzzles, with robot tutors giving varying degrees and methods of advice. Results showed that the group of students with the physical presence of the robot giving personalized advice were the better group.

16. Meghdari, A., Shariati, A., Alemi, M., Vossoughi, G. R., Eydi, A., Ahmadi, E., Tahami, R. (2018). Arash: A social robot buddy to support children with cancer in a hospital environment.

- The social robot Arash is for educational and therapeutic involvement in a pediatric hospital to entertain, assist and educate cancer patients. Two experiments were done to evaluate the acceptance and involvement of the robot, the obtained results confirm high engagement and interest of pediatric cancer patients with the constructed robot.

17. Robins, B.; Dautenhahn, K; Te Boekhorst, R. & Billard, A. (2005); Robotic assistants in therapy and education of children with autism: can a small humanoid robot help encourage social interaction skills? In Universal Access in the Information Society

- This study let children with autism interact with both robots and humans. Results showed that, after first interacting with robots, their social skills were better when interacting with humans.

18. Shahid, S., Krahmer, E., & Swerts, M. (2014). Child–robot interaction across cultures: How does playing a game with a social robot compare to playing a game alone or with a friend?

- This study let children interact with social robots. The children played games with iCat, it turns out that the children prefer playing with iCat above playing alone. However, the children do even more prefer playing with friends.

19. Serholt, S; Basedow, C; Barendregt, W; Obaid, M (2014), Comparing a humanoid tutor to a human tutor delivering an instructional task to children

- The study compares two groups of children creating a LEGO construction, one with a human instructor and one with a robot instructor. The results show equal performance, but different attitudes: children ask more questions to the human tutor, but are more eager to do well with the robot tutor.

20. Stephens, H., & Jairrels, V. (2003). Weekend Study Buddies: Using Portable Learning Centers.

- The use of the study buddy may encourage parents to be more involved and if the children enjoy the study buddy at school it may extend that enjoyment at home.The student buddy may serve as an additional tool for individualizing instruction and enhancing the achievement for all students.

21. Sinoo, C., van der Pal, S., Blanson Henkemans, O.A, Keizer, A., Bierman, B.P.B., Looije, R. & Neerincx, M.A. (2018). Friendship with a robot: Children’s perception of similarity between a robot’s physical and virtual embodiment that supports diabetes self-management.

- The PAL project develops a conversational agent with a physical (robot) and virtual (avatar) embodiment to support diabetes self-management of children ubiquitously. Their conclusions are that children felt stronger friendship towards the physical robot than towards the avatar. The more children perceived the robot and its avatar as the same agency, the stronger their friendship with the avatar was. The stronger their friendship with the avatar, the more they were motivated to play with the app and the higher the app scored on usability.

22. Thalluri, J., O'Flaherty, J.A., & Shepherd, P.L., (2014). Classmate peer-coaching: "A Study Buddy Support scheme".

- The study investigated the effects of a human study buddy. The students with a study buddy scored higher on a test compared to the ones without.

23. Verner, I; Polishuk, A; Krayner, N (2016), Science Class with RoboThespian: Using a Robot Teacher to Make Science Fun and Engage Students, in IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine (Volume: 23, Issue: 2, June 2016)

- the humanoid robot RoboThespian gives a science lecture to children from grades 5-7 in two different environments, to check the perception of the robot by the children. The results are positive, and the educational goals attained.

24. Werry, I. Dautenhahn, K. (1999) Applying Mobile Robot Technology to the Rehabilitation of Autistic children.

- The paper discusses the background and major motivations which are driving the AuRoRA--(Autonomous Robotic platform as a Remedial tool for children with Autism) research project.In conclusion, robots can make a valid contribution in the process of rehabilitation and have the potential to make a contribution in the area of autism.

25. Werry, I., Dautenhahn, K., Harwin, W. (2001) Investigating a Robot as a Therapy Partner for Children with Autism.

- The AuRoRA project is investigating the possibility of using a robotic platform as a therapy aid for children with autism. The results thus far are encouraging in that they indicate that the children not only enjoy interacting and playing with the robot at various levels, but that they focus attention on the robot for longer than the toy truck. The children seem able to form very simple bonds with the robot and even to understand the basic interactions involved.

References

Aylett, M. P., Sutton, S. J., & Vazquez-Alvarez, Y. (2019, August). The right kind of unnatural: designing a robot voice. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Conversational User Interfaces (pp. 1-2).

Bevolkingsteller. (2019). Retrieved from https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/visualisaties/bevolkingsteller

Bexkens, A., Petry, K., Graas, D., & Huizinga, M. (2018). Kinderen met een licht verstandelijke beperking binnen het regulier onderwijs: Een visie op M-decreet en Passend onderwijs. Zorgbreed, 59, 7.

Broussard, S. C., & Garrison, M. B. (2004). The relationship between classroom motivation and academic achievement in elementary‐school‐aged children. Family and consumer sciences research journal, 33(2), 106-120.

Duffy, B. R. (2003). Anthropomorphism and the social robot. Robotics and autonomous systems, 42(3-4), 177-190.

Gomez, R., Szapiro, D., Galindo, K., & Nakamura, K. (2018, February). Haru: Hardware design of an experimental tabletop robot assistant. In Proceedings of the 2018 ACM/IEEE international conference on human-robot interaction (pp. 233-240). Scholen voor speciaal onderwijs bezwijken onder wachtlijsten. (2019). Retrieved from https://nos.nl/artikel/2303246-scholen-voor-speciaal-onderwijs-bezwijken-onder-wachtlijsten.html

Möller, E., & Bögels, S. (2017). Sociale angst bij kinderen: de rol van ouders. In Pedagogiek in beeld (pp. 265-274). Bohn Stafleu van Loghum, Houten. Traag, T. (2018). Leerkrachten in het basisonderwijs. Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek (CBS).

Ontwikkeling van het aantal leerlingen in het primair onderwijs. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.onderwijsincijfers.nl/kengetallen/po/leerlingen-po/aantallen-ontwikkeling-aantal-leerlingen

Prevalentie van verstandelijke beperking. (2020). Retrieved from https://www.volksgezondheidenzorg.info/onderwerp/verstandelijke-beperking/cijfers-context/huidige-situatie#node-prevalentie-van-verstandelijke-beperking

Slob, A. (2019). Gemiddelde groepsgrootte in het basisonderwijs. Retrieved from https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/kamerstukken/2019/06/17/kamerbrief-over-groepsgrootte-en-leerling-leraarratio-in-basisonderwijs-2018

(Speciaal) basisonderwijs en speciale scholen; leerlingen, schoolregio. (2019). Retrieved from https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/71478ned/table?fromstatweb

Torta, E. (2014). Approaching independent living with robots. Eindhoven: Technische Universiteit Eindhoven. https://doi.org/10.6100/IR766648

Logbook

| Date | Name | Activity | Time spent (HH:MM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 03/02/20 | All | Discussing the subject | 02:30 |

| 06/02/20 | Bob | Searching articles, writing SotA, structuring wiki | 05:30 |

| 06/02/20 | Teis | Writing problem statement, introduction, and who are the users | 05:15 |

| 06/02/20 | Tom | Searching articles, writing SotA | 04:45 |

| 06/02/20 | Emile | Searching articles, writing SotA | 03:30 |

| 06/02/20 | Nynke | Searching articles for and writing problem statement, introduction, milestones, deliverables | 05:30 |

| 12/02/20 | Bob | Making agenda meeting 1 | 00:30 |

| 13/02/20 | All | Tutor meeting; group meeting where scope of project was narrowed down | 03:00 |

| 13/02/20 | Nynke & Tom | Working out of the interview | 01:00 |

| 16/02/20 | Teis | Further literature search; rewriting existing text | 02:30 |

| 17/02/20 | Nynke & Tom | Working out of the interview | 02:00 |

| 17/02/20 | Bob | Work out Users; further literature search | 02:30 |

| 19/02/20 | Teis | Making agenda meeting 2 | 00:30 |

| 28/02/20 | Teis | Rewriting text; extending SotA with Haru | 03:30 |