PRE2023 3 Group4: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 729: | Line 729: | ||

Although the outcomes of this study deviated from expectations, they still shed valuable light on the field of Human-Robot Interaction (HRI), which holds significant relevance in contemporary society. Future research endeaveours can build upon these findings, refining them by addressing identified limitations. Primarily, it became evident that participants didn't always interpret the narrative as intended. To solve this, preliminary testing of the story and robot's emotional cues on non-participants could refine storylines before the main study. Additionally, participants noted difficulties comprehending the stories and maintaining focus during the robot's movements. Implementing measures such as pre-reading the story or initially having the robot deliver the story without movements could remove this issue. Moreover, Pepper's chest screen could be utilized to visually complement the story, enhancing engagement. These strategies aim to increase the likelihood that the stories have the intended effect, and therefore provide more valuable insights into emotion-message congruence. | Although the outcomes of this study deviated from expectations, they still shed valuable light on the field of Human-Robot Interaction (HRI), which holds significant relevance in contemporary society. Future research endeaveours can build upon these findings, refining them by addressing identified limitations. Primarily, it became evident that participants didn't always interpret the narrative as intended. To solve this, preliminary testing of the story and robot's emotional cues on non-participants could refine storylines before the main study. Additionally, participants noted difficulties comprehending the stories and maintaining focus during the robot's movements. Implementing measures such as pre-reading the story or initially having the robot deliver the story without movements could remove this issue. Moreover, Pepper's chest screen could be utilized to visually complement the story, enhancing engagement. These strategies aim to increase the likelihood that the stories have the intended effect, and therefore provide more valuable insights into emotion-message congruence. | ||

One of the limitations that was mentioned was the choice for pre-installed | One of the limitations that was mentioned was the choice for pre-installed Choregraphe behaviours. This lead to led to less the emotions being perceived as too exaggerated by many participants. In future research, it is recommended to spend to more time getting familiar with suitable programs and methods for programming Pepper. This could lead to more nuanced and subtle expressions that would be more appealing for the listeners. For this, also more research would have to be done into perceiving in human-robot interaction with Pepper, paying attention to what cues humans use to pick up on certain emotions of robots. Furthermore, by manually programming Pepper, more variation can be introduced in the intensities of the emotions during the story-telling, meaning the gestures and emotions as shown by Pepper correspond better to the context of the story that is told. Besides, a wider range of emotions could be used in future research, instead of only “happy”, “sad” and “neutral”, to gain more knowledge into the exact emotion that is preferred by participants, as they now often saw the “happy” and “sad” robot as too extreme. In real life, human emotions manifest across a nuanced spectrum. Emotions are very subtle and complex, since the perception of emotions is highly sensitive to context and personal factors. This implies the importance of considering this complexity in refining Pepper's emotional behavior<ref>Ben-Ze'ev, Aaron. (2001). The subtlety of emotions. Psycoloquy. 12. </ref>. | ||

In future investigations, it would be compelling to conduct a study with a more extensive participant pool. As depicted in Table 7, 8 and 9, while many participants exhibited consistent preferences for specific robots, outliers were observed — individuals with differing perceptions or opinions on robot emotions. Replicating the experiment on a broader scale as confirmatory research, with appropriate improvements, allows for statistical significance testing and could enhance the generalizability of results. Only then it is possible to validate whether the observed patterns hold true for a larger demographic. | In future investigations, it would be compelling to conduct a study with a more extensive participant pool. As depicted in Table 7, 8 and 9, while many participants exhibited consistent preferences for specific robots, outliers were observed — individuals with differing perceptions or opinions on robot emotions. Replicating the experiment on a broader scale as confirmatory research, with appropriate improvements, allows for statistical significance testing and could enhance the generalizability of results. Only then it is possible to validate whether the observed patterns hold true for a larger demographic. | ||

Latest revision as of 13:10, 4 April 2024

Group members

This study was approved by the ERB on Sunday 03/03/2024 (number ERB2024IEIS22). For this approval, an ERB form was filled in and a research proposal was made.

| Name | Student Number | Current Study program | Role or responsibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Margit de Ruiter | 1627805 | BPT | Note-taker |

| Danique Klomp | 1575740 | BPT | Contact person |

| Emma Pagen | 1889907 | BAP | End responsible Wiki update |

| Liandra Disse | 1529641 | BPT | Planner |

| Isha Rakhan | 1653997 | BPT | Programming responsible |

Introduction

The use of social robots, specifically designed for interacting with humans and other robots, has been rising for the past several years. These types of robots differ from the robots we have been getting used to over the past decades which often only perform on specific and dedicated tasks. Social robots are now mostly used in services settings, as companions and support tools [1][2]. In many promising sectors of application, such as healthcare and education, social robots must be able to communicate with people in ways that are natural and easily understood. To make this human-robot interaction (HRI) feel natural and enjoyable for humans, robots must make use of human social norms[3]. This requirement originates from humans anthropomorphizing robots, meaning that we attribute human characteristics to robots and engage and form relationships with them as if they are human[4][3]. We use this to make the robot’s behavior familiar, understandable and predictable to us, and infer the robot’s mental state. However, for this to be a correct as well as intuitive inference, the robot’s behavior must be aligned with our social expectations and interpretations for mental states[4].

One very important integrated element in human communication is the use of nonverbal expressions of emotions, such as facial expressions, gaze, body posture, gestures, and actions[3][4]. In human-to-human interaction as well as human-robot interaction, these nonverbal cues support and add meaning to verbal communication, and expressions of emotions specifically help build deeper and more meaningful relations, facilitate engagement and co-create experiences[5]. Besides adding conversational content, it is also shown that humans can unconsciously mimic the emotional expression of the conversational partner, known as emotional contagion, which helps to emphasize with others by simulating their feelings[3][5]. Due to our tendency to anthropomorphize robots, it is possible that emotional contagion also occurs during HRI and can facilitate making users feel positive affect while interacting with a social robot[5]. Artificial emotions can be used in social robots to facilitate believable HRI, but also provide feedback to the user about the robot’s internal state, goals and intentions[6]. Moreover, they can act as a control system through which we learn what drives the robots’ behavior and how it is affected by and adapts due to different factors over time[6]. Finally, the ability of social robots to display emotions is crucial in forming long-term social relationships, which is what people will naturally seek due to the anthropomorphic nature of social robots[3].

Altogether, the important role of emotions in human-robot interaction requires us to gather information about how robots can and should display emotions for them to be naturally recognized as the intended emotion by humans. A robot can display emotions when it combines body posture, motion velocity, facial expressions and vocal signs (e.g. prosody, pitch, loudness), highly depending on the possibilities considering the robot’s morphology and degree of anthropomorphism[7][8][9] Social robots are often more humanoid, increasing anthropomorphism, and therefore a match is required between the robot's behavior and appearance to avoid falling into the uncanny valley, which elicits a feeling of uneasiness or disturbance[7][10]. Some research has already been done on testing the capability of certain social robots, including Pepper, Nao and Misty, to display emotions and resulted in robot-specific guidelines on how to program displaying certain emotions[11][12][13].

Based on these established guidelines for displaying emotions, we can look further into how humans are affected by the robot’s emotional cues during interaction with a robot. We will research this in a context where we would also expect a human to display emotions, namely during telling an emotional story. Our research takes inspiration from the study of Van Otterdijk et al. (2021)[14] and Bishop et al. (2019)[11] in which the robot Pepper was used to deliver either a positive or negative message accompanied by congruent or incongruent emotional behavior. We extend on these studies by taking a different combination of context for application and research method: interaction with students as researching application in an educational setting rather than healthcare and using interviews to gain a deep understanding rather than surveys. We opted for this qualitative approach, as we had to work with a small participant pool of ten people due to feasibility constraints. This allowed us to dig deeper into the details of robot-human interaction by capturing the intricate nuances of participants’ experiences and perspectives, providing us with a deeper understanding of our topic. Moreover, students are an important target group for robots, because they represent future workforce and innovations. Understanding their needs can help developers design the robots so that they are engaging, user-friendly and educational[15].

More specifically, the research question that will be studied in this paper is “To what extent does a match between the displayed emotion of a social robot and the content of the robot’s spoken message influence the acceptance of this robot?”. We expect that participants will prefer interacting with the robot while displaying the emotion that fits with the content of its message and to be open to more future interactions like this with the robot. On the other hand, we expect that a mismatch between the emotion displayed by robot and the story it is telling will make participants feel less comfortable and therefore less accepting of the robot. Moreover, we expect that the influence of congruent emotion displaying will be more prominent with a negative than a positive message. The main focus of this research is thus on how accepting the students are of the robot after interacting with it, but also gaining insights into potential underlying reasons, such as the amount of trust the students have in the robot and how comfortable they feel when interacting with them. The results could be used to provide insights into the importance of congruent emotion displaying and whether robots could be used on university campuses as assistant robots.

Method

Design

This research consisted of an exploratory study. The experiment was a within-subjects design, where all the participants were exposed to the six conditions of the experiment. It consisted of a 2 (positive/negative story) x 3 (happy/neutral/sad emotion displayed by robot) experiment. These six conditions differ in terms of a match between the content of the story (either positive or negative) and the emotion (happy, neutral or sad) of the robot. An overview of the conditions can be seen in Table 1.

| Story / displayed emotion | Happy | Neutral | Sad |

| Positive | Congruent | Emotionless | Incongruent |

| Negative | Incongruent | Emotionless | Congruent |

The independent variables in this experiment were the combination of displayed emotion and the kind of emotional story. The dependent variable was the acceptance of the robot. This was measured by qualitatively analyzing the interviews held with the participants during the experiment.

Participants

The study investigated the viewpoint of students and therefore the participants were gathered from the TU/e. We have chosen to target this specific group because of their in general higher openness to social robots and the increased likelihood that this group will deal a lot with social robots in the near future[15].

Ten participants took part in this experiment and all the participants were allocated to all the six conditions of the study. There were five men and five women who completed the study. Their age ranged between 19 and 26 years, with an average of 21.4 years (+- 1.96). They are all students at the Eindhoven University of Technology and volunteers, meaning they were not compensated financially for participating in this study. The participants were gathered from the researchers’ own networks, but multiple different studies were included (see Table 2). The general attitude towards robots of all the participants was measured, and all of them had relatively positive attitudes towards robots. Most of the participants saw robots as a useful tool that would help to reduce the workload of humans, however two participants commented that current robots would be unable to fully replace humans in their jobs. When asked whether they had been in contact with a robot before, six of the participants had seen or worked with a robot before. One participant was even familiar with the Pepper robot that was used during the experiment. Three participants responded that they had not been in contact before, but they had experience with AI or Large Language Models (LLM). One participant had never been in contact with a robot before but did not comment on whether they had used AI or LLM. All in all, the participants were all familiar with robots and the technology surrounding robots, which is expected as robots in general are a large part of the curriculum of the Technical University they are enrolled at.

| Study | Number of participants |

| Psychology and Technology | 3 |

| Electrical engineering | 2 |

| Mechanical engineering | 1 |

| Industrial Design | 1 |

| Biomedical technology | 1 |

| Applied physics | 1 |

| Applied mathematics | 1 |

Materials

Robot Pepper

For this experiment, the robot Pepper was used, which is manufactured by SoftBank Robotics.

The reason this robot was chosen is because Pepper is a well-known robot that multiple studies have been done on and that is already being applied in different settings, such as hospitals and customer service. Based on young adults' preferences for robot design, Pepper would also be most useful in student settings, given its human-like shape and ability to engage emotionally with people[16]. The experiment itself was conducted in one of the robotics labs on the TU/e campus, where the robot Pepper is readily available.

When looking for a suitable robot for our project, the robots that were readily available at the TU/e and suggested by the supervisors of this research were considered, including Misty, SociBot and Pepper. With those robots in mind, the possibilities for conveying the desired emotions were compared. According to Cui et al. (2020)[17], posture is considered important for conveying emotions, and out of the three options, Pepper was the most suitable for that task. Next to that, Pepper was used in the aforementioned study by Van Otterdijk et al. (2021)[14] and Bishop et al. (2019)[11], which added to the convenience of using Pepper.

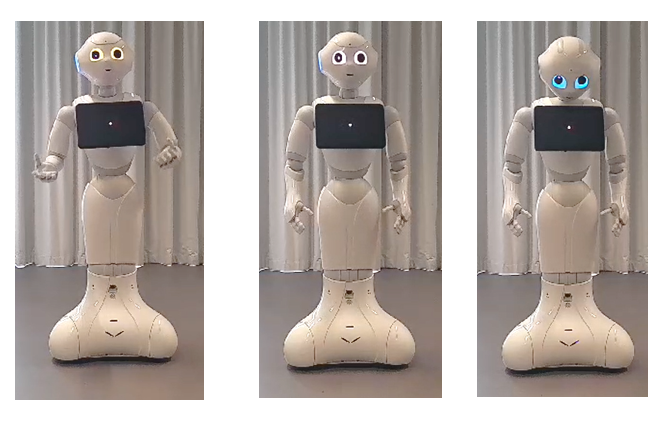

Pepper was programmed in Choregraphe to display happiness and sadness based on the voice, body posture and gestures, and LED eye colour. The behavior that Pepper displayed is shown in Table 3 and Figure 1, based on the research of Bishop et al. (2019)[11] and Van Otterdijk et al. (2021)[14]. Facial expressions cannot be used, since the morphology of Pepper does not allow for it.

| Happy | Neutral | Sad | |

| Pitch of voice | High pitch, speed, volume and emphasis | Average of happy and sad condition | Low pitch, speed, volume and less emphasis |

| Body posture and gestures | Raised chin, extreme movements, upwards arms, strong nodding | Average of happy and sad condition | Lowered chin, small movements, hanging arms, not looking around |

| LED eye colour | Yellow | White | Light blue |

The voices for each story were created using Voicebooking.com, using their free AI voice over generator. This program was chosen instead of the built-in Pepper voice because it was quite inaudible for some parts of the stories the robot was supposed to tell. In Voicebooking, the preferred voice was picked and there were moods created based on adjustments for the speed, pitch, and emphasis of the storytelling. The greatest values of each of these were assigned to the happy mood and the lowest for the sad one . For the neutral robot, the values were averaged out between these two, as mentioned in Table 3. After uploading these audio files to Choregaphe, the volume levels were changed to 80%, 90%, and 100% for the sad, neutral, and happy robot, respectively[18].

Pepper's posture and gestures were created with dialog boxes that were readily available in Choregraphe. Dialog boxes are graphical interfaces that contain pre-installed movements of behaviors for the robot. For each of the robot moods, a selection was made of suitable pre-installed movements. The happy robot had the most expressive movements, making great use of its arms and nodding strongly[17]. The neutral robot would be gently swaying its arms and make gestures with them every now and then, but those were not as strong as those of the happy one. Next to that, the neutral robot was also programmed to look around, making eye contact with the participants[17]. And finally, for the sad robot, it was the objective to minimize movement and give Pepper a sad posture. This was achieved by using the same built-in movement that was used for the gentle swaying of the neutral robot. This behavior included the eye contact movement of the head, so the head movement had to be disabled using the settings of the dialog box. Next to shutting off the eye contact behavior, Pepper was programmed to look down at all times within these same settings. The sad posture was finalized by adjusting the hinge at the hip and the shoulders[19].

The robot's eye colors were changed using the eye LEDs to represent the three different moods: yellow was used for happy, white for neutral, and light blue for the sad robot[14].

A video was made to visually show the three different emotional behavior's of Pepper.

Laptops

In the full study, four laptops were used. At the start of the experiment, three laptops were used to hand to the participant for filling in the demographics LimeSurvey. During the experiment, one laptop was used to direct Pepper to tell the different stories with the different emotions. This was done from the control room. Two other researchers were present in the room with the participants and Pepper to assist if necessary and take notes on their laptop, so two other laptops were used there. Moreover, during the interviews, the researcher could choose to keep their laptop with them for taking notes or recording. If chosen not to, the researcher used a mobile phone to record.

LimeSurvey for demographics

The demographics survey that participants were asked to fill in consisted of the following questions:

- What is your age in years?

- What is your gender?

- Male

- Female

- Non-binary

- Other

- Do not want to say

- What study program are you enrolled in currently?

- In general, what do you think about robots?

- Did you have contact with a robot before? Where and when?

These last two questions were based on an article by Horstmann & Krämer[20], which focused on the expectations that people have with robots and their expectations when confronted with other social robots concepts.

Stories told by the robot

The positive and negative stories that the robot told are fictional stories about polar bears, inspired by the study Bishop et al., 2019[11]. The content of the stories is based on non-fictional internet sources and rewritten to best fit our purpose. It was decided to keep the stories fictional and about animals rather than humans, because of the lower risk of doing emotional damage to the participants associated with elicited feelings based on personal circumstances.

The positive story is and adaptation of Cole (2021)[21] and shown below:

“When Artic gold miners were working on their base, they were greeted by a surprising guest, a young lost polar bear cub. It did not take long for her to melt the hearts of the miners. As the orphaned cub grew to trust the men, the furry guest soon felt like a friend to the workers on their remote working grounds. Even more surprising, the lovely cub loved to hand out bear hugs. Over the many months that followed, the miners and the cub would create a true friendship. The new furry friend was even named Archie after one of the researcher’s children. When the contract of the gold miners came to an end, the polar bear cub would not leave their side, so the miners decided to arrange a deal with a sanctuary in Moscow, where the polar bear cub would be able to live a happy life in a place where its new-found friends would come to visit every day.”

The negative story is an adaptation of Alexander (n.d.)[22] and shown below:

"While shooting a nature documentary on the Arctic Ocean Island chain of Svalbard, researchers encountered a polar bear family of a mother and two cubs. During the mother's increasingly desperate search for scarce food, the starving family was forced to use precious energy swimming between rocky islands due to melting sea ice. This mother and her cubs should have been hunting on the ice, even broken ice. But they were in water that was open for as far as the eye could see. The weaker cub labours trying to keep up and the cub strained to pull itself ashore and then struggled up the rock face. The exhausted cub panicked after losing sight of its mother and its screaming could be heard from across the water. That's the reality of the world they live in today. To see this family with the cub, struggling due to no fault of their own is extremely heart breaking.”

Interview questions

Two semi-structured interviews were held per participant, one after the first three conditions, in which the story is the same, and one after the second three conditions. These interviews were practically the same, except for one extra question (question 7) in the second interview (see below). The interview questions 1-8 were mandatory and questions a-q were optional to use as probing questions. Researchers were free to use these probing questions or use new questions to get a deeper understanding of the participant's opinion during the interview. The interviews also included a short explanation beforehand. The interview guide was printed for each interview with additional space for taking notes.

The interview questions were largely based on literature research. They were divided into three different categories: attitude, trust and comfort. Overall, these three categories should give insight into the general acceptance of robots by students[23][24][25]. Firstly, a manipulation check was done to make sure the participants had a correct impression of the story and the emotion the robot was supposed to convey. These were followed by questions about the attitude, focusing on the general impression that the students had of the robot, their likes and dislikes towards the robot, and their general preference for a specific robot emotion. These questions were mainly based on the research of Wu et al (2014)[26] and Del Valle-Canencia (2022)[27]. The questions about the trustworthiness of the different emotional states of the robot are based on Jung et al. (2021)[28] and Madsen and Gregor (2000)[29]. The comfort-category focused mainly on how comfortable the participants felt with the robot. These questions were based on research (Erken, 2022)[30]. Lastly, the participants were asked whether they think Pepper would be suitable to use on campus and for which tasks. The complete interview, including the introduction, can be seen below: You have now watched three iterations of the robot telling a story. During each iteration the robot had a different emotional state. We will now ask you some questions about the experience you had with the robot. We would like to emphasize that there are no right or wrong answers. If there is a question that you would not like to answer, we will skip it.

- What was your impression of the story that you heard?

- a. Briefly describe, in your own words, the emotions that you felt when listening to the three versions of the story?

- b. Which emotion did you think would best describe the story?

- How did you perceive the feelings that were expressed by the robot?

- c. How did the robot convey this feeling?

- d. Did the robot do something unexpected?

- What did you like/dislike about the robot during each of the three emotional states?

- e. What are concrete examples of this (dis)liking?

- f. How did these examples influence your feelings about the robot?

- g. What were the effects of the different emotional states of Pepper compared to each other?

- i. What was the most noticeable difference?

- Which of the three robot interactions do you prefer?

- h. Why do you prefer this emotional state of the robot?

- i. If sad/happy chosen, did you think the emotion had added value compared?

- j. If neutral chosen, why did you not prefer the expression of the matching emotion?

- Which emotional state did you find the most trustworthy? And which one the least trustworthy?

- k. Why was this emotional state the most/least trustworthy?

- l. What did the robot do to cause your level of trust?

- m. What did the other emotional states do to be less trustworthy?

- Which of the three emotional states of the robot made you feel the most comfortable in the interaction?

- n. Why did this emotional state make you feel comfortable?

- o. What effect did the other emotional state have?

- Do you think Pepper would be suitable as a campus assistant robot and why (not)?

- p. If not, in what setting would you think it would be suitable to use Pepper?

- q. What tasks do you think Pepper could do on campus?

- Are there any other remarks that you would like to leave, that were not touched upon during the interview, but that you feel are important?

Procedure

When participants entered the experiment room, they were instructed to sit down on one of the five chairs in front of the robot Pepper (see Figure 2). Each chair had a similar distance to the robot of about 1 meter. The robot Pepper was already moving rather calmly to get participants used to the robot movements. This was especially important since some participants were not yet familiar with Pepper.

The participants started with a short introduction of the study, as can also be seen in the research protocol linked below, and the request to read and sign the consent form and continue with filling in a demographic survey on LimeSurvey. There were two sessions with each five participants. First, the participants listened to Pepper, who told the group a story about a polar bear, either a positive or a negative one (see Table 4 and 5 for exact condition-order per session). Pepper told this story three times, each time with a different emotion, which could be ‘happy', ‘sad’ or ‘neutral’. The time that these three iterations took was approximately 6 minutes. When Pepper was finished, the five participants were asked to each follow one of the researchers into an interview room. These one-on-one interviews were held simultaneously and lasted approximately 10 minutes. After completing the interview, the participants went back to the room where they started and listened again to a story about a polar bear. If they had already listened to the positive story, they now proceeded to the negative one and vice versa. After Pepper had finished this story, the same interview was held under the same circumstances. After completion of the interview, there was a short debriefing. The total the experiment lasted about 45-60 minutes.

| Round | story | Emotion 1 | Emotion 2 | Emotion 3 |

| 1 | Negative | Neutral | Sad | Happy |

| 2 | Positive | Neutral | Happy | Sad |

| Round | story | Emotion 1 | Emotion 2 | Emotion 3 |

| 1 | Positive | Neutral | Happy | Sad |

| 2 | Negative | Neutral | Sad | Happy |

An elaborate research protocol was also made, which explains more detailed what should be done during each part of the experiment.

Data analysis

The data analysis done in this research is a thematic analysis of the interviews. The interviews were audio-recorded and from the recordings a transcript was made using Descript. As a first step to the data analysis process, the raw transcripts were cleaned. This includes removing nonsense words, like “uhm” and “nou” or any other forms of stop words. The speakers in the transcript were then also labelled with “interviewer” and “participant X” to make the data analysis easier. After the raw data was cleaned, the experimenters were instructed to become familiar with the transcripts, after which they could start the initial coding stage. This means highlighting important answers and phrases that could help answer the research question. These highlighted texts were then coded using a short label. All the above steps were done by the experimenters individually for their own interviews.

The next step would be combining codes and refining them. This was done during a group meeting where all the codes were carefully examined and combined to form one list of codes. After this, the experimenters recoded their own interview with this list of codes and another experimenter checked the recoded transcript. Any uncertainties or discussions on coding that arose were discussed in the next group meeting. In this meeting, some codes were added, removed or adjusted and the final list of codes was completed. The codes in this final list are divided into themes that can be used to eventually answer the research question. After this meeting, the interviews were again recoded using the final list of codes and the results were compiled from the final coding. The fully codes transcripts were all combined in one file.

Results

Results of thematic analysis

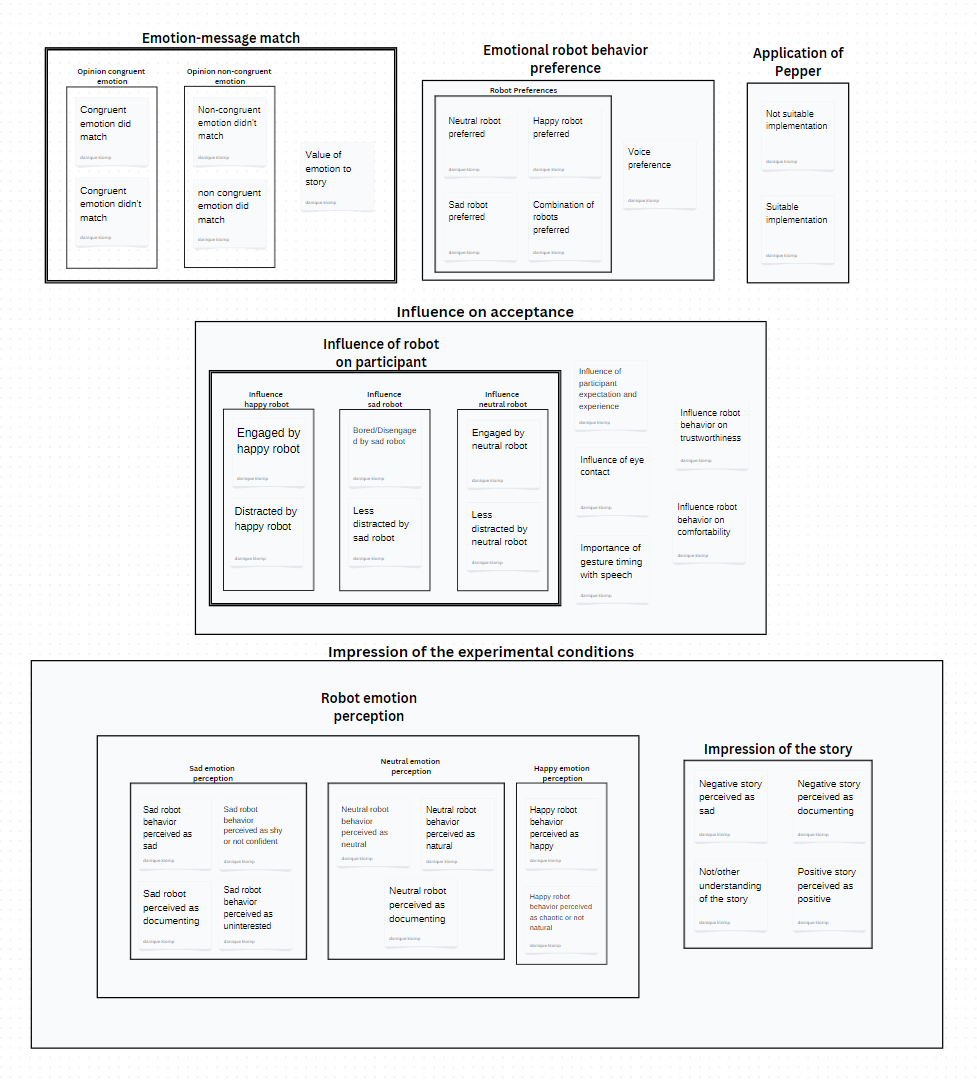

An overview of the final codes and themes as emerged from the thematic analysis is shown in Figure 3 and an explanation for each code and theme is provided in Table 6.

| Overarching themes | Themes | Subthemes | Code | Explanation |

| Impression of the experimental conditions | Impression of story | This theme includes all the impressions from the participants of the stories told by the robot | ||

| Negative story perceived as sad | Negative story is perceived as sad or described in a sad way. Sad undertones included. | |||

| Negative story perceived as documenting | Negative story is perceived as documenting. This is a neutral factual way of talking about the story. | |||

| Not/other understanding of the story | Difficulty understanding/ following the story, influence on later perceptions or preferences | |||

| Positive story perceived as positive | Positive story is perceived as happy, funny, entertaining, enthusiastic, etc. The tone is positive. | |||

| Robot emotion perception | This theme includes all the perceptions and opinions on the robot's emotional behavior. | |||

| Happy emotion perception | Happy robot behavior perceived as happy | All behavior of the happy robot that was perceived as happy, entertaining, funny, excited, energetic, etc. | ||

| Happy robot behavior perceived as chaotic or not natural | All behavior of the happy robot that was perceived as too chaotic or random in movements, sometimes leading to not being natural. | |||

| Sad emotion perception | Sad robot behavior perceived as sad | The behavior of the sad robot was perceived as sad. | ||

| Sad robot behavior perceived as shy or not confident | All behavior of the sad robot that was perceived as the robot feeling shy, hesitant, uncomfortable, not confident, etc. | |||

| Sad robot behavior perceived as uninterested | All behavior of the sad robot that was perceived as the robot not being interested in what it was telling. | |||

| Sad robot behavior perceived as documenting | All behavior of the sad robot that was perceived as the robot being serious or telling a story in a documenting way. | |||

| Neutral emotion perception | Neutral robot behavior perceived as neutral | All behavior of the neutral robot that is perceived as not having a specific emotion | ||

| Neutral robot behavior perceived as natural | All behavior of the neutral robot that is perceived as natural human-like behavior. | |||

| Neutral robot behavior perceived as documenting | All behavior of the neutral robot that was perceived as the robot being serious or telling a story in a documenting way. | |||

| Influence on acceptance | Influence of robot on participant | This theme includes all the influences that participants experienced with direct regard to the robot's emotional behavior. | ||

| Influence happy robot | Engaged by happy robot | The participant felt inspired, engaged or encouraged to listen to the story and pay attention by the happy robot. | ||

| Distracted by happy robot | The participant felt distracted by the happy robot movements and noise of movements | |||

| Influence sad robot | Bored/Disengaged by sad robot | The sad robot was perceived as boring and participants were disengaged by the robot. | ||

| Less distracted by sad robot | The sad robot was perceived as less distracting or allowing for more focus on the message than the other robots

| |||

| Influence neutral robot | Engaged by neutral robot | The participant felt inspired, engaged or encouraged to listen to the story and pay attention by the neutral robot. | ||

| Less distracted by neutral robot | The neutral robot was perceived as less distracting or allowing for more focus on the message than the other robots. | |||

| Influence of participant expectation and experience | Participant remarks on how their expectations of the experiment and experience with the robot Pepper influenced their perception | |||

| Influence robot behavior on trustworthiness | The reasoning behind why a certain robot was/wasn’t trustworthy based on its behavior. | |||

| Influence robot behavior on comfortability | The reasoning behind why a certain robot did make the participant feel (un)comfortable based on its behavior. | |||

| Importance eye contact | Participant adresses the effect of the robot (not) making eye contact. | |||

| Importance of gesture timing with speech | Participant adresses that gestures did not match with speech and what effect this had on them. | |||

| Emotion-message match | These are the codes that look at the match between the emotional behaviors displayed by the robots and the message that is told by the robot and how important emotions are in storytelling. | |||

| Opinion congruent emotion | Congruent emotion did match | The robot behavior that was expected to match did match the story that the robot told. | ||

| Congruent emotion didn't match | The robot behavior that was expected to match the story did not match according to participants. | |||

| Opinion non-congruent emotion | Non-congruent emotion didn't match | The robot behavior did not match the story that the robot told. | ||

| Non-congruent emotion did match | The robot behavior that was not expected to match the story did match according to participants, though this seemed due to numerous different reasons such as not understanding the story. | |||

| Value of emotion to story | Discusses if the participant felt that the emotion had added value to the story-telling or not. | |||

| Emotional robot behavior preference | These are all the preferences that the participants expressed regarding the robot's emotional behavior. | |||

| Robot preferences | Neutral robot preferred | Participant indicates a preference the neutral robot. | ||

| Happy robot preferred | Participant indicates a preference the happy robot. | |||

| Sad robot preferred | Participant indicates a preference for the sad robot. | |||

| Combination of robots preferred | The participant preferred the robot with a combination or switch between multiple emotional states. | |||

| Voice preference | Discusses what the participant likes/disliked about the voice of the robot | |||

| Application of Pepper | This theme looks at the real-life applications of pepper and whether the robot would be suitable as an application. | |||

| Not suitable implementation | The pepper robot is not suitable or needs adjustments before it is suitable in real life. | |||

| Suitable implementation | The pepper robot would be suitable for specific roles (navigation, guidance, administration tasks etc.) as is. |

Impression of experimental conditions

The overarching theme ‘Impression of experimental conditions’ arose from questions regarding how the participant perceived the emotional story and the emotional robot behaviour. These answers were gathered to do a manipulation check on the experimental conditions, thus checking if these are perceived as intended.

Impression of story

For the positive story that was told by Pepper, it was found that nearly all participants perceived it as a positive story and described it as either happy, funny, entertaining or any other positive adjective, such as shown in these quotes: “It was a very cute story. A nice story.” (Participant 013 – PS, [00:00:39]), “It was a happy story just because, it had a happy ending.” (Participant 014 – PS, [00:01:06]) and “I thought it was a funny story.” (Participant 023 – PS, [00:00:33]).

The negative story on the other hand, was sometimes perceived as sad and sometimes as more documenting, factual and with no clear emotional message. The following quotes illustrates this: “The general tone of the story was a bit sad, a bit anxious.” (Participant 012 – NS, [00:00:45]) and “The story sounded like a documentary.” (Participant 022 – NS, [00:01:09]).

Moreover, not all participants understood the story as intended or at all and this seemed to have influenced their attitude towards the emotional states of the robot. Some participants indicated that they found the story hard to follow due to difficult words or that they did not know what to expect at the beginning of the experiment and were a bit distracted.

Robot emotion perception

Additionally, the participants were asked which emotion they would assign to each of the robot's three emotional states. For the robot behavior that was intended as happy, most participants identified this as happy, enthusiastic, or another similar positive adjective. However, the happy robot behavior was also often perceived as chaotic, random or programmed in its movements, sometimes leading to their behaviour seen as not natural. This could also be linked to the fact that many participants noticed that the timing of the gestures did not fit with the context of the story at that point. This was mostly noticeable in the happy robot, but participants also made this comment about the other robot conditions. Examples are given in the following quotes: “It seemed just very excited and maybe happy to tell the story” (Participant 024 – PS, [00:02:02]), “The more energetic one is just too much for me. I think the gestures don't make any sense. It's just really random and really chaotic.” (Participant 014 – PS, [00:07:32]) and “I also felt that the arm movements again did just not at all correlate with what a person presenting the same story would do. Because it just was too much." (Participant 012 – PS, [00:02:01]).

Concerning the sad robot behaviour, the opinions of participants on how the undertone of the behaviour was perceived varied more, from sad to shy to uninterested to more seriously documenting the story. The following quotes again illustrate the different opinions of the participants: "The robot was a bit more sad and more serious in their voice” (Participant 021 – NS, [00:02:18]) and “It was more like it was a person presenting who was afraid to present." (Participant 012 – NS, [00:03:15]).

Finally, the neutral robot behavior was successfully interpreted as neutral in emotion by most participants, and additionally as more seriously documenting the story. The neutral robot was often also seen as the most natural and human-like behaving robot. Some examples of participants illustrating this: “The first one wasn't really an emotion, but more informative or something.” (Participant 022 – NS, [00:01:09]) and "It felt more human like.” (Participant 024 – PS, [00:01:28]).

Influence on acceptance

The next overarching theme ‘Influence on acceptance’ discussed various factors that participants experienced regarding the robot's behavior. This includes specific robot behavior characteristics that influenced how engaged participants felt to listen to the story, such as eye contact and timing of gestures, but also behavior that was noted as influencing comfortability and trustworthiness. These factors were often mentioned in relation to how engaged participants felt and a how natural the robot behavior was perceived.

Influence of robot on participant

Continuing with the subtheme ‘Influence of robot on participant’, the different emotional robot behaviors had different effects on the participants in term of their focus on the story. Almost all participants indicated multiple times that the happy robot engaged them to listen, but that the extreme movements and associated noise of the actuators distracted them a lot: “It tried to actively engage listeners” (Participant 012 – PS, [00:02:01]) and “It became distracting, I thought. But mostly also because the movement of the robot makes noise, and I'm going to pay more attention to that.” (Participant 022 – PS, [00:01:47]).

The sad robot seemed to strongly have the opposite effect, namely that participants were less distracted by the robot, but sometimes even to the extent that they felt disengaged to listen or even bored, as demonstrated here: “There was too little motion and hand gestures. And I think for a long period of time, that would be too boring to listen to. But, the benefit from that, is that you are only focused on the story itself, not on the robot movement” (Participant 014 – NS, [00:03:40]).

The neutral robot also distracted the participants less, but a part of the participant still felt engaged to pay attention to the story: “It's not as distracting as the other ones and the most being focused on the story.” (Participant 021 – NS, [00:05:09]). These factors clearly influenced the opinion of the participant towards each robot's emotional states and ultimately may have determined their preference for a certain robot emotion for the story that was told.

Eye contact, timing of gestures, trust and comfortability

For example, for the low engagement level of the sad robot, many participants gave their need for eye contact as an explanation. They felt less connected and engaged with the robot since it only looked downwards. Many participants also noted the incongruence between the gestures and speech as a reason for their low engagement with the robot: “Maybe when the story is building up, you can try to see if one gesture fits better with that part of the story. So you can really connect to it because you have a beginning point and end point of it” (Participant 011 – NS, [00:03:32]).

From time to time, these factors were linked to the robot's trustworthiness and participant's comfortability during interacting with the robot. There were also other reasons for a difference in trusting or feeling comfortable around a certain robot behaviour. For example, participants mentioned that they felt more comfort and trust with the happy robot during the positive story since the gestures fitted: “Now I would say the happy one the most trustworthy, because it fits the story well. [...] I noticed the gestures is less heavy than in the previous story. Maybe because it blended so well.” (Participant 011 – PS, [00:05:35]). However, when a participant felt that the emotion did not match or was unpredictable, it felt less comfortable with the happy robot: “The active [happy] robot makes it maybe a bit uncomfortable because it was too happy in combination with the story that was told” (Participant 021 – NS, [00:05:40]) and “I just felt like it was trying way too hard. [...] He basically just stood there, I know. But it felt a bit unpredictable or something.” (Participant 023 – PS, [00:08:23]).

The lack of eye contact from the sad robot was often mentioned as a reason for a low level of trust and/or comfort: “And the scary one looked only down at you with those eyes. So it lacked a bit of motion. So that just affected their comfort.” (Participant 011 – PS, [00:07:25]). Some participants also found the sad robot to be less trustworthy because they perceived it as shy. “Well, the third one [sad robot] [...] was not trustworthy as it was telling the story as if it didn't want to tell you the story because it was [...] shy and drawn back. The second one [happy robot], you could call it trustworthy [...]. It was actively trying to convince the listeners that that story was of a certain emotion and maybe it overdid that.” (Participant 012 – PS, [00:08:41]).

Most often, the participants saw the neutral robot as the most comfortable or trustworthy, for example since it was the most natural: “Because if it's natural, then it's trustworthy.” (Participant 013 – PS, [00:06:12]). Also, the neutral robot showed more eye-contact, which many participants found to be more trustworthy: “Because the robot was really looking at us. And I think you would do that when you're confident about your own story and want to be trusted.” (Participant 021 – PS, [00:05:42]).

Moreover, for some participants, their expectations of the experiment had notable influence on what they noticed during the conditions or the extent to which they had previous experience with the robot determined a strong overall attitude towards the robot. “Because this was totally new, I didn't know what to expect. that's also maybe an aspect that maybe influences my thoughts upon the robot itself. Just because when you get the story from the robot, then a lot of things pop into my mind, [...] so you're really distracted by many things. And then, the second and the third robots [happy and sad robot], you're more like at rest [...]. So that may cause a different outputs from people, when they encounter to those robots for the first time.” (Participant 014 – NS, [00:07:53]).

Emotion-message match

Participants also noted a congruence or incongruence between the emotional state of the robot and the story that it told. Most often, participants indicated a match between the intended congruent emotional state and the story, or a mismatch between the intended incongruent emotional state and the story. The following quotes exemplify these occasions: “Its emotions, [...] the sad eyes, matched better with the story that was being told.” (Participant 012 – NS, [00:05:35]) and “This story was of course happy and then, more happy emotions would also be more realistic for the audience” (Participant 014 – PS, [00:01:57]).

However, during multiple interviews, participants had another understanding of the emotional state or story and therefore did not find it fitting, or they understood what emotional state was congruent, but they did not feel that it fitted well due to other disliked prominent behavior of the robot. As a result, most of these participants preferred the neutral robot, though some of them felt that the intended non-congruent emotion matched better. This is mentioned in the next quotes: “I would say the energetic one, because that would match the story. But for some reason, if I would have to trust the robot itself, then I would say the medium one [neutral robot], just because the over energetic one is... then I would get the feeling that they want to convince me” (Participant 014 – PS, [00:05:59]) and “The [negative] story sounded more like a documentary. I thought the first one [neutral robot] was better for a documentary. The second one [sad robot] was too sad. And the third one [happy robot] was too enthusiastic.” (Participant 022 – NS, [00:03:36]).

During this, it was occasionally also discussed if participants felt like the emotional states of the robot added value to the storytelling or not. When the neutral or non-congruent emotion was preferred, participants frequently indicated that the emotion had no added value, while this was the other way around for congruent emotion preferences. For example, one of the participants preferred the happy robot during the positive story, and they mentioned that this happy emotion did give the story more value: “I could feel this joy of the people there, that could kind of adopt a polar bear, and a polar bear that could see his friends.” (Participant 011 – PS, [00:05:09]). However, there were also participants that did not want any emotion in the storytelling: “I don't think so. I think when you're trying to convey a story, you just want to have the story told. And you want the story to be the main purpose of telling.” (Participant 015 – PS, [00:04:30]).

Emotional robot behavior preference

Taking all this into account, theme ‘Emotional robot behavior preference’ includes which robot each participant named as an overall preferred, most trustworthy and most comfortable robot's emotional state for each story. The results from this can also be seen in Table 7, which is discussed later.

Additionally, some participants also discussed specifically which version(s) of the voices they liked or disliked and why. For example, “Now the last one [voice of happy robot] was definitely more engaging, but sometimes it was a bit loud, even though it didn't really fit the story. The first one [voice of neutral robot] was too neutral, so the intonations were on one line, so maybe a combination? Just having more intonation, I would say.” (Participant 011 – NS, [00:07:32]). Sometimes, the participants also found the voice of the sad robot to be inaudible: “For the second one [sad robot], it was [...] less audible than the other, than the first one [neutral robot].” (Participant 015 – NS, [00:00:42]).

Application of Pepper

Finally, the theme ‘Application of Pepper’ encompasses the responses that participants had to the question of for which application Pepper would be suitable. The interviews showed that most participants could see Pepper being used in real life, but mostly for short, easy tasks, such as pointing people in the right direction on campus or giving some basic information: “I can already see Pepper standing in front of the university and leading the way around. Answering questions like where do you have to go, and then the road.” (Participant 013 – PS, [00:07:59]). However, they also noted possible limitations in Pepper’s implementations. For example, they do not believe that Pepper could have deeper conversations with people, so it would not be suitable for more difficult campus related tasks such as teaching or more serious or emotional messages. Some also noted that they don’t see the usefulness of Pepper, since humans will usually be able to do a task better. For example, “For storytelling, making people aware of really serious things, then I would think maybe less suitable because I don't really see the seriousness or maybe I don't really feel like I should listen to the robot. I think a real human would make more impact.” (Participant 021 – NS, [00:06:51]) and “There is already this reception down below as well, where you can ask questions, where there's always a person, which will still be better than most robots.” (Participant 015 – PS, [00:06:25]). However, most participants were more positive about Pepper, although improvements would first have to be made.

Participants preferences for emotional states of the robot

As introduced before, Table 7 shows the preferences of participants in which emotional state they preferred overall, which was more trustworthy and which they found most comfortable. The table includes the total scores that the robot received from all the participants. When a participant preferred a combination of robots, the robot received a fraction of a full point.

From Table 7 it can been seen that the neutral robot was scored the highest by the participants in all three categories, for both the positive and the negatives story. From the more expressive robots, the happy robot received the highest scores in all three the conditions again for both the positive and the negative story, while the sad robot received only a small fraction of the scores.

In addition to the stand-alone preference of the participants, it was also examined whether participants preferred the same robot or the same combination of robots in all three the categories. The results of this can be found in Table 8 and 9. In summary, seven out of ten participants preferred the same robot in all three categories. Most participants choose the neutral robot in all three categories, but sometimes a combination with the neutral and happy robot was preferred. The negative story had slightly more mixed results, these showed only three participants that preferred the same robot in all three the categories. Again, most participants preferred the neutral robot in all three categories, while some preferred the happy robot.

| General | ||

| Positive story | Negative story | |

| Happy robot | 2 | 2⅔ |

| Sad robot | 0 | 2⅔ |

| Neutral robot | 8 | 4⅔ |

| Trust | ||

| Positive story | Negative story | |

| Happy robot | 3 | 1 ½ |

| Sad robot | 0 | ½ |

| Neutral robot | 7 | 8 |

| Comfort | ||

| Positive story | Negative story | |

| Happy robot | 2 ½ | 2 ½ |

| Sad robot | 1 | ½ |

| Neutral robot | 6 ½ | 7 |

| Participant | General | Trust | Comfort | Conclusion |

| 1 | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral | All three the same |

| 2 | Neutral | Happy | Happy | Trust + Comfort the same |

| 3 | Combination happy and neutral | Combination happy and neutral | Neutral | General + Trust the same |

| 4 | Happy | Happy | Happy | All three the same |

| 5 | Neutral | Neutral | Sad | General + Trust the same |

| 6 | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral | all three the same |

| 7 | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral | all three the same |

| 8 | Combination happy and neutral | Combination happy and neutral | Combination happy and neutral | all three the same |

| 9 | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral | all three the same |

| 10 | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral | all three the same |

| Participant | General | Trust | Comfort | Conclusion |

| 1 | Combination happy and neutral | Neutral | Combination happy and neutral | General + Comfort the same |

| 2 | Combination sad and neutral | Neutral | Neutral | Trust + Comfort the same |

| 3 | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral | All three the same |

| 4 | Combination happy and neutral | Neutral | Combination happy and neutral | General + Comfort the same |

| 5 | Combination of all three the robots | Combination happy and neutral | Combination happy and neutral | Trust + Comfort the same |

| 6 | Sad | Neutral | Combination sad and neutral | All three different |

| 7 | Happy | Happy | Happy | All three the same |

| 8 | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral | All three the same |

| 9 | Combination sad and happy | Combination sad and neutral | Neutral | All three different |

| 10 | Combination of all three the robots | Neutral | Neutral | Trust + Comfort the same |

| 10 | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral | All three the same |

Discussion

Main findings

When looking back at the research question, “To what extent does a match between the displayed emotion of a social robot and the content of the robot’s spoken message influence the acceptance of this robot?”, in combination with the results, it becomes clear that most participants were not that influenced by the match of emotion to story. As shown in Table 7, the neutral robot state was clearly most preferred for each story and each aspect of acceptance. Therefore, our pre-research expectation that the congruent emotion would be most preferred, was falsified. Taking into account the in-depth reasoning of participants during the interview, this preference did not always depend on how suitable the robot's emotional state was for the specific story. Rather, in most cases, participants preferences stemmed from disliking the happy and sad emotional robot state and finding the neutral behavior the most natural for human-like behavior or a good in-between the other more extreme states.

Moreover, it was expected that the importance of congruent emotion displaying would be more apparent for the negative story than the negative story. This would mean that there is a clearer preference for the congruent emotion and less for the incongruent emotion when comparing to the positive story. However, Table 7 shows inconsistent results. Only for the overall preference, the congruent emotion is more preferred for the negative story than for the positive story. For all other cases, the congruent emotion is more preferred and the incongruent emotion less preferred for the positive story than for the negative story. This may indicate that congruent emotion displaying is more important for positive messages. The higher level of trust in the happy robot could also be explained by positive, in comparison to negative, emotional expression leading to higher anthropomorphic trust in social robots[31].

Comparing these results to other similar research, such as the study of Van Otterdijk et al. (2021)[14], shows contrasting results. Van Otterdijk and colleagues found no clear preference among different robot behaviors, where our study found a prominent preference for the neutral robot behavior. Moreover, they found that for delivering a negative message, the congruent sad robot behavior was significantly more preferred. This is again in contrast with our results whereas the importance congruence was more present for the positive story. However, it is important to note a clear difference in robot behavior, namely that in the study of Van Otterdijk et al., Pepper was approaching participants, whilst our Pepper was standing still. As the authors also explain, the surprising results could also be caused by the emotional robot behavior not being experienced as intended. For their study, the neutral and happy behavior were perceived as quite similar, though in our study participants indicated a clear difference. Moreover, they also discussed that in the context of elderly in a care center, bringing sad news may be more triggering. Appel et al. (2021)[32] conducted a similar study with the robot Reeti. However, differences are that only facial expressions were manipulated, and the robot told the stories from first-person perspective. The found that congruent emotion displaying positively affected transportation in the story world and led to more positive evaluations of the robot. The differences in results can again be explained by differences in robot behavior or the robot’s anthropomorphism, but also the extent to which the stories and emotions were interpreted as intended.

Though the results do not give a clear answer on the research questions, the in-depth analysis of the interview resulted in some theoretical implications and practical recommendations for programming emotional behavior with Pepper. The results showed varying opinions about suitable implementations for the Pepper robot as campus assistant, such as for guiding or providing general information, but no tasks that deal with emotions or responsibility and occasionally still a preference for humans performing the task. This indicates that the targeted user group is not yet very acceptable of using Pepper based on the interaction during the experiment and previous attitude, especially when it comes to its emotion displaying. The participants’ dislikes of the emotions states probably influenced this. Consequently, improvements must be made on how Pepper displayed emotions to change the users’ attitude towards Pepper engaging in tasks involving emotions. First of all, the happy robot behavior was very often perceived as way too extreme in its movements, while the sad robot was noted as moving too little, and the neutral robot was seen as the most natural. The emotional robot behavior used in this study and the differences between states were too extreme. The participants clearly indicated that they prefer more subtle changes and natural movements. Therefore, we recommend for practical implications that the neutral robot behavior should be used as a basis from which only small adjustments should be made to create robot behavior for other emotions. These adjustments should be carefully determined by investigating how humans naturally convey these emotions while telling a story.

Limitations

In this study, despite careful planning and execution, several constraints emerged that warrant acknowledgment. Understanding these limitations is crucial for contextualizing the results and guiding future research. The following section outlines the key limitations that were encountered during the experimental process, shedding light on areas for refinement and further investigation.

There were a few cases in which the participant misunderstood a story. The stories serve as crucial components in determining participants' preferences for congruent versus incongruent scenarios. When participants misunderstand the narrative, their responses may not accurately reflect their true preferences or emotional reactions[33]. In addition to that, the negative story was sometimes perceived as a newspaper story. This was because it lacked personal emotional value, as the decision was made to lower the risk of participants experiencing emotional damage due to the storytelling. The study by Appel et al (2021)[32] made use of a story that was personal to the robot itself. If this was done during this particular experiment, emotional value would have been added properly and possibly could have prevented the sense of detachment from the emotional essence of the story.

Due to the duration of the course and the availability of Pepper, there was limited time to get familiar with the robot in combination with the Choregraphe software. This resulted in the choice of using the pre-installed Choregraphe behaviors. Consequently, there was not enough time to explore methods to make the robot's expressions more nuanced and less exaggerated, as some participants perceived them to be, particularly regarding the portrayal of happiness. Some of the participants also stated that they would have preferred a different emotion if the other one was not as extreme.

For feasibility reasons, the participants were all exposed to the same order of emotions for each of the stories. Whether they heard that in combination with the positive or negative story first depended on which iteration of the experiment they were participating in. Considering the peak-end rule, the predetermined mood sequence could have impacted the participants’ overall experience with Pepper. If the participant felt a positive or negative emotional peak near the end of the experiment, they might have attributed that feeling towards the entire experiment, regardless of how they, for example, felt for the first mood iteration. Thus, the sequence of mood exposure could have influenced participants' hindsight evaluations[34].

As the researchers on this project were not very experienced with interviewing, it has occurred that the interviewer could have asked for more explanation when they didn't. This resulted in missing out on possible relevant information for the study and having a possible, less deeper understanding of the results.

The last limitation was the limited screening that was done on participants before they were invited to the experiment. As the experiment relied on the ability of participants to pick up detailed emotional ques, some participants might have been better suited than other participants. Some conditions can have an impact on the perception of emotions and the interpretation of these emotions, like autism can have. As the participants were not specifically asked whether they had autism or any other condition that could have an impact on emotional perception, it might have had an impact on the misunderstanding of the emotion[35].

Recommendations for future research

Although the outcomes of this study deviated from expectations, they still shed valuable light on the field of Human-Robot Interaction (HRI), which holds significant relevance in contemporary society. Future research endeaveours can build upon these findings, refining them by addressing identified limitations. Primarily, it became evident that participants didn't always interpret the narrative as intended. To solve this, preliminary testing of the story and robot's emotional cues on non-participants could refine storylines before the main study. Additionally, participants noted difficulties comprehending the stories and maintaining focus during the robot's movements. Implementing measures such as pre-reading the story or initially having the robot deliver the story without movements could remove this issue. Moreover, Pepper's chest screen could be utilized to visually complement the story, enhancing engagement. These strategies aim to increase the likelihood that the stories have the intended effect, and therefore provide more valuable insights into emotion-message congruence.

One of the limitations that was mentioned was the choice for pre-installed Choregraphe behaviours. This lead to led to less the emotions being perceived as too exaggerated by many participants. In future research, it is recommended to spend to more time getting familiar with suitable programs and methods for programming Pepper. This could lead to more nuanced and subtle expressions that would be more appealing for the listeners. For this, also more research would have to be done into perceiving in human-robot interaction with Pepper, paying attention to what cues humans use to pick up on certain emotions of robots. Furthermore, by manually programming Pepper, more variation can be introduced in the intensities of the emotions during the story-telling, meaning the gestures and emotions as shown by Pepper correspond better to the context of the story that is told. Besides, a wider range of emotions could be used in future research, instead of only “happy”, “sad” and “neutral”, to gain more knowledge into the exact emotion that is preferred by participants, as they now often saw the “happy” and “sad” robot as too extreme. In real life, human emotions manifest across a nuanced spectrum. Emotions are very subtle and complex, since the perception of emotions is highly sensitive to context and personal factors. This implies the importance of considering this complexity in refining Pepper's emotional behavior[36].

In future investigations, it would be compelling to conduct a study with a more extensive participant pool. As depicted in Table 7, 8 and 9, while many participants exhibited consistent preferences for specific robots, outliers were observed — individuals with differing perceptions or opinions on robot emotions. Replicating the experiment on a broader scale as confirmatory research, with appropriate improvements, allows for statistical significance testing and could enhance the generalizability of results. Only then it is possible to validate whether the observed patterns hold true for a larger demographic.

In general, participants expressed a positive attitude toward having Pepper on campus for providing basic information like directions, although with some suggested adjustments. Further research is necessary to delve into the specifics of Pepper's role as a campus robot, including the type of information it can convey and the way it will do this (e.g., via voice, emotion display, movements). Since this study primarily examined students' general attitudes towards Pepper rather than its specific use as a campus robot, further research can aim for more targeted exploration in this regard.

Planning

Each week, there was a mentor meeting on Monday morning followed by a group meeting. Another group meeting was held on Thursday afternoon and by Sunday afternoon the wiki was updated for work done that week (weekly deliverable).

Week 1

- Introduction to the course and team

- Brainstorm to come up with ideas for the project and select one (inform course coordinator)

- Conduct literature review

- Specify problem statement, user group and requirements, objectives, approach, milestones, deliverables and planning for the project

Week 2

- Get confirmation for using a robot lab, and which robot

- Ask/get approval for conducting this study

- Create research proposal (methods section of research paper)

- If approval is already given, start creating survey, programming the robot or creating video of robot

Week 3

- If needed, discuss final study specifics, including planning the session for conducting the study

- If possible, finalize creating survey, programming the robot or creating video of robot

- Make consent form

- Start finding and informing participants

Week 4

- Final arrangements for study set-up (milestone 1)

- Try to start with conducting the study

Week 5

- Finish conducting the study (milestone 2)

Week 6

- Conduct data analysis

- Finalize methods section, such as including participant demographics and incorporate feedback

- If possible, start writing results, discussion and conclusion sections

Week 7

- Finalize writing results, discussion and conclusion sections and incorporate feedback, all required research paper sections are written (milestone 3)

- Prepare final presentation

Week 8

- Give final presentation (milestone 4)

- Finalize wiki (final deliverable)

- Fill in peer review form (final deliverable)

Individual effort per week

Week 1

| Name | Total Hours | Break-down |

| Danique Klomp | 13.5 | Intro lecture (2h), Group meeting (2h), Group meeting (2h), Literary search (4h), Writing summary LS (2h), Writing problem statement first draft (1,5h) |

| Liandra Disse | 13.5 | Intro lecture (2h), group meeting (2h), Searching and reading literature (4h), writing summary (2h), group meeting (2h), updating project and meeting planning (1,5h) |

| Emma Pagen | 12 | Intro lecture (2h), group meeting (2h), literary search (4h), writing a summary of the literature (2h), writing the approach for the project (1h), updating the wiki (1h) |

| Isha Rakhan | 11 | Intro lecture (2h), group meeting (2h), group meeting (2h), Collecting Literature and summarizing (5h) |

| Margit de Ruiter | 13 | Intro lecture (2h), group meeting (2h), literature research (4h), writing summary literature (3h) group meeting (2h) |

Week 2

| Name | Total Hours | Break-down |

| Danique Klomp | 16,5 | Tutormeeting (35min), groupmeeting 1(2.5h), groupmeeting 2 (3h), send/respond to mail (1h), literature interview protocols and summarize (3h), literature on interview questions (6.5h), |

| Liandra Disse | 12 | Tutormeeting (35min), groupmeeting (3h), write research proposal (3h), groupmeeting (3h), finalize research proposal and create consent form (2,5h) |

| Emma Pagen | 11,5 | Tutormeeting (35min), groupmeeting (3h), write research proposal (2h), groupmeeting (3h), finalize research proposal and create consent form (1,5h), updating wiki (1,5h) |

| Isha Rakhan | 10 | Research on programming (7h), groupmeeting (3h) |

| Margit de Ruiter | 11,5 | Tutormeeting (35min), groupmeeting (3h), read literature Pepper and summarize (3h), groupmeeting (3h), research comfort question interview (2h) |

Week 3

| Name | Total Hours | Break-down |

| Danique Klomp | 14 | Tutormeeting (35min), groupmeeting 1(3h), meeting Task (3h), preparation Thematic analysis & protocol (2h), mail and contact (1,5h), meeting Zoe (1h), group meeting (3h) |

| Liandra Disse | 12 | Tutormeeting (35min), groupmeeting 1(3h), meeting Task (3h), update (meeting) planning (1h), prepare meeting (1h), group meeting (3h), find participant (30min) |

| Emma Pagen | 12 | Tutormeeting (35min), groupmeeting 1(3h), finish ERB form (1h), create lime survey (1,5h), make an overview of the content sections of final wiki page (1h), group meeting 2 (3h), updating the wiki (2h) |

| Isha Rakhan | 12,5 | Tutormeeting (35min), groupmeeting 1(3h), meeting zoe (1h), group meeting (3h), programming (5h) |

| Margit de Ruiter | *was not present this week, but told the group in advance and had a good reason* |

Week 4

| Name | Total Hours | Break-down |

| Danique Klomp | 11,5 | Tutor meeting (35min), group meeting (3h), review interview questions (1h), finding participants (0.5h), mail and contact (1h), reading and reviewing wiki (1.5h), group meeting (4h), lab preparations (1h) |

| Liandra Disse | 11 | Prepare and catch-up after missed meeting due to being sick (1,5h), find participants (0.5h), planning (1h), group meeting (4h), set-up final report and write introduction (4h) |

| Emma Pagen | 13 | Tutormeeting (35min), group meeting (3h), adding interview literature (2h), find participants (0,5h), group meeting (4h), reviewing interview questions (1h), going over introduction (1h), updating wiki (1h) |

| Isha Rakhan | 11,5 | Tutormeeting (35min), group meeting (3h), research and implement AI voices (2h), documentation choices Pepper behavior (2h), group meeting (4h) |

| Margit de Ruiter | 11 | Tutormeeting (35min), group meeting (1h), find participants (0.5h), testing interview questions (1h), group meeting (4h), start writing methods (4h) |

Week 5

| Name | Total Hours | Break-down |

| Danique Klomp | 24,5 | Tutor meeting (30min), group meeting (experiment) (3h), transcribe first round of interviews (2h), familiarize with interviews (5h), highlight interviews (2h), group meeting (experiment) (3h), transcribe second round of interviews (2h), first round of coding (3h), refine and summarize codes (2h), prepare next meeting (1h), adjust participants in methods section (1h) |

| Liandra Disse | 21,5 | Tutor meeting (30min), group meeting (experiment) (3h), transcribe, familiarize and code first interviews (6h), incorporate feedback introduction (1h), group meeting (experiment) (3h), transcribe, familiarize, code second interviews and refine codes (7h), extend methods section (1h) |

| Emma Pagen | 20,5 | Tutor meeting (30min), group meeting (experiment) (3h), transcribe first round of experiments (3h), familiarize with interviews and coding of first interviews (4h), group meeting (experiment) (3h), transcribe second round of interviews (3h), familiarize with interviews and coding of second interviews (4h) |

| Isha Rakhan | 14,5 | Tutor meeting (30min), group meeting (experiment) (3h), group meeting (experiment) (3h) transcribing all of the interviews (4h), coding all of the interviews (4h) |

| Margit de Ruiter | 17 | Tutor meeting (30min), group meeting (experiment) (3h), transcribing all the interviews (7h), group meeting (experiment) (3h) coding all the interviews (3,5h) |

Week 6

| Name | Total Hours | Break-down |

| Danique Klomp | 18,5 | Tutor meeting (30 min), group meeting first round coding (3h), second round of recoding interviews (2h), check recoding of other interviewer (2h), look at comments/check recoding of other interviewer (1h), preparations meeting Thursday (2h), create preference count document for the group meeting (2,5h), group meeting (3h), recode and finalize transcripts (1,5h), work on thematic map and finalizing the themes/codes (1h), |

| Liandra Disse | 17,5 | Tutor meeting (30 min), group meeting first round coding (3h), second round of recoding interviews (2h), check recoding of other interviewer, go over comments on own interview and make suggestions for adjusting codes (4h), planning (1h), group meeting (3h), finalize transcripts (1h), start on results section and give feedback on methods (3h) |

| Emma Pagen | 16,5 | Tutor meeting (30 min), group meeting first round coding (3h), second round of coding (2h), check coding of other interviewer (2h), adjust own coding based on suggestions from other group member (1h), group meeting (3h), recoding after group meeting and finalize transcript (2h), finalize method (1h), update wiki (2h) |

| Isha Rakhan | 15 | Tutor meeting (30 min), group meeting first round coding (3h), second round of coding (2,5h), check coding of other interviewer (2h), check codes feedback other interviewer (1h), group meeting (2h), adjusting codes after group meeting (1h), working on the "Pepper" part of the report (3h) |

| Margit de Ruiter | 15 | Tutor meeting (30 min), group meeting first round coding (3h), second round of coding (2,5h), check coding of other interviewer (2,5h), check codes feedback other interviewer (2h) group meeting (2h), adjusting codes after group meeting (1h), check overview with themes and codes (1,5h) |