Embedded Motion Control 2013 Group 5: Difference between revisions

| Line 254: | Line 254: | ||

'''Problem:'''<br /> | '''Problem:'''<br /> | ||

'''Solution:'''<br /> | '''Solution:'''<br /> | ||

<div style="text-align: center;"> | |||

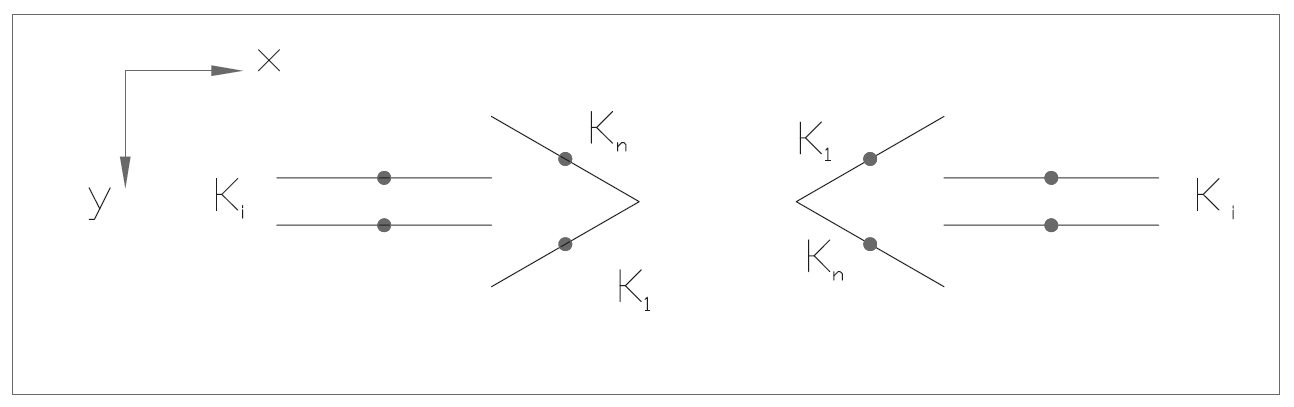

''Figure:Possible junctions'' | |||

</div> | |||

=== '''Junction node''' === | === '''Junction node''' === | ||

Revision as of 16:23, 24 October 2013

Group members

| Name: | Student ID: |

| Arjen Hamers | 0792836 |

| Erwin Hoogers | 0714950 |

| Ties Janssen | 0607344 |

| Tim Verdonschot | 0715838 |

| Rob Zwitserlood | 0654389 |

Tutor:

Sjoerd van den Dries

Planning

| DAY | TIME | PLACE | WHAT |

| Monday | 11:00 | OGO 1 | Tutor Meeting |

| Monday | 12:00 | OGO 1 | Group meeting |

| Friday | 11:00 | GEM-Z 3A08 | Testing |

| DATE | TIME | WHAT |

| September, 25th | 10:45 | Corridor competition |

| October, 23th | 10:45 | Final competition |

| October, 27th | 23:59 | Finish wiki |

| October, 27th | 23:59 | Finish peer review |

Log

Week 1:

- Installed the software

Week 2:

- Did tutorials for ROS and the Jazz simulator

- Get familiar to 'safe_drive.cpp' and use this as base for our program

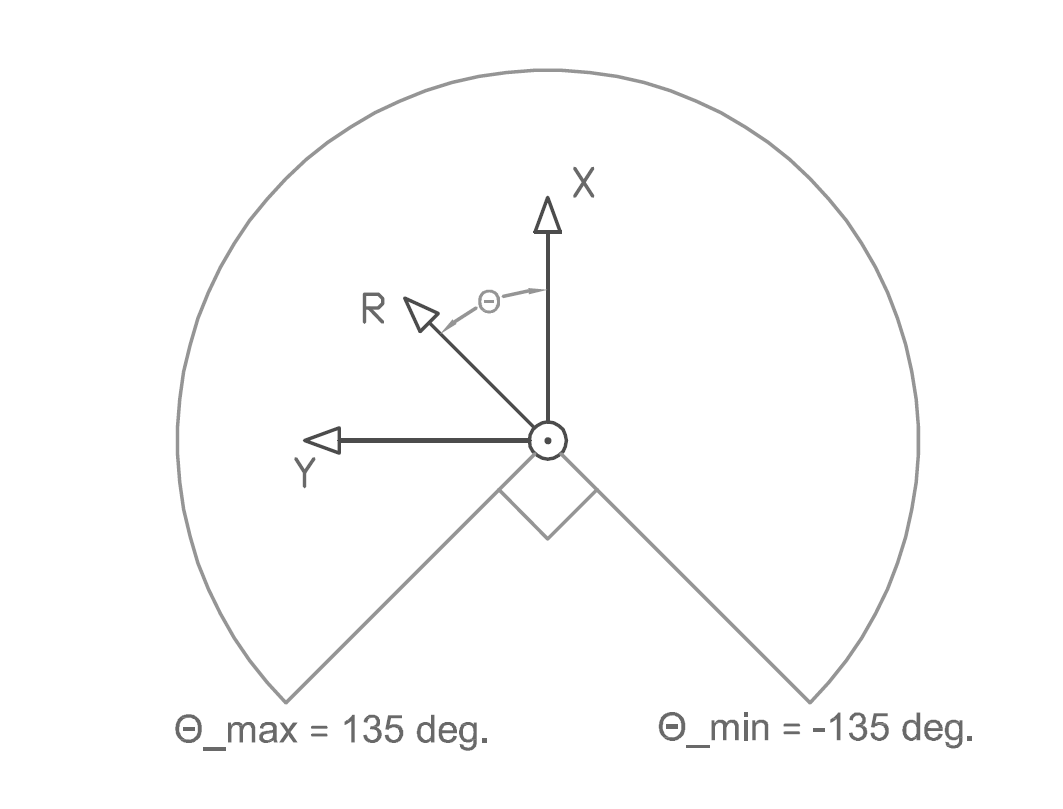

- Defined coordinate system for PICO (see Figure 1)

Week 3:

- Played with the Pico in the Jazz simulator by adding code to safe_drive.cpp

- Translated the laser data to a 2d plot

- Implemented OpenCV

- Used the Hough transform to detect lines in the laser data

- Tested the line detection method mentioned above in the simulation (see Figure 2)

- Started coding for driving straight through a corridor (drive straight node)

- Started coding for turning (turn node)

Week 4:

- Reorganize our software architecture after the corridor competition

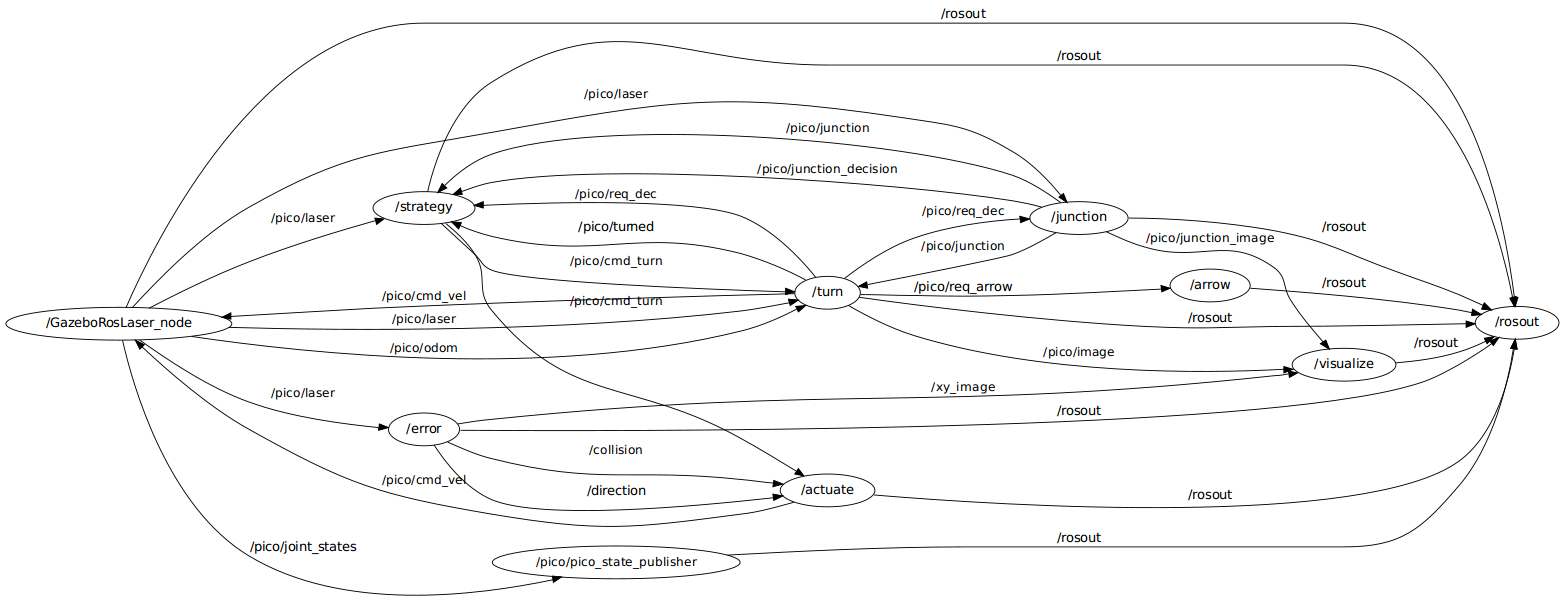

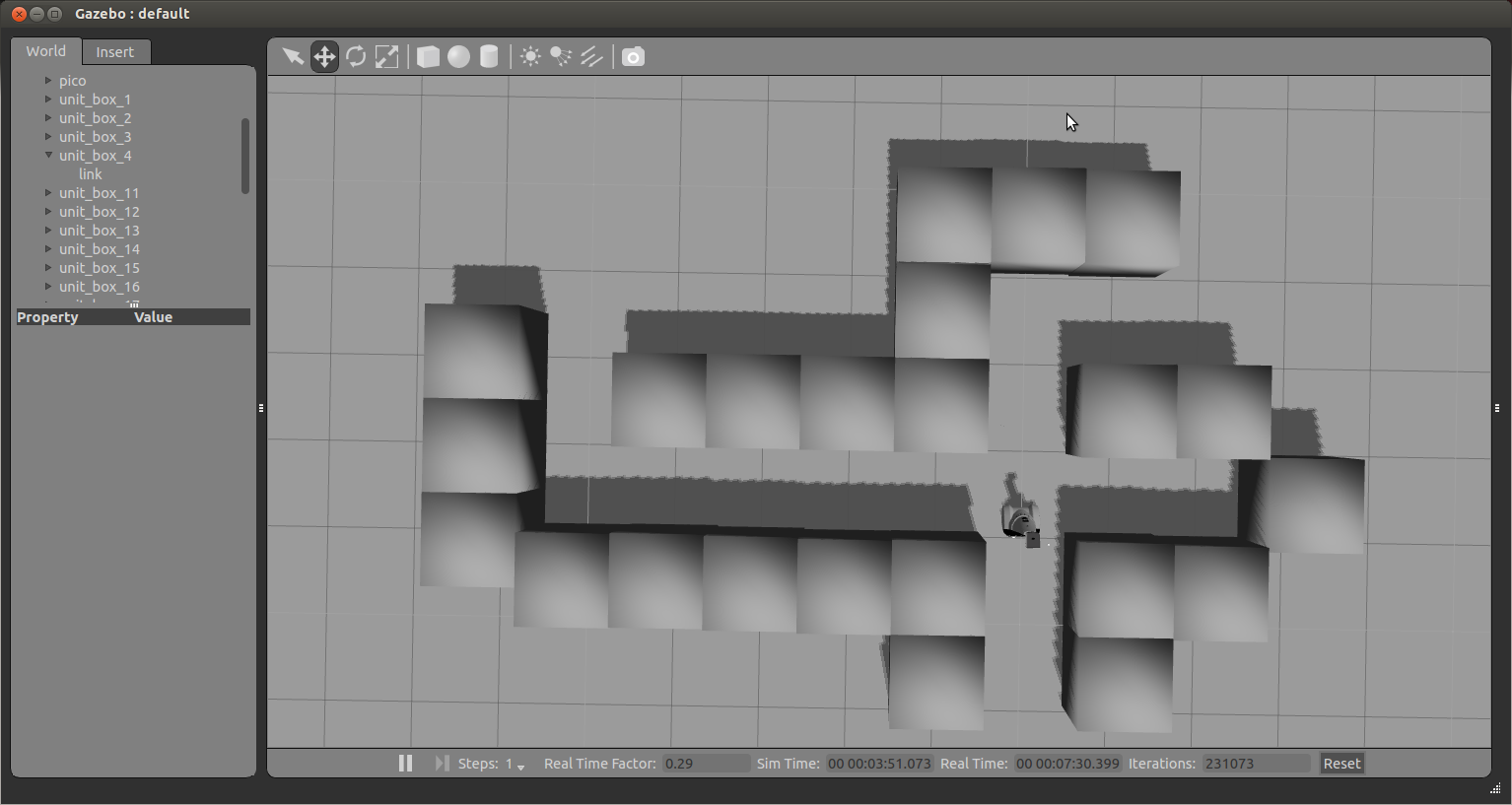

- Created structure of communicating nodes (see Figure 3)

- Finish drive straight node (see Figure 4)

- Finish turn node

- Started creating a visualization node

Week 5:

- Finish visualization node

- Started creating node that can recognize all possible junctions in the maze (junction node)

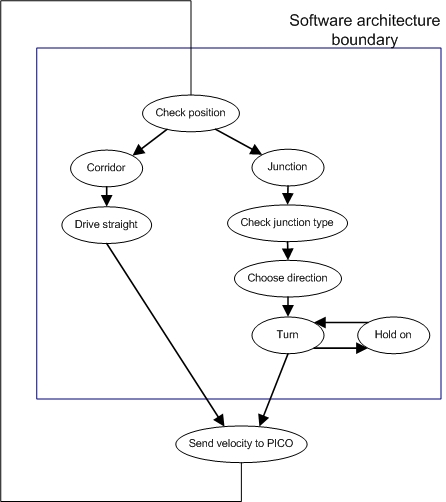

- Started creating node that generates a strategy (strategy node) (see Figure 5)

- Tested drive-straight and turn node on Pico, worked great!

Week 6:

- Finished junction node (see Figure 6)

- Started fine tuning strategy node in simulation

- Tested visualization and junction node on Pico, worked fine!

Week 7:

- Finished strategy node (in simulation)

- Tested strategy node on Pico, did not work as planned

- Did further fine tuning of strategy node

Week 8:

- Simulation ok, tested ± 30 junctions

- All nodes communicating properly w.r.t. each other

Software architecture

The software architecture is shown in figure 3. In this section the architecture is explained in more detail. First we present an overview of all nodes, inputs and outputs. Then the most challenging problems that have to be tackled to solve the maze and the solutions are discussed.

Overview nodes

The software to solve the maze is build around the strategy node. This node receives all the information that is needed to solve the maze, and sends information to the nodes that actuate Pico. An overview of all nodes is given below. The column "PROBLEMS SOLVED" give a short description of the problems that are solved in the node.

| NAME | INPUT | OUTPUT | PROBLEMS SOLVED |

| Strategy | *Laser data *Junction data *Turn data |

*Command for left, right or straight | *Finding the next best step |

| Junction | *Laser data | *Type of junction | *Junction recognition |

| Turn | *Command for left, right or straight *Laser data |

*Velocity command | *Localization *Control turning motion |

| Drive straight | *Command for left, right or straight *Laser data |

*Velocity command | *Localization *Control straight drive motion |

| Arrow detection | *Odometry data | *Command for left or right | *Arrow recognition |

The integration of the nodes can be visualized using rxgraph, which displays all used nodes and their mutual communication. This is done in figure 4.1a.

Fig 4.1a:Total software architecture

Design choices

During the entire development proces we made a number of design choices. Major decisions were made collectively. This was done by small brainstorm sessions and trial-and-error iterations. Smaller, more detailed design choices were made mostly indivudually when defining the code and are not discussed here.

At first we all agreed on a coordinate system for pico and decided that all control should be, if possible, based on feedback. Our opinion was that feedforward (driving/turning for several seconds) is not the way to go. The coordinate system is depicted in the figure below:

Figure 4.2a: PICO coordinate system

Prior to the corridor competition we dissected the work in two parts: driving straight and turning. Together these would be able to let PICO drive through the corridor. The group was split in two to work on these seperate parts. For the straight drive part we looked at the potential field algorithm and the hough tranform and decided to implement the Hough algorithm, since it is easier to implement and the hough transform also returns physical data in terms of dimensions of its surroundings (lines), which might come in use later. As for the second part, the turning algorithm, we used the derivative of the laserscan data to find peaks and thus identify corners. Once a exit was detected, we continued driving until the distance between the found corners was nearly equal.

After the corridor competition all code was still in a single file, and since we had to expand it with more algorithms we decided to re-organize the structure by creating seperate nodes and agreed on a strict input-output for each node. These nodes are displayed in table 4.1a, but at this time there was not yet a arrow/junction detection.

Now we started on a new turning and driving straight algorithm, because the first one did not work well enough. For the turning we have come op with a homebrew solutionn (XXX verwijzing naar) instead of turning for a given time (no feedback) or using odometry (false feedback). For the straight driving we use the hough from the openCV functions & libraries.

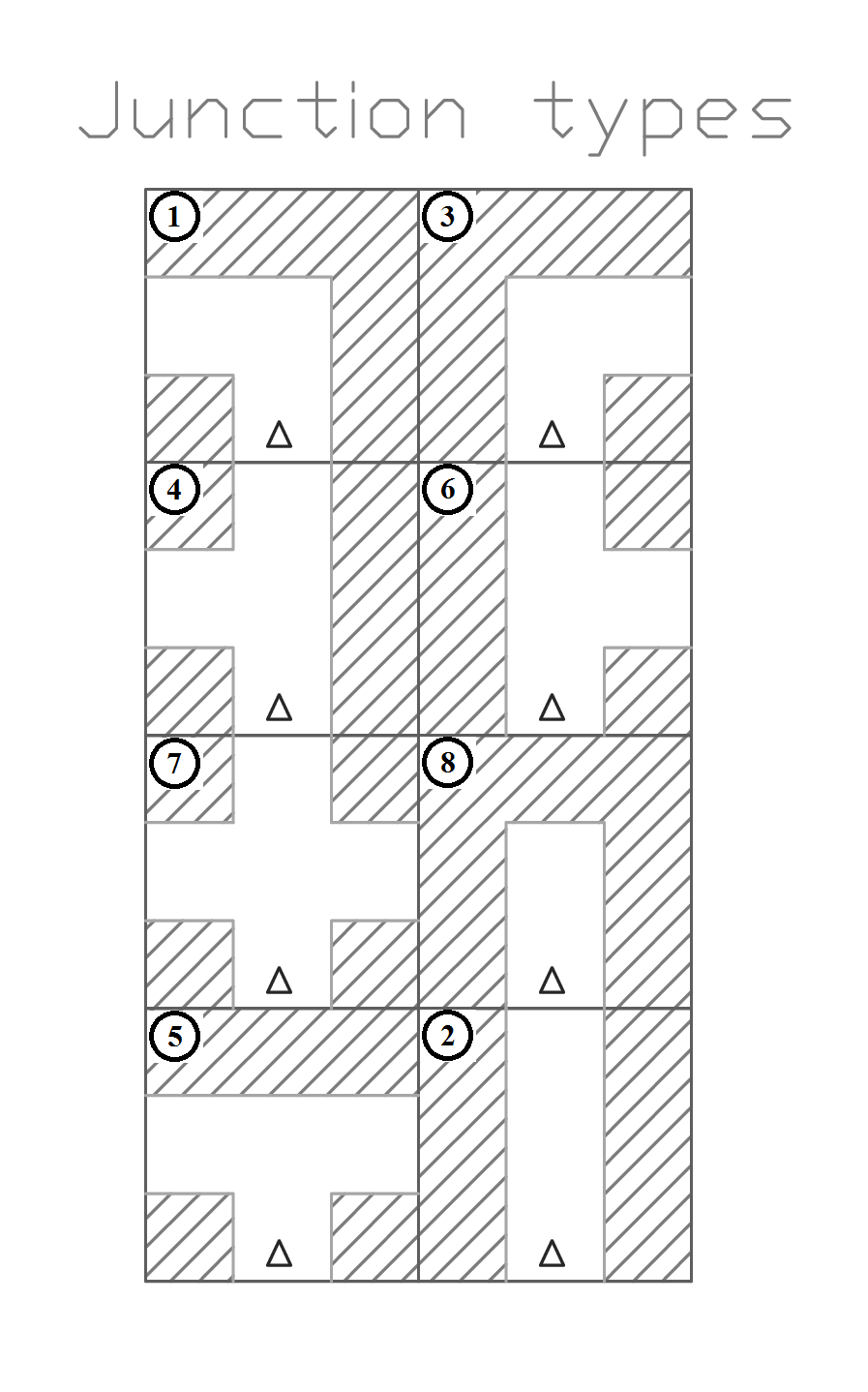

When these functions were completed we started to expand the software with extra nodes, Strategy, Junction and Arrow detection. To do this we first collectively discussed the approach for these nodes and determined the possible junctions PICO could encounter. As the deadline (maze competition) was coming closer we decided to first build a wall follower and then add extra options to this to make PICO smarter. So the plan was to first build a wall follower which can recognize dead ends and avoid these (which we call wall follower++), and if there was any spare time we could implement a mapping algorithm.

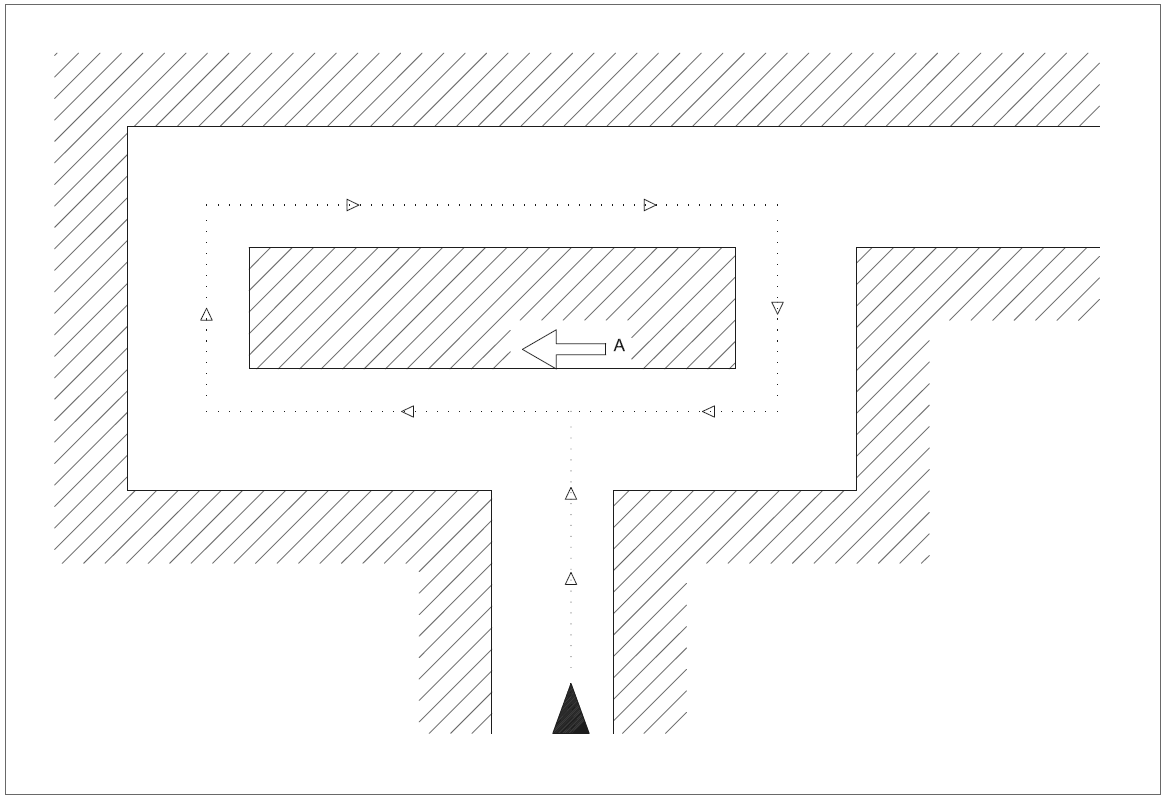

For the arrow detection we chose for a gradient based search algorithm. At first we had another one (based on outer positions of points on the arrow) but this was not usable when the arrow was tilted. The gradient based algorithm is more robust, so we used that one. We decided not to use the outcome of the arrow node in the strategy node since it may cause problems. This problem can best be recognized when visualized:

Figure 4.2b: infinite tracjectory

When we would use a (semi) wall following algorithm but also implement the arrow detection in the strategy the result may be an infinite loop. This occurs when there are multiple paths that lead towards the exit. For example in the figure, if we prefer PICO to make right turns but take a single left (as suggested by the red arrow A), PICO will continue to go right after this left turn and as a result, be stuck on this "island" in the maze. For other directions an anologous situation can be depicted.

Strategy

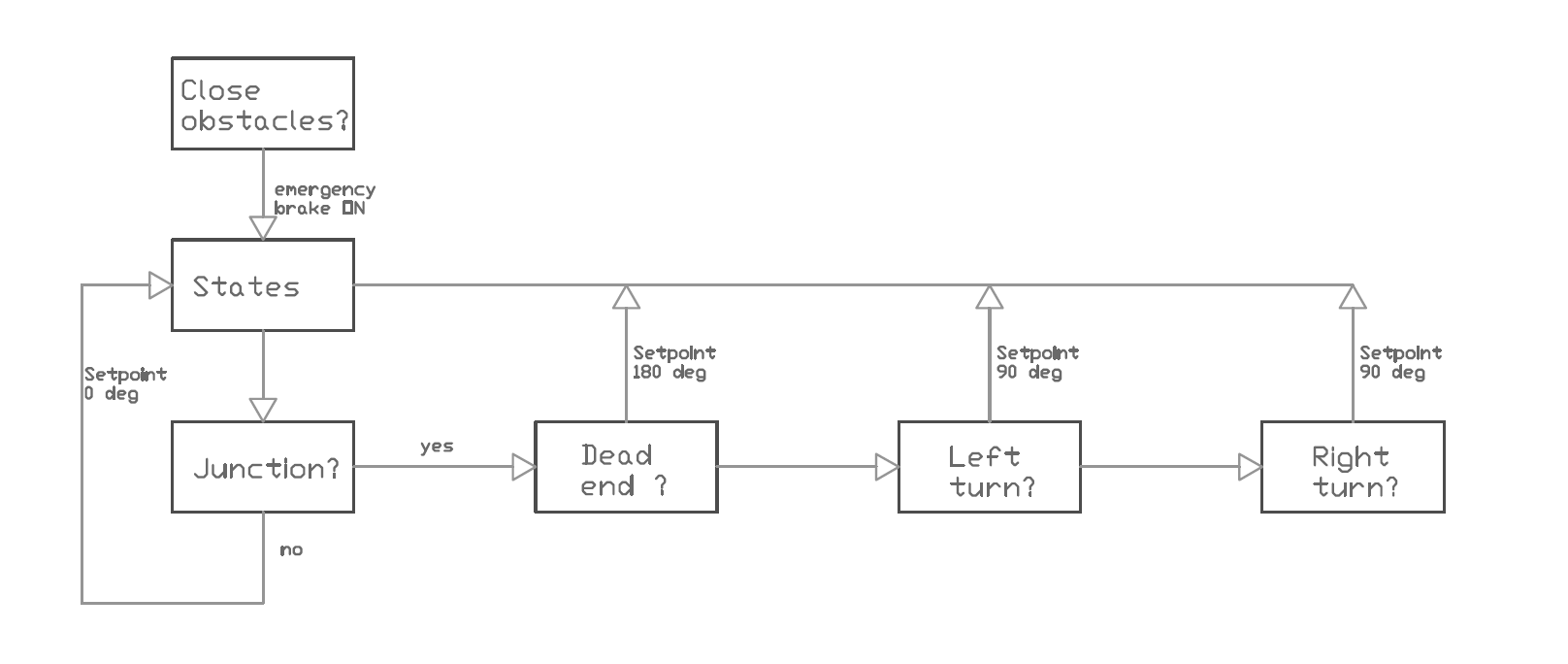

The goal of this competition is to solve the maze. The strategy node contains the plan of action to achieve this goal. The name of the strategy that is used is: Wall follower ++. This is basically a wall follower to the left but with the extension of dead end check. This will be explained in more detail later on. Figure 4.3a is a schematic representation of the strategy that is used. It is an ongoing loop which gets all the input data at the beginning of one cycle and ends the cycle with sending a command of what Pico should do. There is one exception in this ongoing loop, and that is when Pico is turning. More information about this exception is given later. Next the scheme in figure 4.3a is discussed.

Fig 4.3a: High level software architecture

It all starts with a position check, the node will determine whether Pico is in a corridor or at a junction. When Pico is in a corridor it will send a command to drive straight trough the corridor. The straight-drive node react on this command a will control the motion of Pico. When Pico is at a junction, the strategy node will first check what type of junction it is. This information is given by the junction node. When the junction type is clear, the strategy node will make a decision based on the scheme in figure 4.3b, this is a scheme of a standard wall follower. But as mentioned above it is extended with a dead end detector.

Figure 4.3b: Strategy, steps for driving

This means that when Pico has the possibility to go left, it will first be checked whether the corridor on the left is a dead end or not. When it is, the option to go left will not be take into account. So when Pico is at a junction it actually checks if there is a new junction after the current junction. Basically the strategy node is able to look two junctions ahead and makes a decision based on that information. When the decision is made, the strategy node will send a command to the turn node which controls the turn motion. This is the point when the ongoing loop holds for a while. The turn node will make shore that Pico turns the way the strategy node has commanded and will give a command back when the turn is completed. After that command the strategy node will continue the loop. So what the strategy node does is collect all input signals, decides what would be the best step to take to solve the maze and commands either to the straight-drive or turn node to control the motion. The special feature of the Wall follower ++ strategy is that it makes a decision based on the information that is gathered by looking two junctions ahead.

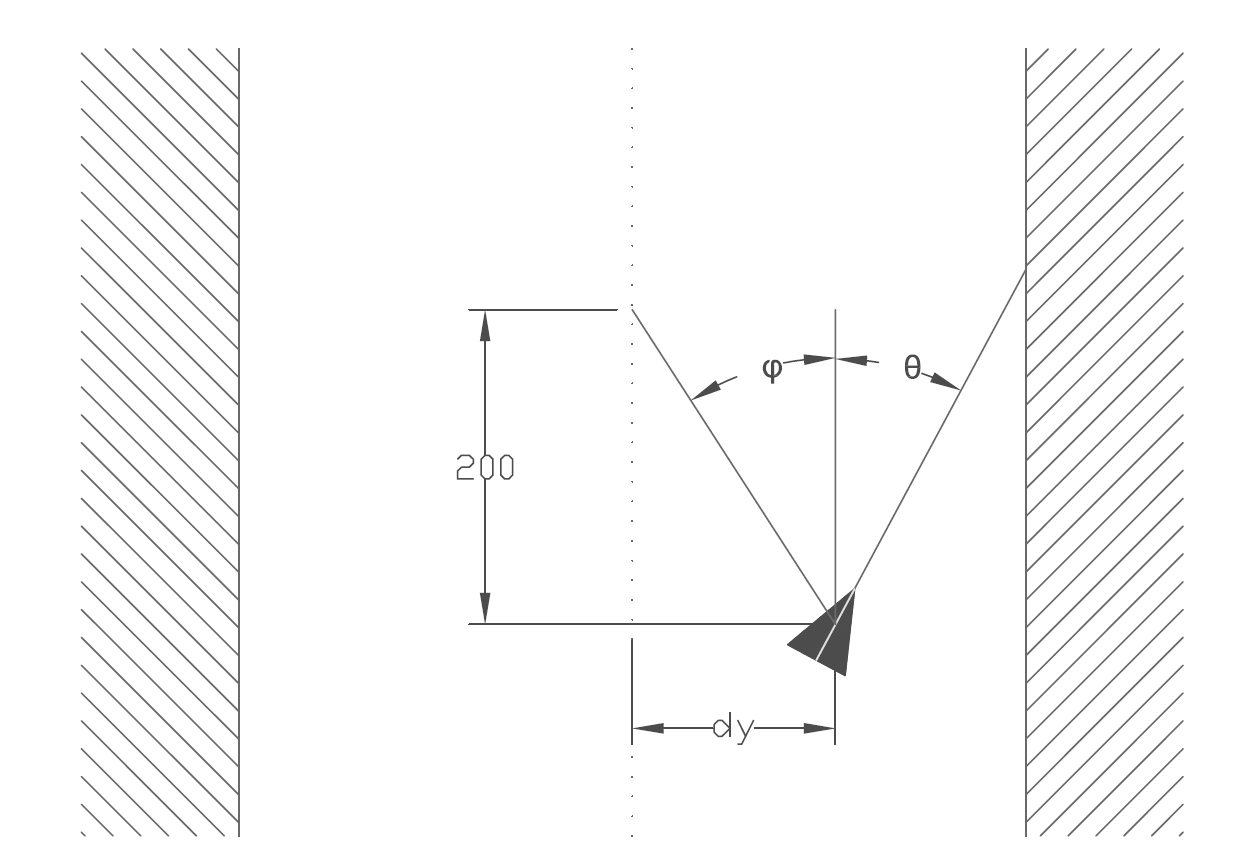

Control motion: drive straight

Pico is driving through a rather narrow corridor and may not hit the wall. So when Pico is between two walls (this is determined in our turn and strategy node) the “drive straight†node is activated until pico is on a junction again. This node lets pico drive parallel to the wall and in the middle of the corridor. This is done by the following algorithm/pseudo code.

1. Create black-white image from the laserdata.

- The laserpoints will be white the rest black.

- Pay attention to the orientation of the picture.

2. Find lines through opencv function HoughlinesP()

- These will correspond to the walls.

- Returns (x,y) coordinates of begin and endpoints of the lines.

- Coordinate system in top left corner, positive x axis to the right, positive y down.

3. Calculate angle of the lines 'theta' , and length 'd' of a vector perpendicular to the line. See figure (..)

- Express these in the 'pico' coordinate system.

4. Pick the closest wall

- Based on the smallest 'd'.

5. Find the opposite wall

- Using 'theta' of the closest wall, the index in the laserdata of the closest point is calculated.

- Since the walls should be about parralel the same theta is used to find the index of the opposite wall.

6. Find middle of the corridor 7. Calculate drive angle

- Using the distance to the middle and a arbitrary distance along the corridor we find 'phi'.

- Our drive angle will be 'theta', to get parallel to the wall, plus 'phi' to turn towards the setpoint in the middle of the corridor.

8. Send the drive angle.

- the drive angle is set to a node called actuate. This node sets an x speed and uses the drive angle as the z-rotation speed.

As discussed above, the setpoint generator can be visualized as following:

Figure:Setpoint generation

Turn node

Problem:

Solution:

Figure:Possible junctions

Junction node

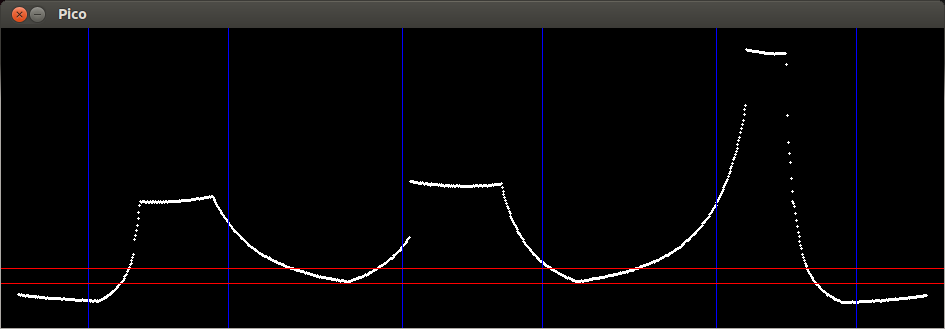

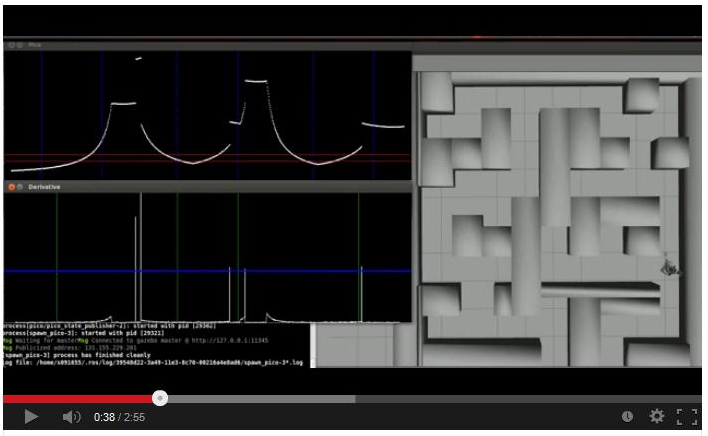

Before we transform the LRF data using the Hough function, we check at which type of surroundings we are dealing with. There are a number of possibilities, which are displayed in figure 8.

Using the laser range data, we can distinguish these situations by analyzing their values. Each situation has an unique amplitude-angle characteristic. We can generalize variations on the situations by assuming that a junction exit will reach a scanning range value above r_max. Setting the limit at r_max and thus truncating the scanning values will return characteristic images for each junction type:

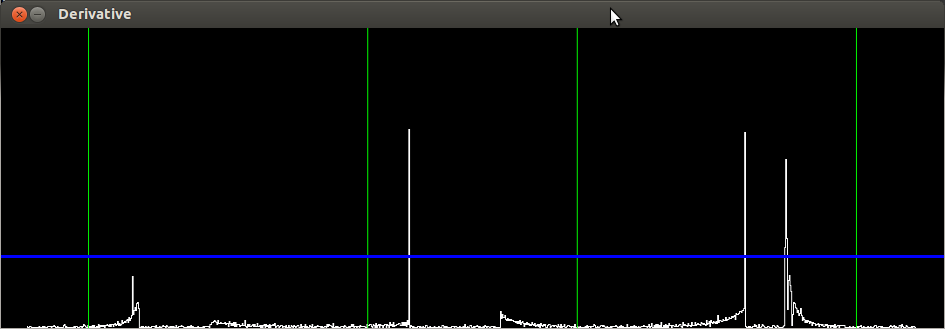

Fig: Truncated LRF data (horizontal axis: scan angle, vertical axis: scan range)

If the average value (angle) of the truncated tops reach setpoint values (i.e. 0, 90, 180 degrees) w.r.t. the y axis we know what kind of junction we are dealing with. Now that we can identify the type of surroundings, we can tell if we have to navigate in a straight manner (corridor) or if we need to navigate towards an exit. With this information we can send messages to our motion node. So if we look at the figure above, we can identify three seperate exits.

The possible junction types are:

Fig 5:Different types of junctions

Fig

Fig

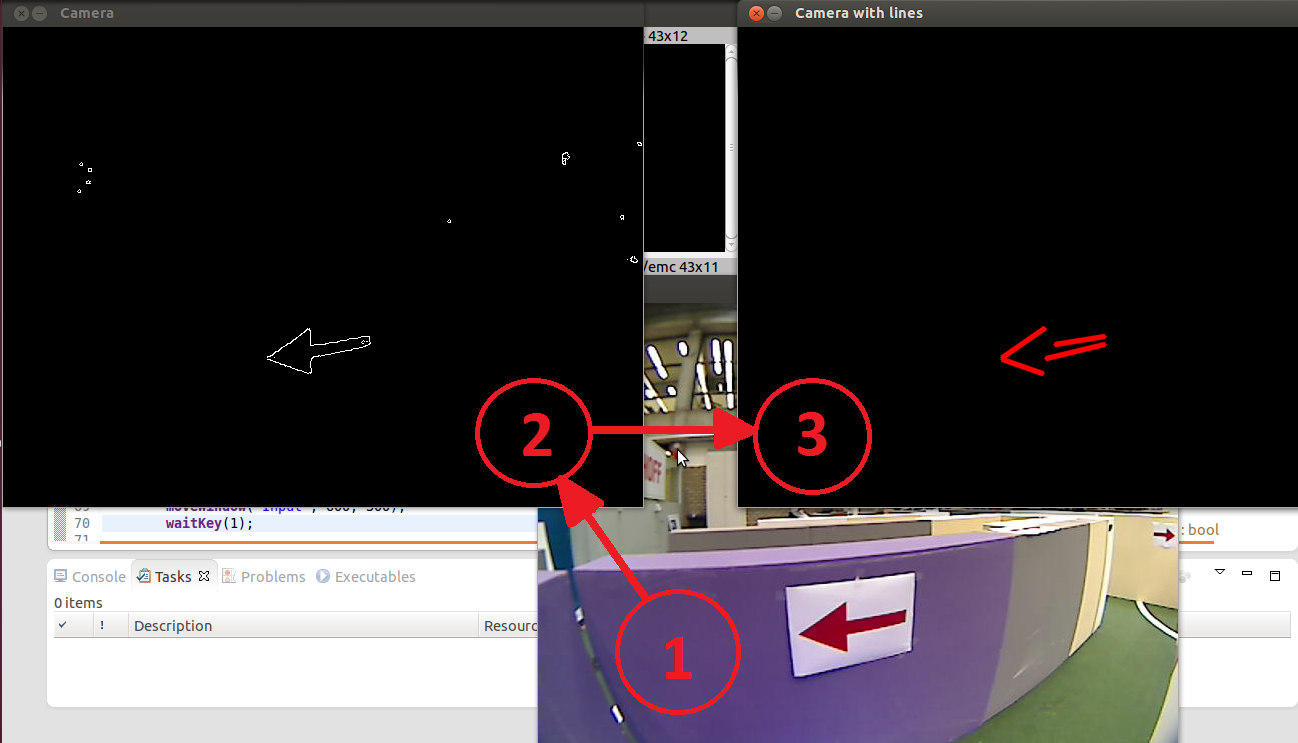

Arrow recognition node

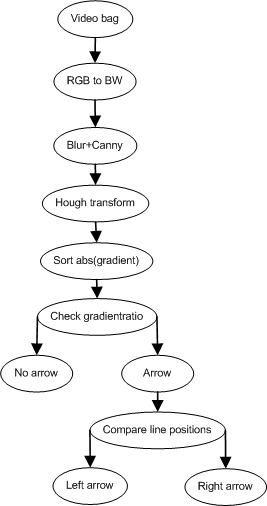

As mentioned before, we did incorporate arrow recognition in the software. We kept the results on a scrict information-output basis (using a cout//). The arrow recognition software was constructed as a seperate node which communicates with the central strategy node. The architecture of this node is displayed in the figure below in chronological order:

fig 4.7a):Pseudocode for arrow recognition

When online, these functions output their data to the GUI as displayed in figure 4.7b.

fig 4.7b):Steps involving arrow recognition

We first convert the video (bag, see step 1 of figure 4.7b) from red, green and blue (RGB) to black and white (BW). Next, we apply a blur filter to the image. This is a openCV function and smoothes the image. After this a Canny edge detector is applied. We now have the countours displayed as displayed in step 2 of figure 4.7b. Next, we apply a Hough transform to this countour. The options are tweaked such that only the arrows tail and head is found by the Hough transform. Now we have arrived at step 3 of figure 4.7b. Next, we calculate the gadient ([math]\displaystyle{ K_i=\frac{dy_i}{dx_i} }[/math], i=1..n, n=no. found lines) and average x-value (indicated by the points in figure 4.7c. We couple these values and then we sort these by the magnitude of the gradients. These variables are shown in the figure below.

Fig 4.7c):arrow properties

We want to compare the head of the arrow with its tail. If the average x position of the head is smaller than its tail we know it points to the left and vice versa to the right. We know that [math]\displaystyle{ K_1 }[/math] has the largest gradient and [math]\displaystyle{ K_n }[/math] the lowest. The tail is somewhere in between. So if we compare the average x corresponding to the maximum gradient with that of the median gradient we can find the orientation of the arrow by checking at which side (x) the maximum gradient is w.r.t. the median gradient.

Evaluation

Now PICO is equiped with arrow recognition, junction detection, dead end detection (skips dead end corridors) and a wall follower. This is displayed in the video below.

Project, encountered problems

Concluding remarks

References

- A. Alempijevic. High-speed feature extraction in sensor coordinates for laser rangefinders. In Proceedings of the 2004 Australasian Conference on Robotics and Automation, 2004.

- J. Diaz, A. Stoytchev, and R. Arkin. Exploring unknown structured environments. In Proc. of the Fourteenth International Florida Artificial Intelligence Research Society Conference (FLAIRS-2001), Florida, 2001.

- B. Giesler, R. Graf, R. Dillmann and C. F. R. Weiman (1998). Fast mapping using the log-Hough transformation. Intelligent Robots and Systems, 1998.

- Laser Based Corridor Detection for Reactive Navigation, Johan Larsson, Mathias Broxvall, Alessandro Saffiotti http://aass.oru.se/~mbl/publications/ir08.pdf