Autonomous Referee System: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

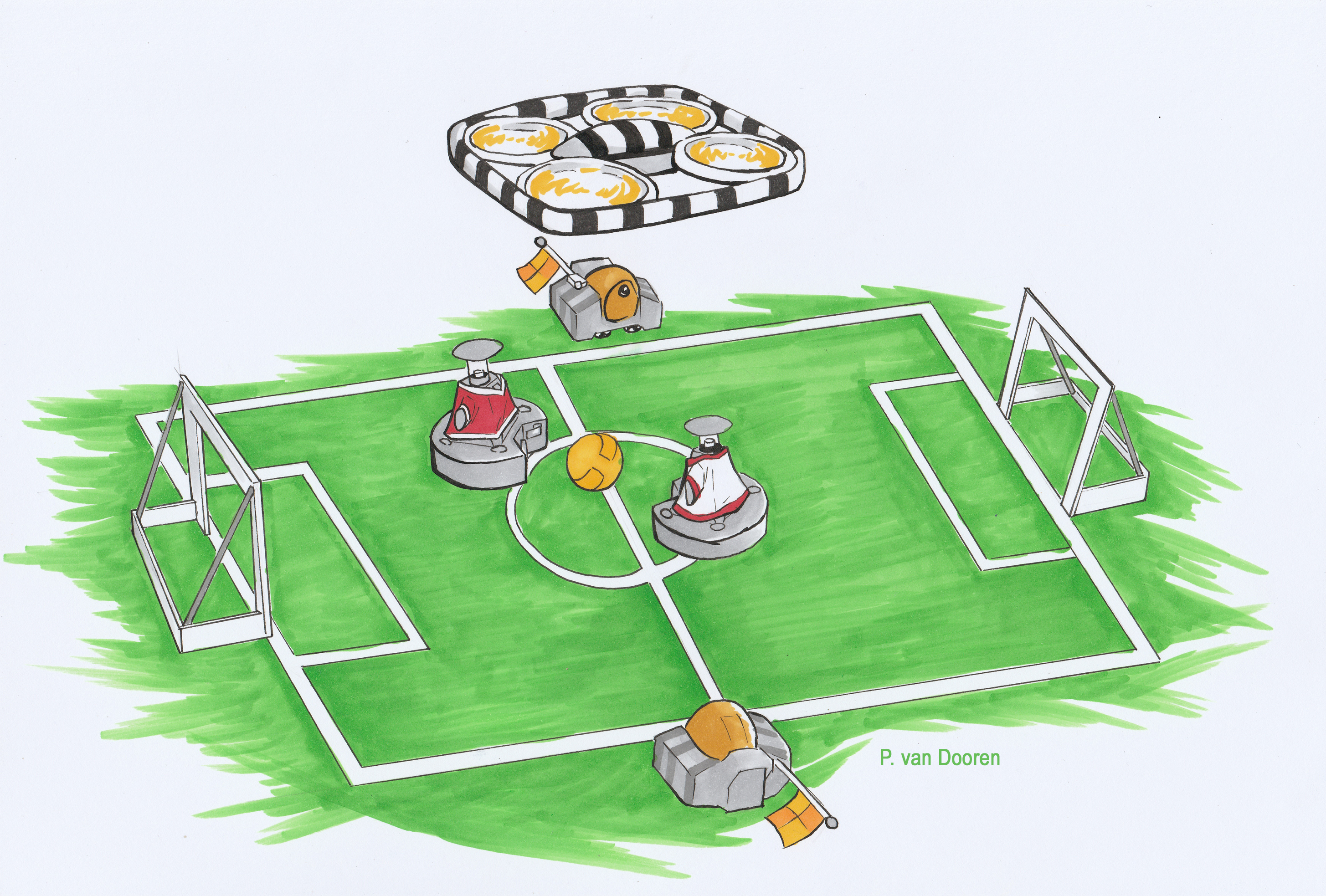

[[File:Drone Ref.png|thumb|right|600px|Illustration by Peter van Dooren, BSc student at Mechanical Engineering, TU Eindhoven, November 2016.]] | |||

<div align="left"> | <div align="left"> | ||

<font size="5">Autonomous Referee System</font><br /> | <font size="5">Autonomous Referee System</font><br /> | ||

Revision as of 21:18, 15 December 2016

Autonomous Referee System

'An objective referee for robot soccer'

Introduction

This project was carried out for the second module of the 2016 MSD PDEng program. The team consisted of the following members:

- Tim Verdonschot

- Tuncay Uğurlu Ölçer

- Sa Wang

- Joep Wolken

- Farzad Mobini

- Jordy Senden

- Akarsh Sinha

Project Definition

As described in [1] verbatim, the goal of the present project is to contribute to this vision and create an autonomous robot referee system using drones. The first generation of MSD PDEng students created a system architecture [2] to be used with a single drone. This architecture provides the basis for the present project. In particular some of the modules of such architecture, such as ball out of bound detection and an indoor positioning system using ultra-wind band technology, were implemented and tested. The overall goal of this project is to extend this system architecture and implement more modules.

Background

RoboCup is an international initiative to promote and advance research in robotics and artificial intelligence. Founded in 1997, its main goal is to ‘develop a team of fully autonomous humanoid robot soccer players which is able to win against the winner of the most recent World Cup, complying with the official rules of FIFA, by the middle of the 21st century’. In the Middle Size League (MSL), two teams of five autonomous robots play a soccer match on an artificial field. These robots are able to drive around while using several on-board camera's to position themselves on the field. Moreover, they can determine the position of the ball, opponents and team mates. Through radio signals they can communicate with each other and decide upon a strategy. With a ball-handling system the ball can be captured and controlled and a shooting mechanism is able to shoot a ball over the ground or through the air.

As discussed in Tutorial: Requirements for RoboCup MSL a standard RoboCup field measures 12x18 meters. During a match, there are ten robots on this field, driving around with velocities up to 5 m/s and possibly even higher. These robots are all competing for the same thing: scoring goals. This means that getting possession of the ball is a primary goal. When several robots are competing for the ball, collisions, pushing and scrummages are nearly inevitable. To make sure the match is played in a fair way, a human referee keeps a keen eye on the events on the field from the sideline. This human referee is backed up by an auxiliary referee which is standing on the opposite side, next to the field. Both can decide on stopping the game, due to a committed foul, a scored goal, a ball out of bound or any other event. The rules for MSL are based on the official FIFA rules, but adapted to robot football rules were necessary rulebook 2016. However, the large set of rules and the interpretation thereof can often lead to situations where a referee might decide to continue the game, while another might decide to interrupt. This can and will often lead to frustrations in the aggrieved team. Moreover, a decision made by a referee can affect the outcome of a game and even an entire championship. An example of this is the final match of the world championship 2016 in Leipzig Germany (full match, highlights). The final was played between team TechUnited from the Netherlands and team WATER from China. The winner of this would become world champion robot soccer in the MSL. At the end of the match the scoreboard showed 2-2. As in human soccer, this means extra time to decide on the winner. During the match, team WATER had some trouble with the ball handling, preventing the ball to rotate in a ‘natural’ way over the field. When it happens that the ball does not rotate in the direction it is being moved, this is considered clamping and regarded as a foul in favor of the other team. In the last couple of minutes the score was 3-3 when WATER turned towards the TechUnited goal, shot and scored the winning goal. While the Chinese team was already celebrating their victory, the auxiliary referee decided that the scoring robot was clamping the ball before scoring the goal. After a discussion with the main referee, it was decided to declare the goal invalid. Since the extra time also ended in a draw, penalties were needed to decide who would become the new world champion. After all penalties of the Chinese team were stopped by the Dutch keeper, the first shot of the TechUnited robot went into the net. The Dutch team won the penalty series with 1-0 and thus TechUnited became the world champion of 2016. This example shows how important the decisions of the human referee team can be in shaping the course of a match or even a tournament. Rules are always prone to interpretation and a team which is disadvantaged by this will always complain. The referee has no means to justify his decision other than his own intuition and interpretation on the rules. This lead to the question on whether it would be possible to develop a system which can support the human referee team in making decisions. Such system might even become fully autonomous and could replace the human factor in refereeing entirely.

Project Objectives

- System architecture of the proposed solution by January 31st along with a time plan, risk assessment of the choices, and task distribution for the elements of the group.

- Software of the proposed solutions including:

- Out of bound ball detection by the ground robot, including both motion algorithm and camera processing. Suggested: end of January.

- Detection of a fault including both movement. Suggested: end of February.

- Software with the interaction between the two robots. Suggested: end of March.

- Demo to be scheduled by the end of March or beginning of April.

- A Wiki-page documenting the project and providing a repository for the software developed, similar to the one obtained from the first generation of MSD students.

- One minute long video to be used in presentations illustrating the work.

Literature survey and background work

Definition of fault/foul

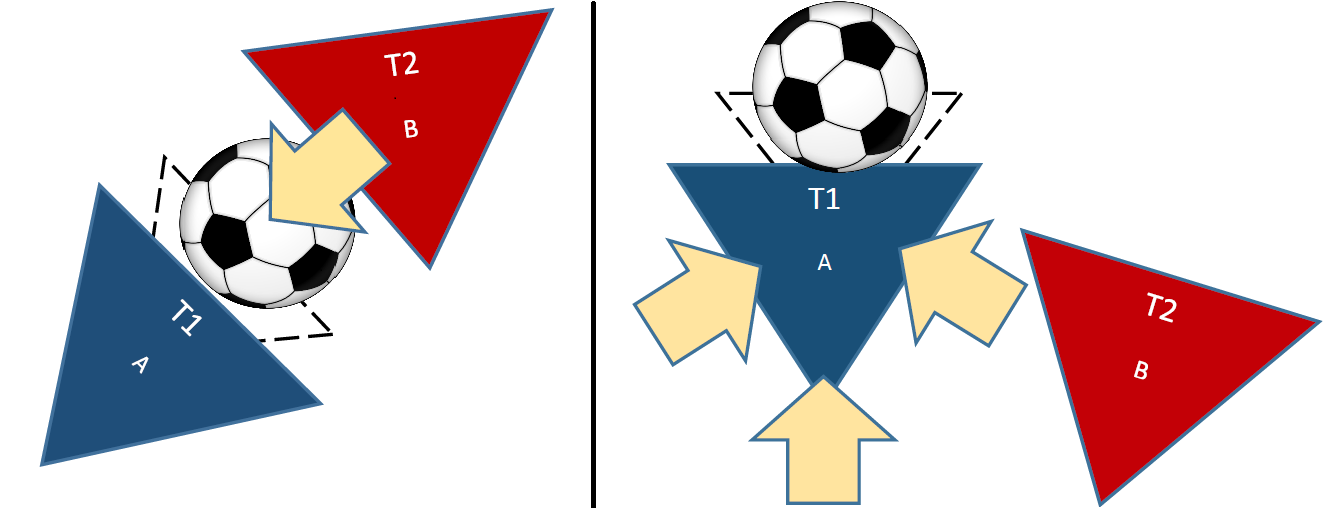

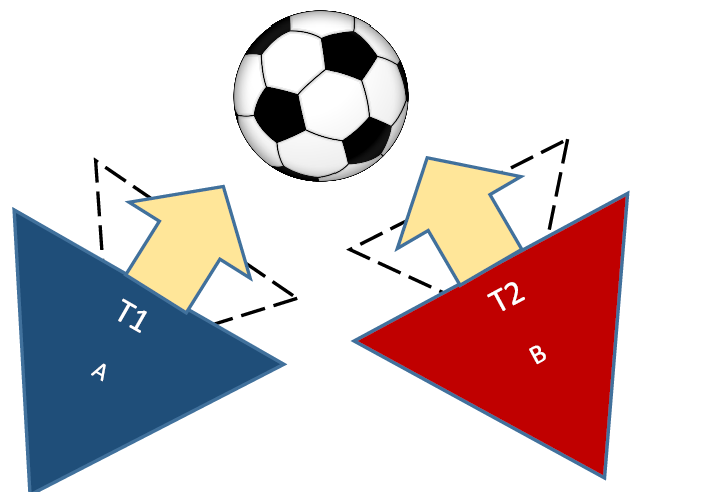

The definition of foul/fault or offence is based on the Robo Cup MSL Rule Book [3] . Simple physical contact does not represent an offence. Speed and impact of physical contact shall be used to define offence or a foul. There are two cases in which foul detection should be formulated.

- Case 1: One of the robots is in possession of the ball

- A foul will be defined in this case if Robot B impedes the progress of the opponent by

- Colliding after charging at A with v unit velocity

- Applying (instantaneous) pushing with ≥ 𝑭 unit force

- Continuing to push for time ≥ t seconds

- Knocking the ball off A by sudden (Instantaneous) application of force (≥ 𝑭 unit force)

- A foul will be defined in this case if Robot B impedes the progress of the opponent by

- Possible ways of measuring these

- Velocity

- Visual odometry (Image-based Object Velocity Estimation)

- Application of (instantaneous) force

- Use visual odometry and calculate velocity/ acceleration and include time data.

- Estimate force accordingly

- Continuous push (B is pushing A)

- Detect instantaneous application of F unit force

- Detect if B changes direction of movement within t seconds

- Knocking off ball (only visual data)

- Detect collision

- Detect ball and Player A after collision

- Case 2: None of the robots are in possession of the ball

- A foul will be defined in this case if Robot either A or B impedes the progress of the opponent by

- Colliding with larger momentum (say, pB ≥ pA units)

- Continues with the momentum the for time ≥ t seconds (dp/dt=0,for t seconds after impact)

- Possible ways of measuring these

- Momentum

- Use visual odometry to estimate velocity (and elapsed time)

- Estimate momentum accordingly

- Continuous application of momentum

- Detect if defaulter changes direction of movement within t seconds

- Momentum

- A foul will be defined in this case if Robot either A or B impedes the progress of the opponent by

References

- ↑ D. Antunes and R. Molengraft, Drone Referee, Control Systems Technology group, Mechanical Engineering Department, TU Eindhoven, November 2016.

- ↑ "Robotic Drone Referee"

- ↑ "Middle Size Robot League Rules and Regulations"